Note from Devin: Jeremy Smith is a good friend of mine, and more than that, he’s one of the best writers on the internet. It’s a real coup to have him pitch in and do a one on one interview with Brian De Palma for us. You can read Jeremy’s stuff regularly at Collider.com.

Note from Devin: Jeremy Smith is a good friend of mine, and more than that, he’s one of the best writers on the internet. It’s a real coup to have him pitch in and do a one on one interview with Brian De Palma for us. You can read Jeremy’s stuff regularly at Collider.com.

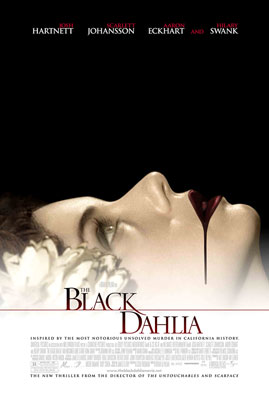

“What’s it like to work with Scarlett Johansson?” I may not be the most adept interviewer, but I’m not about to blow my twenty minutes with Brian De Palma at the historic Biltmore Hotel in downtown Los Angeles with so routine a query. Actually, it’s the director himself posing the question, only it’s with weary sarcasm and to no one in particular – a grim acknowledgment of the boilerplate interrogations he’ll be enduring all day at the hands of personalities from Entertainment Tonight, Access Hollywood, Extra and all the other glitzy, low-cal entertainment news shows.

It’s the prospect of these interviews, and how they might darken the mood of the junket-loathing De Palma, that worried me prior to conducting the below interview with the man I consider America’s greatest living filmmaker. But, while clearly worn out from attending three festivals – Venice, Edinburgh and Deauville – over the last couple of weeks, De Palma is actually quite friendly and very ready to discuss that which he’s endlessly discussed since mid-August. What he doesn’t seem to know before we get into it is that the timid guy armed with two pages of notes seated across from him has been looking forward to this day since the summer of 1987, when The Untouchables offered escape from familial discord and an awkward transition into young adulthood. Never mind that said timid guy has since downgraded The Untouchables to second-tier De Palma; after all, rare is the thirteen-year-old who connects fully with Blow Out and Body Double (though the latter was certainly held in high regard for reasons not entirely owing to superb craftsmanship). There’s a point where you begin to identify the nuances of visual storytelling and the presence of symbolism, metaphor and theme, and that moment for me was my first viewing of The Untouchables. Though I knew I wanted to make movies before that, the idea of being a “filmmaker” didn’t exist until I beheld the union of De Palma and David Mamet.

So you’ll hopefully excuse the personal bias that permeates this interview and keeps it from becoming the bare-knuckle, film-by-film examination of De Palma’s career that I’d love to conduct with the man at some point. Apropos to the two main characters of The Black Dahlia, consider this a tentative, feeling-out Round One of what might be a Fifteen Round bout in the future. Or not. The filmmakers of the 1970s – e.g. Spielberg, Scorsese, Coppola and Malick – have all successfully avoided comprehensive analyses of their oeuvres thus far, and this is probably a good thing since they all seem to be at interesting crossroads. Spielberg is growing more cynical, Scorsese more anonymous and De Palma… well, he just needs a hit to go wherever it is he appeared to be headed with Femme Fatale.

FYI, the ending of the movie is discussed very early, and it’s different from the book. For good measure, the ending of Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye gets spoiled, too. You have been warned.

FYI, the ending of the movie is discussed very early, and it’s different from the book. For good measure, the ending of Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye gets spoiled, too. You have been warned.

This movie completely surprised me. All these years, I’ve been telling people to interpret your films in a formalist framework, and The Black Dahlia is a classical film noir.

De Palma: Thank you!

Was this due to the very rigorous and complex narrative that James Ellroy laid down in the book?

De Palma: I tried to stay very close to the Ellroy book, and, if it got a little too complex, so be it. That’s the way he told the story. I did not try to straighten out any of the kinks or curves. His sort of approach is that there are a lot of questions unanswered, and once you confirm something… like when Scarlett says “He had a little sister,” and then Josh says, “Oh, that explains it,” and she says, “That explains nothing”, you go [indicates exasperation and laughs]. You get an answer to a question, but that just opens up more questions. It’s not CSI. It’s not Law & Order. It’s a mystery within a riddle. I mean, it’s all there, but there are a lot of ends not tied up, as I think Ellroy wanted to suggest. His mother was murdered; they never found a solution. I think that’s pervasive in his work.

