Hollywood loves a good franchise. The movie-going public does too. Horror, action, comedy, sci-fi, western, no genre is safe. And any film, no matter how seemingly stand-alone, conclusive, or inappropriate to sequel, could generate an expansive franchise. They are legion. We are surrounded. But a champion has risen from the rabble to defend us. Me. I have donned my sweats and taken up cinema’s gauntlet. Don’t try this at home. I am a professional.

Let’s be buddies on the Facebookz!

The Franchise: Psycho — following the deadly legacy of the Bates Motel and its primary caretaker, Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins). The series launched with Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 landmark adaptation of author Robert Bloch’s novel of the same name, and spawned over the next 38 years three sequels, a failed TV series that was converted into a failed TV movie, and the most infamous remake in recent cinema history. We shall be checking in over night on all six Psycho installments.

The Installment: Psycho (1960)

The Story:

Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) is in a wee bit of a pickle. She lives in Pheonix, but she’s in love with a divorced man, Sam Loomis (John Gavin), who runs a hardware store in the fictional town of Fairvale, California. They must meet in hotels and motels, their love kept out of public. In a poorly thought out bid to be with her man, Marion steals $40,000 (more than $300,000 in today’s dollars) from one of her boss’s clients and makes a break for Fairvale. After stupidly attracting the attention of a highway patrolman and getting lost in a rainstorm, Marion decides to stop off for the evening at a secluded motel run by a charmingly awkward nerd, Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), who lives alone with his ailing mother. Um, spoiler alert? Marion all sorsta gets killed by Norman’s deranged mother and Norman is forced to cover up the crime when a persistent private detective named Milton Arbogast (Martin Balsam) comes looking for Marion. Ditto for when Marion’s sister Lila (Vera Miles) and Sam come looking too. Then a huge twist punches us in the face! Spoiler alert: Norman Bates was Keyser Soze all along! And Keyser Soze was dead the whole time and didn’t even know it! Plus Darth Vader is Luke Skywalker’s dad, soylent green is made out of people, and Sean Bean dies.

What Works:

To say that there is a lot to say about Psycho is an understatement. One of the most enduring, most pivotal, and most fondly remembered films from a director who would surely place on any sane film historian’s Top 10 Most Important Filmmakers of All-Time list, Psycho is not only credited with modernizing the horror genre, but also with changing the very way audiences watched movies (of any genre) in the movie theater. Its influence runs deep. Eighteen years after Alfred Hitchcock inadvertently became the grandfather of the modern Slasher film, John Carpenter paid homage to Psycho by naming Michael Myers’ pursuer Dr. Samuel Loomis after John Gavin’s character in Psycho, Sam Loomis (very subtle John). Then eighteen years after that, Kevin Williamson paid homage to Carpenter’s homage in Scream by naming Skeet Ulrich’s character Billy Loomis. (By my math we’re due for another reinvention of the Slasher subgenre with another Loomis homage in 2014!) Psycho‘s finger prints are so pervasive that its disciples and rip-offs went on to inspire their own disciples and rip-offs! Point being, in the past fifty years Psycho has become more than just a movie, it’s the kind of classic that has been absorbed so fully by the cinema collective, warts and all, that it now defies any real sense of criticism. But for the purposes of this column, let’s try and treat the film like it came out this weekend; as much as is reasonably doable.

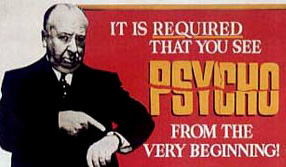

The twists! There is a lot that works about this movie, especially on one’s second (or third or tenth) viewing. There are layers to be found and filmmaking craft to be savored. Hitchock was a true artist of the cinema form, but above all else he was a showman first, an A-list William Castle. And  Psycho was his ultimate “show.” Like a magic trick, Hitchock seems more concerned with goosing our expectations than he does in delivering a “satisfying” narrative. As his then radical advertising campaign – in which potential viewers were told they must see the film from beginning to end (unorthodox at the time) – proves, Hitchcock constructed the film to surprise the ever-loving fuck out of us. It is the kind of movie you will surely always wish you could go back and watch again for the first time. Which makes it a tonally excellent adaptation of Robert Bloch’s novel, which features the same big twist at the end: that Mrs. Bates has been dead for years, murdered and mummified by Norman, and that Norman has a split personality that believes itself to be an uncontrollable Mrs. Bates; revealed by Norman running into a room dressed as Mrs. Bates and swinging a knife. Hitchcock could have made a brilliant film by simply following the structure of Bloch’s novel, but he was not satisfied having only one mind-fucking twist. He was greedy for more. And here is where he made a make-or-break decision that turned Psycho from a brilliant film into an indelible cinema classic: using noob screenwriter Joseph Stefano’s idea of taking the doomed minor character of Marion Crane (named Mary in Bloch’s book) and beginning the film from her perspective. Killing your protagonist at the end of a film is always a ballsy-verging-on-stupid move for a filmmaker. Killing your protagonist midway through the film just seems flat-out incompetent. Only someone like Hitchcock, already decades into a ragingly successful career, and a career known for toying with audiences, would ever try such a sadistically ill-advised rug-pulling on us.

