The Polish Brothers seem like they work slowly – it’s been

The Polish Brothers seem like they work slowly – it’s been

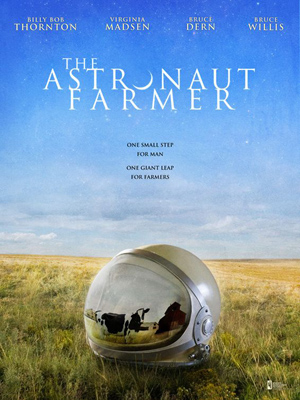

eight years since Twin Falls Idaho, with The Astronaut Farmer only the third

feature to follow their debut. But with acting and writing gigs for other

filmmakers, plus their own research, their output isn’t as surprising.

Neither is their focus on Americana, which has been perhaps

the duo’s most consistent and defining quality. Whether with a Lynchian bent

or, as in their latest film, coming from a more family-oriented perspective,

Mark and Michael Polish are telling stories about this country in a way that

sets them apart from other contemporary American filmmakers.

This

doesn’t seem like a story that quite fits in with what we know from you both –

where did The Astronaut Farmer come

from?

Michael: Every idea that you come up with you want to be

inspired, and hope it gets you to 110 pages. So this was just ‘how about a guy

who builds a rocket in his barn?’ It was really that simple.

Mark: And it comes out of the rebellious nature of

filmmaking. Take the idea that we, as kids, were looking at launches and

realizing that we were never going to get into space. The elimination process

drives out the common person. So it comes from the idea that a rebellious

person could say, well, I’m going to do this anyway. And that relates to us,

and we took the kind of energy that we used in our first filmmaking and applied

it to this story.

Charles

Farmer is almost classic in the way he’s elevated by determination.

Michael: Yeah, definitely. Billy keeps saying this is his Mr.

Smith Goes To Washington. We never set out to make that type of tone,

but I’m happy it worked out that way. We just wanted to make a sort of

archetypical type of film.

Mark: You start with this blank page, and as you render it,

you do so in part because of moves that have to be made financially. So we end

up with this classic house and barn, and those things start dictating the tone.

Because of the limitations of the budget, you make compromises, but they all

play into the feeling.

How

significant were the compromises you had to make? For example, there’s a launch

sequence that must have cost as much as the rest of the movie.

Michael: And in that, there were things we shot that we

weren’t able to finish. He went through someone’s house originally, while the

person was watching TV. We shot that but never finished it. We wanted to make

it like a cartoon.

Mark: We like the Warner Brothers cartoons, and that was the

Wile E. Coyote scene.

Elements

like that help make this potentially a crossover from the art house to

mainstream for you.

Mark: We made this exactly as we wanted to, without the

intention of ‘crossing over’. We approached this like any other, and decided to

find financing as usual, whether it was independent or equity or studio, we had

no idea. We just wanted it to be accepted as it was. So we started off and

Warner Independent was kind enough to give it a chance, and then from that

success Warner Brothers took it over. That process ended up here; the success

has already happened, in our eyes.

Was

Billy Bob instrumental in making that leap?

Michael: Yes. To him, he would have made this movie for

three or four million. We thought about who would be the best guy to become

this person who’s an astronaut and a farmer – two themes going there – and Mark

said that he has the characteristics of both. WE talked to him on a weekend and

by Monday we were ready to go.

Mark: And we had his name before it went out to financiers,

and he just solidified himself in that role. People read it and thought no one

else could play it. It was one more piece that they didn’t have to think about.

And Virginia completed it.

Both

of them are very right for the film; does that make your jobs easier?

Michael: Absolutely. And if they like each other, even

better.

As

an American archetype, there are few more classic images than the astronaut,

but do kids still want to be astronauts?

Michael: In pockets of the US, yeah, they probably do. But

overall I don’t think it’s the same as it used to be. And we’ve had some kids

come to the screenings who want to be astronauts.

Mark: It’s just so iconic. The whole era, the suits, even

the shuttle, is indelible.

Did

your division of labor on this film change at all, or was it business as usual

for you?

Michael: We’re never working in close proximity. We’re

always doing two different things, and it’s like two people running a war. We

don’t even write the script together. One of us will do the first draft, the

other the second, and so on. It becomes a question of who feels more able to

give the most to the story at the time. So here I took the first draft, Mark

took the rewrites and I went into preproduction. Then I’m directing, he’s

producing and is usually in it..there are so many facets that we’re rarely

standing shoulder to shoulder.

Mark: Except in the first film. But really, we know each

others’ strengths, and so only have to conference if it seems like there’s some

question. And I did a really huge amount of second unit, directing well away

from the picture on this time. All the FBI guys were directed by me.

Michael: And it was weird, not that I don’t trust Mark, but

it became that whatever scenes he was in, he had to go do. Because when it came

to crunch, it was like this was still an independent movie. We had less than on

Northfork. And if he was in the FBI scene, it meant he was going to a location

three hours away to shoot. He’s going to come back with the scenes, and that

was weird.

If

you stay on this level, is that how it’s going to be from now on?

Mark: It’s a great idea to get that type of footage, but if

I’m in it…then I’m out there, Dances with Wolves style. And it was

tough for me because I’d never done it. Even on the first film, we were

together. But being in a scene and directing, especially without a full second

unit worth of equipment – we didn’t have a script supervisor or monitors – was

difficult.

Michael: All the scenes he’s in are really guerrilla. Just

basic!

