Fantastic Four #600 (Marvel, $7.99)

By Jeb D.

The “superhero-death-and-resurrection” playbook tends to focus on one basic narrative: a year or so is spent mulling over the implications of loss, often with one or more characters attempting (unsuccessfully) to fill the shoes of the fallen; ultimately, the didactic tale “teaches us” that the world needed the departed, a realization that comes just as the fallen hero returns to set things right. Now and again someone works a worthwhile variation on this-in Ed Brubaker’s hands, Bucky Barnes carried on a Captain America series that never violated Cap’s basic principles while becoming very much its own story-but the typical storyline is more about the absence of the missing character than about those left behind moving forward.

Not surprisingly, when Jonathan Hickman was handed the responsibility of offing the Human Torch for yet another round of mainstream media coverage, he didn’t so much reject the playbook as continue to write as though he’d never heard of it. During the past year, he’s built up the “Future Foundation” into the most extended version of the FF family yet, including Dragon Man, Reed Richards’ father, alternate Reeds from other universes, and a clutch of superkids; he’s followed the meandering path of the refugee Reeds and such familiar faces as Ronan the Accuser, the Kree Supreme Intelligence, and the Inhumans. He’s shown the complications in Reed and Sue’s relationship—he’s neither interested in simple lovey-dovey or in cliche marital spats—and brought Spider-Man onboard, only to take him out of his familiar costume and sideline him for most of the duration. What he’s hardly done is spend much time wallowing in the death of Johnny Storm. The plot of the “four Reeds” continued from the pages of Fantastic Four, and two out of the 11 issues of FF so far published were devoted solely to the Inhumans. In fact, the principal effect of Johnny’s loss seems to have been to get Ben Grimm largely offstage, moping over what his friend’s death has done to the FF and his place in it.

Thus, the return of Johnny Storm (oh, sorry-SPOILER!) will have the opportunity, not simply to help Johnny realize “his place” in the Marvel U, but has the potential to be the spark (so to speak) that re-ignites Marvel’s first family back to the flagship status it long ago surrendered to the X-Men, and now the Avengers.

Or maybe not. That may not be Hickman’s purpose: he seems perfectly happy to continue weaving story threads from Kree invasions to the return of the Inhumans to reinvigorated versions of such FF standby villains as Galactus, the Mole Man, and Annihilus into an epic rivaling Marvel’s recently revived “Cosmic” titles. I tend to assume that the upcoming division of the storyline between two regular series (a revived Fantastic Four and a continuing FF) will bring greater focus on old-school “Flame On” / “Clobberin’ Time” adventures, but there’s nothing in this generous 96-page volume that suggests it. Instead, Hickman and his collaborators have put together a five-story mosaic that provides context to the return of Johnny Storm, without deviating from the ongoing, entertaining yarn he’s been spinning for the past couple of years.

Hickman opens things with regular artist Steve Epting, tossing in backstory for anyone who quit reading when the title was shortened and renumbered. Earth is caught in a pincer attack between Kree on the one hand, and the Inhumans on the other, with the Supreme Intelligence pulling strings in the background. While the Avengers join forces with the FF to face the invasion, Nathaniel Richards, and the last surviving alternate Reed, with his captive Victor Von Doom, confront Doom’s adopted son Kristoff, in search of a power to turn the tide. It builds to the “big reveal.” From there, artist Carmine di Giandomenico takes over, turning a familiar “hero forced to fight in the arena” tale into something of otherworldly beauty, while Hickman’s script is so rich in observation and insight that it’s obvious he’s just been chafing at the bit to bring back a character he clearly knows very well. Calling this segment the high point of the book isn’t to suggest by any means that the remaining stories take things downhill: Ming Doyle brings a 60’s Ditko vibe to a tale of psychic connection between Black Bolt and Medusa; Lenil Yu calls back to Matt Fraction’s The Mighty Thor while Hickman brings out the frightening grandeur of Galactus; and Franklin and Leech get the last word as Farel Dalrymple and Lovern Kindzierski’s rough, cartoony art help Hickman sum things up with a story that’s funny, ominous, and an indication that the grand epic isn’t going to slacken in its newly bifurcated version. And less than a dime a page.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Diablo #1 (DC, $2.99)

Diablo #1 (DC, $2.99)

By Adam Prosser

Of all the people I know of my generation, I’m probably the least interested in video games. It’s not that I don’t see the appeal; just the opposite, really. I just tend to be both obsessed with my hobbies and a huge procrastinator, and there just came a point where I realized that if I ever wanted to get serious about comics I’d have to leave games by the wayside. (Also, as expensive as comics can be as a hobby, they’re nothing compared to the expense of a video game system.)

