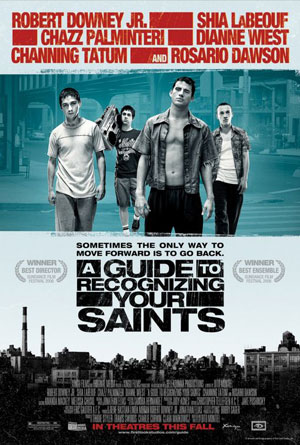

A Guide to Recognizing Your Saints was one of the biggest film surprises I got last year. Based loosely on writer/director Dito Montiel’s own experiences growing up in ethnically mixed Astoria, Queens in the 1980s, the movie is a perfectly evocative glimpse at a New York City now lost to history. But like all the best stories, its specificity makes it weirdly universal, and the lives and tribulations of Dito (Shia LaBeouf), Laurie (Melonie Diaz) and hot-headed Antonio (Channing Tatum in a performance that should get him out of sappy romances soon, God willing) will be familiar to everyone.

A Guide to Recognizing Your Saints was one of the biggest film surprises I got last year. Based loosely on writer/director Dito Montiel’s own experiences growing up in ethnically mixed Astoria, Queens in the 1980s, the movie is a perfectly evocative glimpse at a New York City now lost to history. But like all the best stories, its specificity makes it weirdly universal, and the lives and tribulations of Dito (Shia LaBeouf), Laurie (Melonie Diaz) and hot-headed Antonio (Channing Tatum in a performance that should get him out of sappy romances soon, God willing) will be familiar to everyone.

The movie is now out on DVD, where Dito gives a revealing commentary. You can buy it from CHUD by clicking here, and I can’t recommend it enough – it’s going to go down in the history of the ‘boys growing up’ genre alongside Stand By Me and Breaking Away I had a chance to talk to Dito recently, and he had some really fascinating things to say about the factual truth of movies versus the emotional truth of movies.

I grew up in New York City, and I’m just a little bit younger than you are. It was pretty amazing to see how much your film reminded me of that time period, but things have changed so much in New York since then. How did you recreate that time in this post-Guiliani New York?

It’s definitely tricky, but luckily Astoria, where we filmed, hasn’t changed that much. It isn’t like trying to film in Williamsburg or the Lower East Side, where you’d be in a lot of trouble, I imagine. Luckily here it hasn’t changed all that much.

What was strange is that Eric Gautier was our cinematographer, and he had been to New York just once and for one day, and I was standing outside and I’d say, ‘This building used to be green!’ and he’d say, ‘Yeah, but it looks good yellow.’ We took the ATM signs out of windows and we had enough money for just a couple of older cars. But luckily, if you remember back in the 80s the streets weren’t as crowded, so that helped us. Clothing helps, and I just told everybody, try to make it look like the 70s. I knew that growing up everybody listened to music from the 60s – I’m in Astoria right now and I just heard somebody listening to fucking Bon Jovi – so there is a strange time lapse with everything.

The belief was that if the emotions are right we’ll get away with the technicalities. I’m sure the movie is full of technical flaws; I can only imagine.

Obviously the movie is based on your life… sort of. How important is it to be true to what factually happened in your life versus being true to what’s emotionally correct?

To me that’s two very different questions. The facts get in the way of things all the time, and details do too. If I was trying to make sure commas and periods appeared correctly in my books, they’d never get finished. As far as emotions, for me, that’s everything.

Movies are the weirdest form of art in the whole world, because people think there are rules. When you’re painting no one tells you, ‘You can’t do that!’ You have people telling you that all the time in the movies, and they have good reasons, not dumb ones. But if you listen to that, you’ll never make a movie. Never. You’d never make a painting if people sat there talking about Picasso. You’d shit yourself! So the plan was that if something feels right – and that goes down from the script to the editing to the acting – at the end of the day it comes down to the story of a boy goes away and becomes a man. It doesn’t get any easier than that. It doesn’t get any more normal than that; I’ve seen it a billion times. What we were trying to do was to show what it might feel like to be in those situations.

I’ll give you an example, because I could beat around the bush forever. I had a friend Billy who used to ride on the top of trains, a lot of dumb kids used to do that. Including me. And he fell off and died. Anyway, I wrote this one part based on a kid named Giuseppe, and the real story is that Giuseppe got deported for being a career criminal. Every time I tried to change his name to Billy, because I wanted him to die falling off a train, he didn’t talk like Giuseppe any more. And the kid Billy I knew wasn’t the character I wanted to write about, but I liked the way he died. That’s sick, but I liked it for the movie. So I wrote this thing where Giuseppe, the one who got deported, he used to climb up the sides of buildings like no one I had ever seen, not even a cat could do it. We couldn’t put a kid on top of a train dying, because this isn’t a Harrison Ford movie, so I had Giuseppe get down on the train tracks when he’s having a fight with his brother. When the train is coming he’s going to get up, like a cat, he knows he just needs one second and he’s going to beat it, but I wrote it that he slips and falls. But we started shooting it – we had no rehearsals – and the actor, Adam Scarimbolo, started doing it like a suicide. I stopped filming and I said, ‘No, no, Adam, this ain’t a suicide, man.’ The actor is very similar to this character that he played; he’s a strange guy, I love Adam. He takes me aside, and he says, ‘Well, um, I feel like, uh, the whole script, my brother he won’t tell me he loves me. So if he won’t say it here I’m just not going to come up.’ And I thought, oh my God, this is so much more interesting than what I wrote, so we went with it.

