Midway through the regionally produced good-ol’-boy romp, Redneck Miller, the titular character – a hotshot DJ in some random Carolina municipality where "hotshot" bona fides are easy to come by provided one still has a functional tooth or two – breaks up the near rape of his mistress by a bunch of hoods looking to find their boss’s "stuff" (which they believe Miller has stolen). After chasing the thugs off, Miller tends to the badly frightened, but largely unmolested woman (they just smacked her around a little), who asks her white-trash knight what he would’ve done had her assailants held him at gunpoint while they ravished her. Miller’s smirking response?

Midway through the regionally produced good-ol’-boy romp, Redneck Miller, the titular character – a hotshot DJ in some random Carolina municipality where "hotshot" bona fides are easy to come by provided one still has a functional tooth or two – breaks up the near rape of his mistress by a bunch of hoods looking to find their boss’s "stuff" (which they believe Miller has stolen). After chasing the thugs off, Miller tends to the badly frightened, but largely unmolested woman (they just smacked her around a little), who asks her white-trash knight what he would’ve done had her assailants held him at gunpoint while they ravished her. Miller’s smirking response?

"You can take a lot of lovin’, baby, but I can only die once."

You know, the next time I spare a woman the psyche-shattering trauma of rape at the hands of three bumbling henchmen, I’m guessing my words of assuagement are going to be a little less cavalier.

But this is why I’ve been going to the New Beverly Cinema’s Los Angeles Grindhouse Festival as often as possible – to hear and see and, if the movie’s content is sufficiently rank, smell the kinds of things most movies are too timid to emanate. As you might’ve read by now, the festival’s offerings have been culled from the private celluloid stock of Quentin Tarantino, who intended the two-month-long program as a film geek complement to the theatrical release of Grindhouse. His selections have been killer. Aside from some well-known cult items (e.g. Rolling Thunder, The Town That Dreaded Sundown and The Lady in Red), I’ve seen a beat-for-beat urban remake of The 400 Blows that I didn’t even know existed called Johnny Tough (beat-for-beat, that is, until the deliriously perfect final freeze-frame), a kung-fu morality tale opportunistically titled The Chinese Mack, and the black-Vietnam-Vets-take-on-the-Klan epic, Brotherhood of Death. Tarantino also screened an obsession of mine called Bare Knuckles (don’t ask me to explain it, ‘cuz I wouldn’t know where to start), starring Robert Viharo as a badass bounty hunter chasing down a serial killer who kills broads with karate. It was better than Persona.

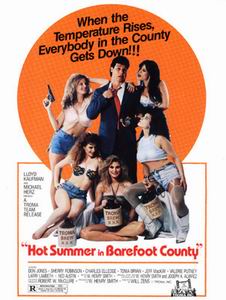

As invigorating as it is to see old favorites work an audience over the way they did in the 1970s, it’s just as enjoyable to hand over $7.00 at the New Bev’s ticket window for a double-feature of delights that no one’s written about before. How rare is that in the age of the internet, where cinephiles consumed by every conceivable predilection have spewed thousands of words over every out-of-print oddity to ever pass through a projector? But if you do a Google search for "Redneck Miller", you’ll pick up a measly ten pages of hits. "Hot Summer in Barefoot County"? Try fourteen pages.

I generally refrain from tracking down information on the Grindhouse Fest’s obscurities until after I’ve let them work me over like a cinderblock-fisted goon, so I was blissfully prone as I slouched down into a creaky seat at the New Beverly last Saturday for the Rednecksploitation double feature of Hot Summer in Barefoot County and Redneck Miller. (A third film had been added to the bill that evening, but a prior engagement nixed my hanging around for more ‘shine-fueled buffoonery. Also, I’d just put away Election and Triad Election at the American Cinematheque earlier in the day; pile on the liquor imbibed before and during the Grindhouse features, and my thoughts on that third movie would’ve been useless anyway.) As has been the case throughout the Festival’s run, the theater was packed with curiosity seekers like myself (and, I should add, CHUD‘s barrel-chested box office herald, Andre Deallmorte); spirits were high and enhanced, with everyone trusting that QT wouldn’t waste their Saturday night out at the movies with unwatchable dreck.