So I know almost nothing about Diablo, and am going into this comic totally blank, which seems like a good state of mind in which to review it. Comics do have to stand up on their own, after all, even when they’re adapted from another source. And I have to say, this one does an admirable job of it.

Diablo is a fantasy epic about a world called Sanctuary, apparently created to be a neutral zone between angels and demons, with mixed results. We open on a time which I’m guessing comes quite some time after the various games, judging from the in-depth exposition on the first two pages, delivered by a beggar with mystical abilities who’s just attempting to make a few coins by telling stories. The beggar gives the hero, a man called Jacob who’s on the lam from the local authorities, the standard spiel about destiny before, less predictably, swiping his sword to hock for money and leaving him to stumble unarmed across a desert. There, Jacob finds a mystical cave filled with carvings that do indeed seem to predict a grand destiny for him, spelling out his past and future, and informing us how he got to this point.

I’ve always had an essential love for the genre of epic fantasy, but I’ve also been disappointed over and over again by many of the actual stories produced in that genre. They tend to ponderous world-building and self-importance, not to mention needless bloat; this is, after all, a genre where every book seemingly has to be part of a trilogy (or quadrilogy, or pentology…) Which wouldn’t be so bad if so many didn’t seem to see characterization and plot as an afterthought, usually just plugging a few details into the standard hero’s journey, wrapping it in Tolkienian structure, and calling it a day.

Diablo #1 doesn’t exactly smash that mold in the way that the truly great fantasy books and comics have done, and in fact the basic setup here is pure Joseph Campbell so far. Yet I really enjoyed this comic, mostly because Williams has a deft and elegant handle on storytelling, as with the interesting ways of delivering backstory mentioned above, and enough quirk and substance in the characters to effortlessly draw me in. By the end of the comic, I have a good sense of who Jacob is and why he’s being pursued, which is more important than establishing the cosmic stakes—though Williams hints at that, as well. Meanwhile, artist Joseph LaCroix, with the incomparable Dave Stewart on colours, creates an immersive and interesting world, an essential ingredient for any fantasy comic, through his “sketchy Mignola” style artwork.

It’s possible that I’m missing out on a lot of fun Easter eggs that any fan of the Diablo games would be better able to appreciate; it’s also possible that this comic would outrage fans of the games with the deviations from the mythology. I’ll rely on commenters below to set me straight. But from a newbie’s perspective, this is a very well-done comic that’s accessible and entertaining for anyone.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

The Extraordinary Adventures of Adèle Blanc-Sec Vols. 1 & 2 (Fantagraphics, $24.99 each)

By D.S. Randlett

If this title, written and drawn by Jacques Tardi, has one true main character, it is the city of Paris. The city has two faces, the familiar one that Tardi painstakingly and beautifully captures in his illustrations, and the shadowy and surreal one wherein lurk the many absurdities that the title character encounters. The “real” Paris is drawn with the weight of history behind it. Not only the history that belongs to the generals and the Revolution, but to the waddling feet of every day (possibly overweight) Parisians. In Tardi’s universe, the Paris of historical grandeur and small pleasures is actually a kernel in a vast universe defined by absurdity.

First, there are the people who run the place. The police department of this version of Paris is defined by its willingness to promote the corrupt, and its top to bottom ineptitude. The underworld is defined by a similar ineptitude, as well as a reliance on the supernatural to carry out their various schemes. A psychically controlled Pterodactyl toddles out of an egg after millenia of dormancy. Demons stalk the Eiffel tower while a cult lurks in the (deeply absurd) Paris underground. A caveman and later a mummy are resurrected to serve some dark purpose, only to prove far too civilized for such business.

And then there is the heroine herself, Adèle Blanc-Sec. She’s a rogue in every respect, belonging to none of Tardi’s worlds. She’s beautiful in the aloof, bemused way of Isabelle Huppert’s character from “I Heart Huckabee’s”. Without the nihilism, of course. Adèle moves through the various intrigues of this series with a uniform expression like she’s waiting for something to really happen while commenting on the ridiculousness of everything happening around her. Which brings us to the book’s major problem.