While this is a very different film for you in terms of form, Bucky strikes me as a classic De Palma protagonist. A guy who compromises just a little bit, makes one false move, and he’s punished for the rest of the film.

De Palma: Right.

And he will be haunted for the rest of his days.

De Palma: That’s correct.

Is this what attracted you to The Black Dahlia foremost?

De Palma: Well, when you’re dealing with these compromised characters, like all those Humphrey Bogart movies… he’s a little less compromised than anyone else, but he’s still dirty. [Bucky Bleichert, played by Josh Hartnett] takes a tremendous amount of guilt on for something that he’s obviously being set up as a patsy for. Scarlett [Johansson, playing Kay Lake] finally reveals it in the scene after they find the money. He thinks his partner saved his life, but his partner just set him up to witness something that looks like someone getting killed in a crossfire, while it was really an assassination. But he’s carrying the guilt of not saving his partner; and by calling him, Georgie [played by the great William Finley!] slips the wire around his neck. It’s twisted two ways. The more I think about it, he had a relationship with him, but the guy was dirty and used him as a patsy. But he still feels guilty about getting him killed and sleeping with his girl. It’s Ellroy. There’s no way out! (Laughs)

the guy was dirty and used him as a patsy. But he still feels guilty about getting him killed and sleeping with his girl. It’s Ellroy. There’s no way out! (Laughs)

But the guy who’s punished the most is the guy who’s more principled than the rest of them. The people who are comfortable moving in this world, they just go on their way and crawl back under the rocks.

De Palma: That’s right. And look at the way Hillary [Swank, playing Madeleine Linscott] taunts him in the end! “You’re not a fighter; you’re a boxer. You just want to fuck that poor dead girl.” (Laughs) Oh, my god! And, of course, in the book she doesn’t die. But I felt this reptile had to go down. And it’s not like he cleverly covered up the murder. (Laughs)

And it’s great that you just leave that hanging. How’s that going to be dealt with? She’s from a very wealthy family, so it’s probably not going to end well for Bucky.

De Palma: No.

But that moment of wrath, when Bucky kills Madeleine, it reminds me of Altman’s The Long Goodbye. It’s shocking. You don’t expect that from Marlowe, and I don’t expect it from Bucky.

De Palma: Which exactly?

The scene at the very end where Elliot Gould shoots Jim Bouton. It’s just unexpected.

De Palma: Oh, right. I remember saying early on, “He’s got to kill her.” And everybody going (skeptically), “Okay.”

Is it one of those cases where everyone’s saying, “Do you want to alienate the audience again?”

De Palma: She’s got to die! And then I thought, “Should he cover up the crime?” And I said, “Nope. I don’t think he should do that. He should just [shoot her] and walk away from it.” So that’s what we did.

By now you’re certainly aware that your more creative impulses tend to divide audiences.

De Palma: Oh, yeah.

Have you made peace with this?

De Palma: It’s funny. When a critic defends me, they’ve got a lot on their plate. (Big laugh)

Tell me about it. I have never been attacked more savagely than when defending your movies.

De Palma: It’s rough. Who’s the reviewer from the L.A. Times? She’s at the New York Times now.

Manohla Dargis.

Manohla Dargis.

De Palma: She was defending Femme Fatale, and oh boy! (Laughs) But, boy, did she rip up the people that came after me [in her “Ask Manohla” column that her Times editor would do well to reintroduce]. Whoa! More power to her. I need all the help I can get.

I don’t know. I don’t really know. It’s not like something I look to do; it’s just that these are what my instincts are when I make a piece and I feel it’s right. I’m used to the controversy. With Body Double and Scarface… it was vicious.

I watched Body Double the other night, and I’ve always been struck by the end of that movie. It feels like your answer to the feminists’ criticism of Dressed to Kill. I’ve always loved that last scene where Craig Wasson’s trying to help Melanie Griffith out of the hole, and she’s refusing. I always felt that was you saying, “I’m on your side! Seriously, I’m on your side.” And it’s like, “They’re never going to believe me, are they?”