Psycho was his ultimate “show.” Like a magic trick, Hitchock seems more concerned with goosing our expectations than he does in delivering a “satisfying” narrative. As his then radical advertising campaign – in which potential viewers were told they must see the film from beginning to end (unorthodox at the time) – proves, Hitchcock constructed the film to surprise the ever-loving fuck out of us. It is the kind of movie you will surely always wish you could go back and watch again for the first time. Which makes it a tonally excellent adaptation of Robert Bloch’s novel, which features the same big twist at the end: that Mrs. Bates has been dead for years, murdered and mummified by Norman, and that Norman has a split personality that believes itself to be an uncontrollable Mrs. Bates; revealed by Norman running into a room dressed as Mrs. Bates and swinging a knife. Hitchcock could have made a brilliant film by simply following the structure of Bloch’s novel, but he was not satisfied having only one mind-fucking twist. He was greedy for more. And here is where he made a make-or-break decision that turned Psycho from a brilliant film into an indelible cinema classic: using noob screenwriter Joseph Stefano’s idea of taking the doomed minor character of Marion Crane (named Mary in Bloch’s book) and beginning the film from her perspective. Killing your protagonist at the end of a film is always a ballsy-verging-on-stupid move for a filmmaker. Killing your protagonist midway through the film just seems flat-out incompetent. Only someone like Hitchcock, already decades into a ragingly successful career, and a career known for toying with audiences, would ever try such a sadistically ill-advised rug-pulling on us.

What makes the untimely and very unexpected death of Marion Crane extra devilish isn’t just that our heroine dies at the 49-minute mark, suddenly forcing us to shift our focus and reinvest in a new central character, but that our new central character is a villain! While we’re still supposed to believe that Mrs. Bates did the actual killing (making Norman something of a victim here himself), Norman’s sociopathic lack of remorse over Marion’s grizzly passing doesn’t exactly paint him as a swell guy. Yet Hitchcock effortlessly reframes the whole damn movie so that we actually find ourselves almost immediately rooting for this creepster piece of shit, despite our better moral judgement. The way Hitchcock accomplishes this is representative of his power and style, which was always deceptively simple seeming, belying a wizard’s power of manipulation. After Norman discovers his mother’s work, ie Marion naked and dead on the bathroom floor, he sets out to methodically clean up the mess. We see the whole process, him being worried, him deciding to cover up the crime, him mopping blood, moving and wrapping up the body, with only light scoring and the shower water still running for a good chunk of the sequence. If Hitchcock had skipped over this outwardly boring series of events, and had simply jumped to Norman sinking Marion’s car into the swamp, he would not have been able to as effectively goose us with one of the film’s best gags — As Marion’s car sinks into the water, it suddenly stops, left conspicuously protruding above the surface. Hitchock makes your heart stop for a second. Oh no! you can’t help but feel! Then the car resumes its descent beneath the surface, and you relax as Norman relaxes. And then you have to laugh, realizing Hitch has just pulled a macabre prank on us. We’re empathizing with this fucked up weirdo! The same creep we saw spying on Marion getting dressed mere minutes ago! And it is all because we had to watch Norman painstakingly clean up the mess. It is elementary movie math. After all that, with Norman so close to getting away with it, you can’t help but get tripped up when it suddenly seems like he won’t. Dark humor at its best. And now we’re hooked in. When Arbogast is hounding Norman later on, you don’t get tense waiting for Arbogast to nail him, you get tense watching Norman’s increasingly bad lying because you don’t want Arbogast to nail him.