This series is a parody of the adventure genre, and every character is meant to stand in and poke fun at a certain genre trope. This in itself is nothing to be concerned about, but the best parodies still have characters. Think Frank Drebin. While Police Squad is a parody of the cop show, and The Naked Gun is a parody of the action film, Frank still has identifiable character traits. While they may not be very many, he’s more than just a joke machine, he has desires that drive him through the story. So far, there’s none of that in this series. Almost every character is a complete cipher, even Adèle herself seems to be there to simply voice Tardi’s own observations about the genre (she talks a lot about how she’s sick of complicated plots). Instead of the characters driving the plot, it’s the other way around. This may be a stroke of genius in a way, an observation on the absurdity of plot itself, but it doesn’t make for particularly satisfying reading.

The story is not without its moments, though. The awakening of the caveman is chuckleworthy, and the revelation of what mummies really are is a riot. Tardi’s art is just simply amazing, and is worth the cover price alone. But on the whole, these first two volumes feel like the work of a master that aren’t themselves particularly masterful. I will continue to read this series as Fantagraphics releases it. As Volume 2 draws to a close, the final panels reveal the coming of one of mankind’s greatest absurdities, and with it the series begins to display some ambition. How will the First World War affect Paris’ absurd underground? Will The Extraordinary Adventures of Adèle Blanc-Sec have more to offer going forward? If the story can manage to catch up to Tardi’s art in future volumes, I will be greatly impressed.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

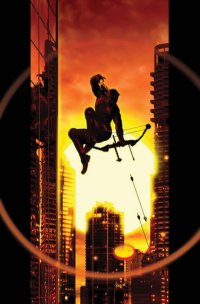

Ultimate Comics Hawkeye #1-4 (Marvel, $3.99 ea)

Ultimate Comics Hawkeye #1-4 (Marvel, $3.99 ea)

by Graig Kent

The Ultimate Comics line is a tangent from the main “616” universe, a variation, familiar but not the same. Though striving to be its own “universe”, diverging further and further by killing off big name characters and fudging the status quo of some of Marvel’s biggest brands, it’s still perpetually living in the shadow of 50 years of publishing history. As a result there’s a ever-present need for readers to orient themselves in the Ultimate books by looking back to what has come before, not in the Ultimates line, but major and minor stories, events and characters of decades past.

The Ultimate Comics Hawkeye mini-series exists as a B-story to the current Ultimates storyline, something that would have developed in the same book back in the days when there were five or six more pages of story per monthly issue. Of course, here the writer of both books, Jonathan Hickman, uses the space to turn a sideline into a mainline story, only to truncate the endgame with a “continued monthly in The Ultimates” (which is code for it’ll pick up again… down the road… eventually… maybe).

The book delves peripherally into Clint Barton’s relationship with Nick Fury (including the origin of their bromance, if you will), which is a Picard and Riker kind of deal, chummy but still chain-of-command. Fury relies upon Hawkeye as his “Number one” and trusts him to get any job done, mainly because he always has in the past. The main stage however finds Hawkeye leading a team into SEAR (South East Asian Republic) where a superhuman weaponization program has backfired on the government (as these things so often do) and now a group of chemically transformed citizens over 100,000 strong not only usurping the powers-that-be but also offering transformation and citizenship to the world. Hawkeye is the world’s foremost marksman and capable of turning almost anything into a weapon, but even he knows he’s in way over his head. His task however is not to cease the conflict but to retrieve The Serum for use by SHIELD. Armed with Ultimate X to assist and The Hulk as a distraction, what Clint Barton ultimately finds is certainly not what he expected, less conflict, and a new world power manifesting that has equal opportunity of being mankind’s salvation in the form of the Eternals, or its downfall in the Celestials.

Obviously those names sound familiar, and Hickman is additionally using elements of Grant Morrison’s New X-Men run (including no just one, but two new iterations of Xorn) (and perhaps even drawing from Warren Ellis’ inaugural story in The Authority, “The Circle “) so throughout one’s mind keeps wandering to stories, situations and characters past. Which isn’t to say that what Hickman is doing is hack, quite the opposite, it’s a pretty great read with some excellent ideas that could have a monumental impact on a universe which, unlike most, isn’t opposed to drastic change. Hickman excels at providing “thinking man’s” superhero comics, and here opts to wrap up the series with concepts and conversation instead of an action climax, yet manages to make it riveting and intense, lessened only by the distraction of the familiar.