De Palma: (Laughing) Exactly. Absolutely.

But the formal complexity, the thematic complexity of your work… it’s all there! The critics that don’t get it are the ones that stay on the surface. They’re literalists, and they want everything to conform to everyday logic rather than the sort of dream logic you employ.

De Palma: There’s dream logic, and the other thing that amazes me is that they don’t look at what’s on the screen. That’s sort of being trained by television, where everybody talks everything out to them. I try to tell stories with pictures. I usually have quite elaborate designs, and I spend a lot of time picking these architectural places precisely because they will take root in your subconscious. But the critics sort of dismiss it as nice camera work. (Laughs)

You’re a “cold technician”.

De Palma: Yes. Exactly right. “Manipulative, cold technician.” Well, hey! I’m sorry, but I don’t know too many people who are making those kinds of movies today. I go to a movie, and I sort of visually fall asleep. Nobody seems to think about the way things look, the locations that they pick, or telling stories with pictures. How about that?

I remember Martin Scorsese talking about Eyes Wide Shut upon its release, and he was bemoaning the critical response. They’d forgotten that a shot has value.

was bemoaning the critical response. They’d forgotten that a shot has value.

De Palma: That’s right. Absolutely correct.

And Femme Fatale is another example where I got into an argument with a fellow critic, and he hadn’t even picked up on the clocks. And I’m like, “Really? He kind of spelled that out for you.”

De Palma: It doesn’t move. (Laughs)

Yeah. And somebody could actually make the case that you’re being very unsubtle.

De Palma: “Do you want a little sign?”

With flashing lights?

De Palma: “Look at this! Sleeping woman!”

It is exhausting. And I read folks like Armond White—

De Palma: My defenders. They’re a violent group.

I wrote a series of pieces for Ain’t It Cool News back in 2001 for the American Museum of the Moving Image’s retrospective of your films, and I receiv some… interesting emails.

De Palma: I must say that a lot of the interesting critics are on the web. There was that critic who was on Salon. He was a great defender of me.

Charles Taylor.

De Palma: Yeah. He writes all kinds of cultural things. Fascinating guy. But besides Manohla, who’s a very good critic and whom I read before [she defended Femme Fatale], I’m lost. These critics have been around forever. Thirty years. Isn’t that a little long for a critical run?

And the problem is that a lot of new critics who come along have watched too much television, and don’t really know how to watch a film.

De Palma: Well, I discovered that last year when I was at Toronto talking to kids with Terry Gilliam. [Beaks’ note: Gilliam and De Palma talking to children. This makes me happy.] We were talking about cinema that they hadn’t seen, and they didn’t know what we were talking about – the canvas and composition and stuff like that. I mean, I saw Vertigo at Radio City Music Hall in VistaVision! When I saw the restored version, and everyone was so excited, I was like,  “No, no! You never saw Vertigo in VistaVision!” Projected in VistaVision… it was unbelievable! I saw Barry Lyndon at the Cinerama Dome on a screen so big I just went, “Oh, my god!” These people have never seen these things. I saw Lawrence of Arabia with an overture and intermission. (Laughs)

“No, no! You never saw Vertigo in VistaVision!” Projected in VistaVision… it was unbelievable! I saw Barry Lyndon at the Cinerama Dome on a screen so big I just went, “Oh, my god!” These people have never seen these things. I saw Lawrence of Arabia with an overture and intermission. (Laughs)

And now they try to recreate that experience on DVD, and it’s just not the same.

De Palma: No! You need the size of the screen. Those shots will not work on a screen like that.

And now that the industry is moving towards digital—

De Palma: It’s worse. The wide shots really fall apart in digital. So far.

Are you going to stick with film for the duration?

De Palma: I love the big canvas. Why are there big screens to put things on? To see this movie in Venice and Deauville, it’s just like, “Whoa!” Screens are huge.

One thing I’ve always loved about your movies – and it’s the reason I go back to many of them time and again, especially Blow Out – is the way that you find cinematic rapture in grand tragedy. It’s painful. At the end of Blow Out, we’re devastated. Everything is lost. And yet I find myself watching that movie over and over again. And it’s not like the experience is cathartic. It reinforces a worldview that I have, but… I just wonder where that comes from. It’s like a celebration of pain.

