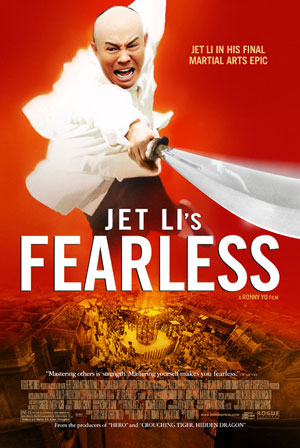

Ronny Yu’s career has spanned both sides of the Pacific Ocean, and has included Chinese films like The Bride With White Hair and Hollywood ones like Freddy vs Jason. His latest is Jet Li’s Fearless, the philosophical martial arts movie Li has been wanting to make for years. Set in the time just before WWI, Fearless is about a wushu master who becomes full of himself and loses the point of martial arts – for him it’s all about winning and maintaining face. When he makes a terrible mistake that turns into a bloody tragedy, he wanders off into the wilderness to reconnect with the spirit of wushu.

Ronny Yu’s career has spanned both sides of the Pacific Ocean, and has included Chinese films like The Bride With White Hair and Hollywood ones like Freddy vs Jason. His latest is Jet Li’s Fearless, the philosophical martial arts movie Li has been wanting to make for years. Set in the time just before WWI, Fearless is about a wushu master who becomes full of himself and loses the point of martial arts – for him it’s all about winning and maintaining face. When he makes a terrible mistake that turns into a bloody tragedy, he wanders off into the wilderness to reconnect with the spirit of wushu.

The film is often gorgeous, and the message is right on without sacrificing the kind of ass-kicking action you would expect from a Jet Li movie. Last week I got on the phone with Ronny, who told me his very interesting insights into what’s wrong with Hong Kong filmmaking. He also told me about his adaptation of Blood: The Last Vampire, which is different from what he told Aint It Cool News in an interview some time ago.

Q: When Jet Li approaches you to direct his last martial arts film, is there something you guys decide has to be in the movie because it’ll be the last chance?

Yu: I guess the entire movie. I’m serious. I think that’s one of the reasons he said this was his last picture – we don’t want to use ‘martial arts,’ we want to use ‘wuxia’ because martial arts is too generalized. Karate is a martial art. Korean fighting is also a martial art. But wushu is really the traditional Chinese martial art. We want to use this opportunity to let the Western audience understand there’s another genre called wuxia, Chinese wuxia, because very easily people confuse… people think Crouching Tiger or my previous film, The Bride With White Hair or Hero or Flying Daggers, they think, ‘Oh, those are martial arts movies!’ Those are not martial arts movies – those are called wuxia movies, and those are not real. They’re like Lord of the Rings, where there’s fantasy and magic and people can fly – people can fight in trees and in the middle of a lake and all.

In order to qualify as a wuxia movie the actor himself has to be a traditional Chinese martial arts wushu – not just the techniques, but he must understand the philosophy behind it. I think right now out of all the actors only Jet Li is qualified to do that. And he’s 43 years old and he doesn’t know how long he can keep up with all the wushu action sequences. He also finds the character that he portrays in the movie shares his own philosophy about Chinese wushu.

He wants to use this movie to tell all – that’s why he says this is his last wuxia movie. It’s not his last action movie; he’ll still hold a gun or do kicks and all that, but I think most importantly what he’s trying to say is the philosophy behind it.

Q: I’ve interviewed Jet Li in the past and he definitely likes to talk about his own philosophy behind the wushu. But the wuxia genre is very over the top, stylized and action-packed – how do you make sure the message is getting across to people who are coming to the theater just to see fights?

Yu: I think most importantly you have to start from the story. You have to start from the story and you have to start from the character. Basically the story and the character itself had to go back to the basics, be grounded, be a real person and not be some fantasy character where you don’t understand their feelings, don’t understand their emotion. You just understand they can do fantastic things. Then it’s part of the problem with all the quote  unquote kung fu movies or chopsockey movies, where people don’t need to understand the characters, they just fast forward to the action sequences without caring about all the drama. In all the previous kung fu movies the filmmakers don’t even pay too much attention to the character development and the story, they just say, ‘Oh, I’ve designed some fantastic moves.’ I think it shouldn’t be that. I think movies should start with story and character.

unquote kung fu movies or chopsockey movies, where people don’t need to understand the characters, they just fast forward to the action sequences without caring about all the drama. In all the previous kung fu movies the filmmakers don’t even pay too much attention to the character development and the story, they just say, ‘Oh, I’ve designed some fantastic moves.’ I think it shouldn’t be that. I think movies should start with story and character.