Though Anthony Perkins is technically awful casting for a character who was fat, alcoholic, and middle-aged in Bloch’s novel, it is hard to imagine – even with Hitch’s powers of manipulation – that we could have gotten sucked in by Bloch’s Norman after our previous protagonist’s death. The Marion twist would have needed to be abandoned. But casting someone so completely against type like Perkins was a bold and clever move (one that ended up re-type-casting Perkins and effectively ruining his career). If Psycho came out today we’d call Perkins’ Norman Bates “adorkable” in his early scenes. You like him. He’s a bit weird, getting a bit too mad when Marion bad mouths his mother, but you feel for him because of how Perkins plays the character. His creepiness is initially mistaken for sheltered social innocence. I love that Perkins’ performance is consistent throughout. There is no need for a stupid What Lies Beneath-style 180 attitude change once it is revealed that dubious things are afoot. From beginning to end Perkins remains the same. It is our attitudes that change.

Janet Leigh is used pretty shamelessly as exploitation, repeatedly de-shirted and ogled by the camera, but since this was Hitch’s goal, I suppose praising how well Leigh’s look lends itself to such a role is appropriate. She looks practically sculpted. She is a stellar prop. Beyond this, it is hard to get a true sense of personality (Leigh was the weakest actress of Hitchcock’s blonde muse era), but given that the whole character is a fake-out it hardly matters — Marion dies just as we’re getting to understand her. This isn’t to say that Leigh is bad, but her dialogue only clicks when it is supposed to be sultry; “I’ll lick the stamps.” But I’d still count her as a positive element. The best bit of casting after Perkins is the always fantastic Martin Balsam, who, unlike Leigh, infuses the delightfully named Arbogast with fountains of personality. Frank Albertson is excellent in the small but memorable role of Tom Cassidy, the wealthy loudmouth who Marion steals the $40,000 from — some of the film’s best quotes come from Albertson’s first scene. Hitchcock’s daughter Patricia also turns in a hilarious bit part as Marion’s married and clueless coworker Caroline. I love the line, after Cassidy has been flirting with attractive Marion, when Caroline says: “He was flirting with you. I guess he must have noticed my wedding ring.”

Bernard Herrmann’s score. Few films have benefited more from their scores than Psycho. Herrmann’s music frays your nerves; at times it feels like it is attacking you, stabbing you with those shrieking violin scrapes. Beginning the film with the Psycho theme over Saul Bass’s jaunty and fractured opening credits animations slides us into the movie with the right attitude for what will eventually come, even though we have to wait nearly an hour for it.

As with most Hitchcock classics, we could easily go through almost the entire film talking about how great every scene is, but all the juicy stuff – namely a certain shower scene – has been so thoroughly chewed over since 1960 there just isn’t much flavor left. So forgive me for leaving things at: Psycho has a half-dozen truly amazing scenes, both big and small.

Speaking of small, Psycho is a very small movie once we reach the Bates Motel. But Hitchcock makes the most of the locale. The Bates house (it kinda bugs me when the house gets referred to as the ‘Bates Motel’) is placed on a modest hill, but Hitch always shoots it from extreme lower angles against a horizon-less big sky that turns it into a haunted castle perched atop some craggy peak. This makes the house’s mysterious inhabitant, Mrs. Bates, seem distant and powerful, a Grendel-esque beast that descends from the hills to terrorize the villagers below. There is also something of a metaphor here, with the multi-teired location representing Norman’s fractured mind. The house on the hill can be seen as Norman’s nagging conscience, his strict superego. The motel below represents the base temptations of the world, Norman’s id. Norman tries to be normal, talking with girls, engaging his sexual urges to spy on girls; he even has a little home here in the normal world in the motel’s office. This, in a way, is where Norman lives. The house is where Mrs. Bates lives, watching Norman from her window throne and judging him. When he’s misbehaved, giving into these base temptations, he must ascend into the house to become his superego form. And because he always dresses as Mrs. Bates when carrying out her will, there is a very literal aspect to this process. He can’t become Mrs. Bates unless he ascends the steps up to the house. I don’t think this is subtext that Hitchcock necessarily needed us to decipher, so much as it is just a window into how Hitch constructed his work. The Bates house would not have been as effective and certainly not as iconic if it hadn’t been on a hill and if Hitchcock hadn’t always framed it from below. It is hard to imagine the movie with the house being on the same level as the motel. This basic decision turns Psycho into a monster movie. When Arbogast or Lila venture up into the home it evokes a similar feeling to Harker or Van Helsing venturing into Dracula’s castle, where we know the creature slumbers somewhere within — a feeling evoked even further by Norman moving Mrs. Bates down into the cellar.