Mark: So I’m out there arresting the pickup truck driver,

and I was terrified.

Michael: We had a great cinematographer, and we were able to

determine how everything would look before hand, and work based on that.

Coming

from small films, is it almost more difficult to make a mid-budget film?

Michael: You’re either really poor, or…but really, it’s all

relative. On Poseidon, you’d hear everyone talking about how there wasn’t

enough money. Every project seems to hang itself no matter what.

Mark: Like they say, whether you have 10 million or 100, the

sun still goes down at the same time every day. You have to deal with that

regardless. And with us, that’s why a lot of the film was shot the way it is.

We’d just grab at the end of the day. You end up taking real advantage of those

natural events. There’s a sunset? What scene can we shoot?

Did

that change how you envisioned the film?

Michael: It actually promoted it. We wanted that classic

Norman Rockwell setting, with a lot of warmth. That illustration feel. We were

able to get more of those tableaus. We were all over New Mexico, and it really

worked. White Sands, Albuquerque, Santa Fe, up where Georgia O’Keefe lived, all

over. People say ‘your cinematography is so beautiful’ and I have to ask ‘do

you see what we’re shooting?’ Just read the light meter and point the camera

and that’s it.

Mark: We’ve had people on forums comment that I broke some

of the rules, like my horizon line isn’t where it’s supposed to be. I was out

there without a cinematographer, I didn’t know there were rules! I just wanted

it to look good. And that sort of binds you in a weird way. I just shot the

stuff the way I thought it looked the best.

Is

that technical hands-on what separates this movie from your others?

Michael: We’re going into a more mainstream type of movie —

not to us, since we wrote this before Northfork, but to other people. And

people have said, is it OK that you made a feel good movie? And why does it

have to be OK? Why is it bad to feel good. We all grew up watching action

movies, sad movies, comedies, and for all of them it seems like you never went

into them and tore them apart the way people do now. The cynicism…it’s not that

you want to be graded on a curve based on your subject matter, but you want

people to enjoy the experience.

Would

you ever write something that doesn’t have the Americana sort of feel?

Micahel: We’ve written other stuff on assignment, so yes.

And we write what we want to make. We were writing a science fiction movie when

this idea came up. We were getting stalled with some aspects of that story, and

Warner Brothers wasn’t going along with some aspects of it, so we threw this

one out.

Mark: That one is definitely not Americana. It’s a more

hardcore science fiction piece about identity and the commodity of life.

Michael: in a way it’s related to America, the current state

of America, at least. It’s hard to get away from how juicy this country is.

There’s so much to draw on.

Mark: We invented the Mob! That’s great!

Michael: It’s so rich! You’ve got jazz and rock and roll

stories, science, this country has had so much interest. I mean, it would be

fun to run around Europe with a Super 8 camera and make a love story, but

that’s not really us.

Or

you could just watch Breathless.

Mark: You’re kind of responsible for the land you live in,

in a sense. You have to tell those stories.

A

lot of people don’t see that, though. They see their place as limiting, and

they want to go over there.

Michael: People always have an exit plan. But that’s what

makes this country beautiful: it’s so diverse. People don’t have to be locked into

one mentality. It’s nice that we can go from Twin Falls Idaho to this.

Americana,

to a lot of people, just means kitsch, though.

Mark: It’s become derogatory. If you say ‘that’s such a

great American film’ it sounds like an insult.

Michael: Well now, when I think of America, the term, I

think of it like a Ralph Lauren catalog. It’s a look. You think of it as a

fashion thing. It’s been commoditized and sold. And if you want to use it as a

label, that’s fine. But Americana to me is something that has a lot more going

on.

Mark: Because of the issues we’re having globally, I suppose

that’s why it feels derogatory to me. The word has become so promoted and

shoved down people’s throats it’s hard to escape that. But the basic people’s

ideals that we have, that’s something that’s great. Even if it’s impossible to

live up to them.

Does

your feeling there make this a political film?

Michael: It totally does.

Mark: It’s politicized, yes. When we were in Washington DC

there were people making jabs…

Michael: Well, be specific. It wasn’t people. It was the

Washington Post, and nobody but them. They were reacting to the political jabs

we have in the film, and they weren’t going to cover it. But it’s easy to see

why people might not be excited any more about what the space program is about,

and we’re reflecting that.

It

would be hard to be excited in the same way now.

Mark: Now, with the space shuttle, you’ll hear about a

launch and a re-entry, or about a repair. That’s it. That’s what it’s come down

to. It’s like you’re seeing the plot points between explosions in a disaster

film.

Michael: Though it’s still inspiring, the idea of going to

space. There are no limitations. And that’s what still sparks something for

people. And that’s why something like Close Encounters floored us.

Mark: Although — do you know what NAMBLA is? — I heard

that’s a favorite movie of theirs, that their favorite image is this grown man

walking among naked, alien little boys.

Do

you monitor the internet at all, in terms of reaction to your films?

Michael: I really stay away from it. I can be corrosive.

Mark: The first film, it wasn’t as bad, because the internet

was young, so there was more actual talk.

Michael: I love to read people’s insights. It doesn’t have

to be a review, but I like reading critical thinking. That’s really interesting

to me. But a lot of the criticism, to any film, takes personal shots and just

goes for the bash. You even get big papers doing it. And they write about

production in the review, which seems insane to me. That sort of thing has no

place in a review.