It’s a combination of everyone’s truths when you’re making a movie. There’s a fact, and you put it on paper, and then there’s emotion behind that fact. I had a guy who came up to me, I swear, about three weeks ago in Astoria, and he said, ‘Hey, you should make a movie about me. I used to cut people’s hands off.’ I said, ‘That’s nice to hear. That’s horrifying.’ I left and I thought, I don’t ever want to see this human being again. But then I realized the interesting movie would be WHY does he cut people’s hands off? Not that I’d want to make it. So with Giuseppe, why doesn’t he want to get off those train tracks? I put him there, and I wrote a whole movie about how this kid was neglected and abused and there must be something horrible going on, and the actor took all those facts I put into the script and internalized them in his own way.

The book covers more time, right? It follows you later into your life?

There’s nothing really autobiographical about the book except that I’m always around. I’m there as a reporter, telling the stories of people who were interesting to me. But yeah, it covers a whole bunch of people’s stories.

Why did you decide to focus on just the Astoria stuff in the movie?

Like I said, the book wasn’t autobiographical, and I could care less about biographies – hell, even The Aviator it was tough to get me into the theater, and that was Scorsese. But with this, every time I wanted to write something I just kept going back to Antonio killing someone with a baseball bat. And it’s the little things you remember – I remember my father saying, ‘He’s just a kid, he’s just a kid.’ Somehow I just felt that was the story to make a movie about.

What was it that you made you think you could make a movie? You talked before about people telling you that you can’t make a movie, and it seems so daunting – what was it that made you do it?

I just decided. I was working at a dub room in Los Angeles with my friend Jake Pushinsky, who ended up editing the film and he had never edited anything before – in fact, he had never used an Avid! We got together, and the book had just come out, and we were sitting there and a video camera was there, and we decided to just mess around with it and see if we could do something with it. We filmed this weird little dirty spot on a window on a Los Angeles bus. We took it back and on the Apple computer that was in the dub room with us, we got on it and started messing around. There were a million CDs in the dub room, so we started putting music on it. Antonio called me all the time from prison while I was working out there, so I recorded us talking, and I put him talking over this thing. And it felt good, and I said, ‘Jake, I think we can do this. I think we can do this for an hour and a half.’ The plan was to shoot it on this video camera with me and my friends, whoever would show up to act. Real zero budget, not Hollywood zero budget.

But then Robert Downey Jr came in and this big avalanche of things happened that made it more real. The strange thing about Robert Downey coming into the picture for me, was that we were going to make this film for our friends and there would be no pressure. Then Robert Downey came in, we were jumping for joy, and we thought, ‘My God, they’re not going to let us make this on a video camera now. We have to buy film.’ A weird reality comes in, which can be a bummer when you’re trying to create art.

You had such a great cast – not just the adults, the kids are fantastic. What’s it like working with the younger actors? And how about Channing Tatum – he’s so amazing in this film.

I kept coming to New York and doing open calls because I love movies like City of God or Raising Victor Vargas, where you don’t know anyone. I went to Coney Island and Manhattan, anywhere I could. I put fliers up, I put an ad on Craigslist and it was like American Idol – three thousand kids showed up in the pouring rain. You get mothers showing up with 13 year old girls saying, ‘She looks 18,’ and they don’t even know who I am! We’re at some weird music rehearsal place in Queens and she’s offering this 13 year old girl – are you nuts? But it’s full of that, it’s crazy. One girl I found on a train, Julia Garro, who plays Diane. I saw her and I walked over and said, ‘Listen, I know I sound like a real creep, but I think you would be good. I’m going to give you a number and have your mom call me.’ Luckily she did.

With Channing it was really strange, and it epitomizes what you asked before, about the truth and all that. When Channing showed up, I thought, no way, man. He was from Alabama, blond hair, blue eyes – a male model! The character I wrote was a short, wiry, impossible to love kid from Naples. They couldn’t physically be more opposite. But we hung around, and something about the role appealed to him and struck a nerve in his personal world. He brought this Of Mice and Men thing to it, which wasn’t my intention, this Lenny ‘I broke your neck but I didn’t mean to and I’ll fix you now’ thing. When I saw that it was strange – it reminded me of the kid I wrote about. He would break your neck, but didn’t want to. Same truth, but a different angle.