The art from Rafael Sandoval and Jordi Tarragona features crisp, tight lines keeping the pages tidy amidst the plentiful detail Sandoval packs in. Sandoval’s Hawkeye is a dexterous, agile and nimble fighter, as illustrated through numerous action sequences where Barton finds himself contorting through a hail of gunfire and laserbeams. It is and action-heavy mini-series, but as I noted the fourth installment is largely comprised of talking heads or flashback montages, and Sandoval negotiates them nicely. If there’s any negative to his work, it falls under consistency, mostly in the faces, as they morph awkwardly between panels, emotionally expressive but inconsistent and off-model.

If you’re reading The Ultimates, this is a must read right alongside it. It’s intriguing enough on its own, but I find it harder to recommend it if you’re not sticking with Hickman’s other journey.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

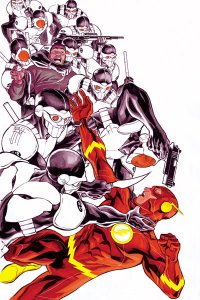

The Flash #3 (DC Comics, $2.99)

By Bart Bishop

Let’s get this straight: Wally West is my Flash. I grew up with the character, having read bits and pieces of Mark Waid’s run, Grant Morrison’s, and then Geoff Johns’. Sometime around Infinite Crisis, however, the character ran out of steam. He was married and with kids, and what had previously made him fascinating (a public identity, emphasis on the bizarre sci-fi aspects of the Speed Force) had been discarded. The years that followed, with Bart Allen taking up the mantle and Barry Allen returning, have not been kind to the Flash franchise as a whole. Over all there’s been solid writing, but the corner DC allowed Johns to write them into was unacceptable. Before the New 52 relaunch, there were three guys running around named The Flash, two of them with almost identical outfits, and the title was suffering from over-saturation.

With that confession in mind, it’s clear that this new series was ice skating uphill to convince me that Barry is a character worth following. Written by Franchis Manapul and Brian Buccellato, with art by Manapul, issue #3 cements that this is an entirely fresh, provocative take on the character and title as a whole. It helps that this Barry is younger and unencumbered by baggage (no marriage, no children from the future), but he’s also a bit of a geek. This is appropriate, as the Barry of 1956 was a comic book geek (he named himself after reading old Jay Garrick comics). It’s obvious that Barry is book smart and good at his job as a forensic scientist, but he’s also clever. The fastest man alive shouldn’t just be a brawler; he should be able out-think his opponent and come up with the most non-violent solution possible.

Issue #3 deals with just that, putting Barry into an impossible situation and forcing him to save the day. Opening with the fallout from last month, as an EMP has been unleashed upon the city by new villain Mob Rule (actually Barry’s old friend Manuel) and Flash has to handle out-of-control cars, trains and even a swan diving airplane. Meanwhile he’s still learning how to deal with his new super brain, which can consider multiple possibilities simultaneously, in a way giving Barry the ability to predict the future and act accordingly. This is a very clever plot device, working like Final Destination in reverse, that conceptualizes Flash’s powers in a completely understandable and gratifying fashion. It runs a risk of alienating the audience, however, by turning Barry into something post-human, but so far writers Manapul and Buccellato have managed to keep him grounded with heart and relatability.

The strongest bit of characterization is the use of “Flash Facts” at the beginning of this issue. Flash Facts are a long-standing tradition of the Barry Allen character, and Manapul and Buccellato use this technique to strong effect by having Barry’s inner monologue about why he doesn’t drink coffee. Not only does he provide a nice bit of trivia, but also a naturalistic opportunity to explain his lesser known powers: the vortexes and vibrating through solid objects. This sets up a spectacular visual of an airliner passing through a bridge. The rest of the supporting cast is slowly being built up, like Patty the brainy lab technician (and possible love interest) and Forrest the detective. They’re all funny and engaging and most importantly noble; these are characters that smile and do good for goodness’s sake, and that’s refreshing in 2011 when entertainment media , and the world, is so full of darkness.