De Palma: Or sorrow. One of my favorite movies is The Red Shoes. It’s beautiful. I like beauty, and I like tragedy. I like to cry and be moved by what happens to the characters. I like Puccini operas. This is the kind of stuff that you never see. You can’t have a downbeat ending like this anymore. And this has been in art throughout the ages. I guess it’s because now you can’t sell products with a downbeat ending. You can’t be depressed, and go out and buy something. I think that’s really the answer to it in a nutshell. You’re not going to be using your credit cards if you’re sad. (Laughs)

And that’s denying one of the greatest traditions of storytelling.

De Palma: Correct. You’re supposed to feel these things, and it’s supposed to bring something out of you. I think it’s great when you cry at the end of a movie. I’m moved at the end of [The Black Dahlia]. When I see Josh looking at Scarlett at the end of the movie, I’m like, “Oh, my god!” The line that came out of improvisation in that scene with Mia [Kirshner], where I’m beating up on her while she’s telling her sad story. And then she suddenly turns to the camera and says, “They said I’m very photogenic.” That stuck in my mind. There was nobody more photogenic than Betty Short. Little did she realize how photogenic she was. And that’s why I save the image of the body for the end, because that’s the photo that you’ll never forget.

When you were approaching The Black Dahlia, and trying to figure out the visual design of it knowing that there was going to be more dialogue than you’ve ever had in any of your movies, did you feel at all constricted?

De Palma: No, because I like to direct other peoples’ material. I have enough obsessions of my own that I can put in my own crazy movies. I like to get away from them. So I’ll make a movie like Mission to Mars just to get into another universe. My fans may not be happy about what I’m doing, but it puts me in a whole different area. Hitchcock used to say he’d go make a well-made play so he wouldn’t have to think about [his obsessions]. Like Rope or Dial “M” for Murder, where he’s on one set and shooting in 3-D, he’s just picking a technical exercise while he’s gearing up for something really big. I always think that’s very important for a director, much I think it’s important for an actor to go onstage and play a classical role… you’ve got to just keep going back to your craft. Be an interpretive director; don’t impose the whole thing on it. And I was very scrupulous in my attention to trying to keep the complexities of Ellroy and the ambiguity in the material. People would say, “Well, wouldn’t it be simpler to…”, and I’m like, “Yeah! It would be simpler, but that wasn’t the way he did it. This is a great book, and I’m leaving it the way it is.”

But Hitchcock was so prolific. He was able to make a film a year, or sometimes more than that. Yet you’ve gone four years in between movies. Is there any frustration that you can’t work more frequently?

than that. Yet you’ve gone four years in between movies. Is there any frustration that you can’t work more frequently?

De Palma: I couldn’t agree with you more. The great directors of the 40s and 50s were making two or three pictures a year. You don’t get better sitting in your trailer thinking about it. That’s true of actors and it’s true of directors.

I’ve never been through this experience before. The financing for this picture fell through twice. I scouted locations for this picture in L.A., Berlin, Rome and Bulgaria. I’ve never been in a situation where you’re starting up, and then all of a sudden the financing falls out and you go home for three months. Then you get a call: “Oh, we got another piece over here. Can you make the picture in Berlin?” I said, “Uh… yeah. Let me see what they’ve got there.” Then that fell apart. “Can you make the picture in Rome?” And that’s how it sort of happened.

The talk right now is that you will make The Untouchables prequel next. The original is one of the few films of yours that was unabashedly commercial. And it’s also one of the few films where I can sense another voice.

De Palma: Yes. I’m interpreting Mamet.

But this script is by Brian Koppelman and David Levien.

De Palma: And rewritten by David Rabe.

Oh, really? That’s great!

De Palma: Well, Art and I were in Bulgaria, and he was working on the script with these two young writers. I said, “What are you doing?” He said, “I’m working on this, but it’s not exactly right.” So I said, “Well, let me read it! I’m sitting here. We’ll have 173 dinners together; we might as well be talking about something.” So that’s how I got involved with it. And then it got quite interesting. There’s an assassination in Tosca that I’ve always wanted to do that I wrote for another script, and I was able to get it into this script. It’s an incredible set piece where they kill [mobster James] Colosimo while he’s watching Tosca, which is something I’ve wanted to do for years. So I’ve got a whole bunch of good ideas. And then we have this whole relationship between the young Sean Connery character and Al Capone with a girl in between them; I came up with this idea of a saloon singer. It’s good.