Two hours after the just plain awful Barefoot County, that trust was rewarded with the very special Redneck Miller. But, man, what a price to pay! Filmed in and around rural North Carolina, Barefoot County is the work of director Will Zens, a purveyor of regional exploitation whose best-known work is probably the MST3K-lampooned The Starfighters. The plot concerns Officer Jeff Wilson’s (Don Jones) undercover efforts to break up a moonshine racket in nearby Barefoot County, which is not so much terrorized as sporadically slightly pestered by the antics of incorrigible pussyhound Culley Joe (Jeff MacKay) and his weak-willed buddies, who basically cart Culley Joe to-and-from his various sexual conquests. Though Culley Joe can have his way at any given hour with Nadine, a waitress at the local diner (and daughter of the densely bearded sheriff played by Charles Elledge), he really wants to lay the pipe to the eldest daughter of the matronly hooch kingpin; but those plans are blown to shit when Not-So-Big Not-So-Bad Mama unsuspectingly takes in the interloping Wilson after he receives a down-home Barefoot County run-’em-off-the-road welcome from, who else?, Culley Joe.

(In case you’re wondering, my sporadic citing of character names is a product of faulty memory and a lack of a definitive cast list. Work with me, please.)

Wilson soon falls for the freckly, Sissy Spacek-looking prize of Mama’s litter (inexplicable, since her other two daughters are both more fetching and, it seems, more likely to put out), which is unfortunate since she’s also the brood’s hard-drivin’ ‘shine runner. This really cheeses off Culley Joe, but Zens and screenwriter W. Henry Smith can’t be bothered to construct a love triangle that might up the stakes a little. Instead, they honor the white trash tradition of having the corpulent Sheriff catch Joe in post-coital splendor with his daughter, thus necessitating a middle-of-the-night shotgun wedding.

Aside from Zens’s deficient direction, the real disappointment of Hot Summer in Barefoot County is the relative lack of tit; while there’s a flash of areola here and there, the bastard mostly skimps on nudity. Fortunately, John Clayton, the enlightened auteur of Redneck Miller, knows to deliver the goods, which is but one reason why his picture leaves Barefoot County sucking its dust.

Full of zaftig Carolina beauties and sudden outbursts of leisurely choreographed violence, Redneck Miller depicts the Schlitz-swilling heroics of a smooth-voiced DJ who’s framed for an offense against a local club owner he didn’t commit. That said club owner happens to be black seems to set the stage for a racially insensitive ode to outmoded southern justice, but Clayton and his screenwriters (including Barefoot County‘s W. Henry Smith!) are thankfully progressive enough to understand that not all African-Americans are treacherous. Hell, they even let Miller get himself a piece of black ass, which must’ve been a phenomenally dicey proposition back in the 1977.

Full of zaftig Carolina beauties and sudden outbursts of leisurely choreographed violence, Redneck Miller depicts the Schlitz-swilling heroics of a smooth-voiced DJ who’s framed for an offense against a local club owner he didn’t commit. That said club owner happens to be black seems to set the stage for a racially insensitive ode to outmoded southern justice, but Clayton and his screenwriters (including Barefoot County‘s W. Henry Smith!) are thankfully progressive enough to understand that not all African-Americans are treacherous. Hell, they even let Miller get himself a piece of black ass, which must’ve been a phenomenally dicey proposition back in the 1977.

Basically, the generous nudity, rampant Schlitz drinking and lackadaisical attitude toward rape are the highlights of Redneck Miller, and, when you’re doing a bit of drinking yourself, this is somehow more than enough fill out the ninety-minute run time. Actually, there might be a feminist statement smuggled into this lightly plotted gem (Miller’s in-house pussy threatens to leave him when he won’t keep his lovin’ exclusive), but I’ll leave that for someone else to examine, ‘cuz I’ve got to move on to Sunday night’s spectacular double bill.

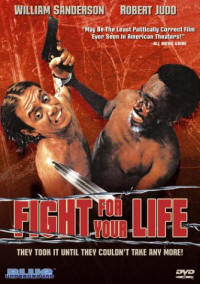

There are two kinds of people in this world: those who have seen Fight for Your Life and those who know fuck-all about cinema. Up until a lovely spring day in April 2004, I shamefully resided in the latter category – not by choice, but by lack of access. For years, Robert A. Endelson’s Fight for Your Life was a great white whale for cult movie aficionados. Michael Weldon of The Psychotronic Encyclopedia only whetted appetites when he wrote, "Most viewers find this movie beneath contempt", if only because the viewers in question were dumpster diving veterans of the 42nd Street circuit. It took something special to get a rise out of these fuckers.

When Blue Underground answered the nervous prayers of grindhouse gluttons the world over – "nervous" because we still weren’t certain what we were getting – by releasing Fight for Your Life to DVD… it was strange, because everyone kind of kept their reactions to themselves. Though I immediately fired off an enthusiastic review for Ain’t It Cool News, there wasn’t exactly a resultant outpouring of praise or opprobrium – this for a movie that lived up to its dubious hype and then some. And this was confounding until I realized that Fight for Your Life wasn’t meant for solitary home viewing; it was meant for a crowd.