Q: Do you think American audiences are ready for a serious character-based wuxia film?

Yu: I don’t think there is such a distinguishable thing where this is an American audience, this is an English audience or this is a Chinese audience. I think all cinema language is the same because all movies that we see are about human emotions. Human emotions have no barrier. It doesn’t matter if you’re white, black, yellow or whatever. And it doesn’t matter where you live – it doesn’t matter if you live in Japan or Beijing or Johannesburg or Pittsburgh, it’s all about human emotion. I don’t think that this movie, even though they’re speaking Mandarin dialect, that will make a difference. The story is all about a man’s journey, a very simple man’s journey. About a misguided martial artist and how he makes a mistake, and how he finds enlightenment and how he realizes where his responsibility is and what his duty is in the world and how he can use his talent to save his fellow countrymen. That’s a very basic human story.

Q: You’ve done some horror films in the past, and now you’re doing Blood: The Last Vampire. Do you see that as a horror film or as an action film?

Yu: The reason why I make movies is that I really want to challenge myself. How can I make an old genre to be new? How do I inject some new element into a genre that makes it… I’m not saying cross over, but make an old genre look fresh? Basically Blood is, from the outlook, is a vampire movie, but I am trying to inject something new into it in terms of the look, the tone and the theme. Hopefully the audience can get a little bit more out of it rather than just go in and see gore and blood and violence and all that.

Q: You’re moving Blood from the 60s back to right after WWII. Besides the imagery of the bombed out city, what are you hoping to get from that change.

Yu: That was very, very early on. Now I am back to the 60s. I’m back to the Viet Nam war.

Q: You mentioned before how audiences are audiences and they react to human stories. You’ve worked in China and you’ve worked in Hollywood… recently you ended up not making Snakes on a Plane because you wanted to kill Samuel L Jackson. Do you think that’s an American problem, not wanting to kill the hero?

Yu: On the contrary what I learned from making movies in Hollywood is to really tell stories. The technique of telling stories. I found that is the most exciting thing I learned, how to make a story simple. How to tell a simple story so anybody can understand and identify.

The technique of telling stories. I found that is the most exciting thing I learned, how to make a story simple. How to tell a simple story so anybody can understand and identify.

The reason why I decided to not make Snakes on a Plane… killing Samuel L Jackson was just one of the reasons. There are of course other reasons. But in Hong Kong I think we got stuck into a way of storytelling that almost only the Chinese can understand. That can make the world, when they look at Chinese film, they look at it as a certain kind of movie because they don’t understand it – ‘We don’t need to understand it, but we love the action. We don’t really understand why these characters do thing, but the action is great.’ I think when we’re making movies in Hong Kong we’re more concerned with giving them action. Don’t worry about explaining things, let’s move, let’s move.

Look at Steven Spielberg movies. Look at James Cameron. Look at Michael Mann. Look at Ridley Scott – they can still make a fantastic, fast paced movie but they can still follow the characters. They can still get human emotion in the story. That’s what I learned from Hollywood.

Q: Hollywood has taken a real interest in Asian films and have been remaking a lot of Asian films. Scorsese’s take on Infernal Affairs, The Departed, opens in a couple of weeks. Does that annoy you to some extent? Do you wish they would bring the original here?

Yu: Again, I think it’s the language. I think it’s Hong Kong society, the whole cultural thing. Maybe some people can understand but I think the majority of people won’t understand why they behave in such a way. Every culture has their own way of interpreting things or expressing… if you look at Infernal Affairs, it’s so different the way the Triads behave versus the Mafia. I think a remake helps cut down the barrier and make it more American friendly.

Q: Would you remake a Hong Kong film in Hollywood?

Yu: If I found something exciting and found it could be easily translated without losing the spirit of the movie, I would do it.