I love how you have bits that you take from unproduced scripts and insert them into other movies, like the sequence from Prince of the City that you used in Blow Out. It’s like a comedian who mothballs a bit until he can find a place for it in his act. How many of these things do you have lying around?

De Palma: I have them in my computer and in my scripts that don’t get made for one reason or another. In Dressed to Kill, I had the cruising scene where somebody gets picked up in an art gallery, which was from the script for Cruising that I never did.

You also say that you’re seldom at a place where anything you want to make gets made. Are you making these films – The Black Dahlia and The Untouchables: Capone Rising – to acquire a little studio clout?

De Palma: It wouldn’t hurt. I haven’t had a really big hit since Mission: Impossible, and that was ten years ago. You have to make big commercial pictures occasionally. The trouble with my ideas is that they’re expensive. I can’t shoot two guys in a café; that’s not what I do. I need to have a certain amount of commercial success in order to keep working within the system, so I’ll find something that I can bring my visual storytelling to that’s more of a genre picture.

And maybe in the future go back to deconstructing genre like you did with Femme Fatale?

De Palma: You can’t get any crazier than Femme Fatale! I enjoyed making that movie. I was living in Paris, I was running around on my scooter, I had found all the locations and the  financing…I had never done any of that before. It was exhilarating to me. I had an idea for this collage that was kind of weird. I mean, you make a movie in which somebody’s asleep for half of the film and it’s all a dream, somebody’s going to start throwing beer cans at the screen. (Laughs) It was so funny when I was talking to Antonio; he had all these ideas about the character that he was playing and what he was doing. And I went, “Wait a minute. You don’t quite realize that you’re just her dream character. Everything you do is because she’s dreaming you doing it. It has nothing to do with you. You’re this guy on a balcony taking a picture of this square because you’re trying to look for the image that’s going to complete this. That’s all that you are in reality.” He was a little confused by the material.

financing…I had never done any of that before. It was exhilarating to me. I had an idea for this collage that was kind of weird. I mean, you make a movie in which somebody’s asleep for half of the film and it’s all a dream, somebody’s going to start throwing beer cans at the screen. (Laughs) It was so funny when I was talking to Antonio; he had all these ideas about the character that he was playing and what he was doing. And I went, “Wait a minute. You don’t quite realize that you’re just her dream character. Everything you do is because she’s dreaming you doing it. It has nothing to do with you. You’re this guy on a balcony taking a picture of this square because you’re trying to look for the image that’s going to complete this. That’s all that you are in reality.” He was a little confused by the material.

“You’re stuck in a genre archetype’s existential crisis.”

De Palma: (Laughing) Yeah.

I love it when you make those films. Raising Cain is the one that first got me in trouble with my friends.

De Palma: Isn’t that the nuttiest movie? The interesting thing about that movie is that I could not make the beginning work, and it drove me crazy. The idea essentially came from an experience I was having. I was having an affair with a married woman. She used to come over to my house before she went home, and we would make love. Then one time she fell asleep, and I thought, “What would happen if I didn’t wake her up and she slept through the night?” That was what I always wanted to start the movie with – that, and her dilemma instead of with the Lithgow story. But I couldn’t make it work. It drove me crazy. I thought it was such a great idea.

You think these movies through so thoroughly. You talk about how you want them fully thought out before you go and make them, but those movies are so incredibly rewarding. I know they drive people nuts (De Palma laughs), but you have to engage the movie at its level and interpret it in the correct framework. And, again, I think those movies work beautifully in a formalist framework.

De Palma: The concept of Raising Cain is fantastic. The idea that every time you have some traumatic event in your life you create another personality so you forget it happened to you… I mean, what a great idea for a movie!

But these movies are very mischievous, too.

De Palma: They’re very original, there’s no question. Even though they’re supposed to be Hitchcock rip-offs… (Laughs).

Can’t ask for a better end to the interview than that. Please go see The Black Dahlia on September 15th so I can see more Raising Cains and Femme Fatales.