What Doesn’t Work:

Proportional to how brilliant the rest of the film is, Psycho may very well have the worst ending in cinema history. Roger Corman astutely once said that your movie was over when the monster is dead. In other words, don’t dick the audience around after the climax. Hitchcock was of the same mind on most of his films – most notably the charmingly sudden epilogue of North by Northwest – but having just pulled a doozy of a twist on the audience, Hitch seems insecure about our ability to grasp what it all means. After Lila finds Mrs. Bates skeletal corpse and Norman runs in wearing the dress we get a nearly ten-minute-long epilogue featuring an embarrassingly expositional monologue from a character we’ve just met, forensic psychiatrist Dr. Fred Richmond (Simon Oakland). This lengthy section displays zero nuance and the tone of the dialogue suddenly gets corny. Even if we grant that maybe 1960 audiences didn’t know all the clinical mumbo-jumbo behind what a psychopath is, they can’t possibly have needed Richmond’s only marginally accurate description to make them understand that Norman is crazy, mummified his mother long ago, and has been pretending to be her. The pieces were already there for us to be following along. In any case, there had to have been a less clunky and energy-zapping way to have given us this info. For a movie that already has a disjointed narrative, handing the reins to a brand new character (Dr. Richmond) makes the film come off as nearly episodic. The only thing that saves the epilogue is an excellent closing scene featuring Mrs. Bates scheming silently inside Norman’s head in a voice over.

Both John Gavin as Sam Loomis and Vera Miles as Marion’s sister Lila are dull casting choices. This may be an unfair criticism to make for an older film, but they seem like they were created by a machine programed to produce generic actors and actresses specifically for 1960, which is made all the more evident by placing them next to unique types that stand the test of time like Balsam, Perkins and the great character actor John McIntire as Sheriff Al Chambers.

The twist that Norman and Mrs. Bates have been the same person all along is the kind of thing that is very easy to pull off in a novel, and extremely hard to pull of in a film. Hitchcock pulls it off, because he is Hitchcock, but he cheats a little. He probably had to cheat a little, but nonetheless it is suspect once the twist is revealed and we’re suddenly left to determine that Norman is the Frank Welker of serial killers, able to perfectly mimic the voice of an old woman and carry on conversations effortlessly skipping between two distinct characters. The cheat is that Hitchcock uses the voice of an actual older woman (several, I believe) when we hear Mrs. Bates talking. If this was all in Norman’s head that would make sense, but other characters overhear Norman talking to himself. He is speaking aloud. Hearing what is clearly a woman speaking helps dispel the doubts that would naturally arise for us as we realize we never get to see Mrs. Bates’ face, but it is a cheat all the same. Hitchcock was steering for the big final shocker, not air-tight plausibility.

Body Count: 2

Best Kill: Marion’s shower scene. Though Hitchcock’s strange staging of Arbogast’s death is bitchin’ too, with the insane shot of him improbably stumbling backwards down the stairs after “Mrs. Bates” slashes his face with a knife.

Best Norman Line That Really Should Have Tipped Someone Off: Said to Marion. “We all go a little mad sometimes.”

Best Mrs. Bates Line: I won’t have you bringing some young girl in for supper! By candlelight, I suppose, in the cheap, erotic fashion of young men with cheap, erotic minds!

Stupidest Line: After Lila asks him if Norman killed her sister.

Dr. Richmond: Yes… and no.

Does the Twist Ending Hold Water: Yes. The seclusion of the motel makes it entirely plausible that Norman could have had his mother’s corpse without anyone knowing. And based on what Richmond deduces at the end, Norman has only killed two other patrons in the past, both of whom were missing persons who were never connected to the Bates Motel.

Should There Be a Sequel: Well, our antihero is still alive, and the film does end with Mrs. Bates sinisterly plotting inside Norman’s head. So the door is open. But given that 50% of the power of this film came from the Marion fake-out and twist climax, trying to create a sequel that captures the same surprising feeling as this film seems like a fool’s errand.

Up Next: Psycho II

DISCUSS THE FRANCHISE ON THE BOARDS

previous franchises battled

Critters

Death Wish

Hellraiser

Home Alone

Leprechaun

The Muppets

Phantasm

Planet of the Apes

Police Academy

Rambo

Tremors