When Blue Underground answered the nervous prayers of grindhouse gluttons the world over – "nervous" because we still weren’t certain what we were getting – by releasing Fight for Your Life to DVD… it was strange, because everyone kind of kept their reactions to themselves. Though I immediately fired off an enthusiastic review for Ain’t It Cool News, there wasn’t exactly a resultant outpouring of praise or opprobrium – this for a movie that lived up to its dubious hype and then some. And this was confounding until I realized that Fight for Your Life wasn’t meant for solitary home viewing; it was meant for a crowd.

Late Sunday afternoon, I at last experienced Fight for Your Life with a… maybe three-quarters full house, and though the turnout was a bit disappointing (it should’ve been programmed for Saturday night), the reaction was not. Endelson’s race-baiting variation on The Desperate Hours, written by exploitation veteran Straw Weisman, is too cruelly calibrated; it plays like an unknown, outlaw Terry Southern rewrite of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. William Sanderson stars as the ringleader of an escaped trio of prisoners trying for Canada. Before they cross the border, however, they decide to hole up in the upstate New York home of a black minister (Robert Judd), whose living room is decked out with framed pictures of John and Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. Just to give you an idea of the in-house dynamic, his adolescent son (a young Reggie Rock Bythewood) sports an iron-on Muhammad Ali t-shirt, while grandma (Lela Small) espouses black power platitudes.

The bulk of Fight for Your Life has Sanderson insulting the family with every awful epithet imaginable while the pacifist father insists on turning the other cheek (to drill this exceptionally obvious metaphor home, Sanderson at one point bashes the minister about the face with a Bible). This scenario is excruciatingly indulged so that when the family turns the tables on their captors, the audience should be leaping out of their seat. Passions didn’t explode to that extent during my 5:50 PM Sunday showing, but folks were definitely shouting back at the screen, which was pretty cool. They also howled during the film’s two most brain-rattling slayings (no chance of me spoiling ’em here), and seemed to enjoy the soft-focus interracial love scene between two eminently bored performers.

If you’ve access to a local theater, I can’t stress this enough: you’ve got to book Fight for Your Life as a midnight movie, and round up as many unsuspecting filmgoers as possible. Failing that, at least pick up a copy of the Blue Underground disc and watch it in the company of friends; it ain’t a great movie and it ain’t exactly right, but it is quite something.

The same can be said of Cirio H. Santiago’s The Muthers, a strange hybrid of pirate flicks and women’s prison programmers starring Jeannie Bell (Playmate of the Month October 1969), Rosanne Katon (Playmate of the Month September 1978), Trina Parks (Thumper from Diamonds Are Forever) and Jayne Kennedy (ex-wife of the hopefully immortal Leon Isaac Kennedy and only one of the hottest women to ever walk the planet). The plot has Bell and Katon, leaders of a Filipino band of marauders, infiltrating a female slave colony in order to find Bell’s missing sister. Parks plays the prison scrounger who’s struck up a cooperative relationship with the gay (and, rare for this sub-genre, male) warden’s mistress, lusciously embodied by Kennedy (hey, I watched Body and Soul a lot when I was a kid).

The same can be said of Cirio H. Santiago’s The Muthers, a strange hybrid of pirate flicks and women’s prison programmers starring Jeannie Bell (Playmate of the Month October 1969), Rosanne Katon (Playmate of the Month September 1978), Trina Parks (Thumper from Diamonds Are Forever) and Jayne Kennedy (ex-wife of the hopefully immortal Leon Isaac Kennedy and only one of the hottest women to ever walk the planet). The plot has Bell and Katon, leaders of a Filipino band of marauders, infiltrating a female slave colony in order to find Bell’s missing sister. Parks plays the prison scrounger who’s struck up a cooperative relationship with the gay (and, rare for this sub-genre, male) warden’s mistress, lusciously embodied by Kennedy (hey, I watched Body and Soul a lot when I was a kid).

Santiago, a legendary sleaze cinema figure who directed the needs-badly-back-in-print Stryker, gets Parks topless, meaning he’s due a Lifetime Achievement Oscar any year now. He also fits Bell in a tight brown turtleneck sweater that shamelessly accentuates her two abundant attributes – a fantastic wardrobe choice brilliantly ill-suited to fleeing prison guards somewhere deep in the Philippines. The Muthers also kicks to a tremendously funky main theme that I’ve been chasing down for the last couple of days to no avail. I’d be worried about never hearing it again if I weren’t convinced Tarantino has plans to appropriate it somewhere down the line.

And this, my friends, is the glory of a weekend spent at the grindhouse. For those of you living in the L.A. area, you’ve got another two weeks to partake; for everyone else… find your own prints and do what needs to be done.