I’m also enjoying the development of “The Gem Cities”, Keystone and Central. Prior to the New 52 relaunch they were situated in the Midwest and were known for their automobile industry. Now, well, I’m not sure where they’re supposed to be as they’re surrounded by desert badlands, but it’s clear that the cities are just important of characters to Manapul and Buccellato as Barry and the rest. Those badlands do lead to an odd moment, however, when new character Dr. Darwin Elias drives out to meet with the Trickster about a tank that’s apparently important over in the Captain Atom monthly. This scene is incredibly clunky, as it fails to introduce the Trickster (he’s called Axel, yes, but I recognized him from his pants) and relies on knowledge of another comic book. Speaking of Rogues, Captain Cold is reintroduced when Iris West goes to Iron Heights Prison to interview him, and the prison has broken out in a riot due to the EMP. What would seem to be an urgent plot point, a possible prison break, only warrants one page. I’m assuming this will come into play next issue, but it could’ve used more attention here.

The art very cinematic, and yet is able to do things movies can’t. As Manapul is the artist and Buccellato is the colorist, and they both double-duty as collaborative writers, there’s a collision of storytelling where both the writing and the art are equally as important in conveying the narrative. Manapul has a cartoony style but gives all the characters distinct looks and expressive faces, with modern fashion sensibilities and haircuts. Buccellato’s colors, meanwhile, have a water color like softness to them that lends a constant sense of movement and speed as lines blur together. I love how the title page incorporates The Flash into the airliner, along with the multiple threats (both the passengers of the jet and the drivers on the bridge) he faces. Very Will Eisner-esque, as well as incorporating sound effects into the physical space of the action such as water splashing in the first issue.

The cover, by Manapul, isn’t as effective. It shows Barry being swamped by dozens of identical clones of his friend Manuel, current antagonist Mob Rule. Although this is evocative of the nature of the plot, Flash being overwhelmed by Mob Rule’s machinations, it’s not as intriguing as previous covers. It isn’t as bizarre as the cover of #2, showing Barry’s neurons firing as he tapped into the other 90% of his brain, and #1 with Barry in the dynamic yet classic new suit design (it’s a little too busy for my taste, the lightning channeled through the costume’s seams is an eye-catching effect) racing towards us with an electric depiction of speed and scale. Mob Rule himself is a bit of a generic physical presence, as he looks like any other technological ninja running through a comic book (not all that different, for instance, than Nobody over in Scott Snyder’s Batman). The lack of background, with Flash and Mob Rule falling through white space, could have been used to better effect; possibly implying a lack of safety net or downward spiral for Flash in handling the situation. Instead it’s just…there. It’s stiff and cluttered, unlike the art inside the book.

The Flash is the best title DC is putting out at the moment. It’s fun, it’s exciting, and it’s pushing the boundaries of the medium. This is the next natural evolution of superheroes, which is appropriate considering how Barry ushered in the Silver Age.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Superior: KAPOW! World Record Special #1 (Marvel, $2.99)

Superior: KAPOW! World Record Special #1 (Marvel, $2.99)

by Graig Kent

Mark Millar is a man of modest talent and great hubris. He is a shameless self-promoter, outspoken, a loudmouth, and an all-around devious character, all part of a cleverly cultivated personality that is a large part of what made him the A-list name he is today. He gets attention by being a polarizing figure, in both words and in action, having his firmly entrenched fans as well as his adamant detractors sally back and forth about the merits of his work and his public persona, all the while drawing more attention and sales to his projects, if as much as curiosities as art (I doubt Millar cares either way).

In this regard, Superior: KAPOW! World Record Special is patented Millar all the way. It’s a freakshow curiosity, it’s attention-getting, it’s controversial, and most of all it’s ego buffing. With this book Millar has corralled dozens of illustrators each taking on a panel a piece (most are industry folks, including Dave Gibbons, Jock and Frank Quitely, but some are Millar’s fans) working off a hastily constructed script (servicing a 20-page book with about 4 pages worth of actual story) to give the book the Guinness World Record for “fastest production of a comic book” (11 hours, 19 minutes, 38 seconds) and “most contributors to a comic book”.

The “story”, as it were, is about a woman wishing aloud to the Superman analog of Mark Millar’s creation to perform the frivolous task of finding her infant daughter’s beloved lost toy. The pages are largely filled up by the numerous things Superior does around the world (and in space) to help mankind, but ultimately able to come through for the distraught mother in the end (spoiler alert!). It’s a puffy, frivolous, unimaginative, trite waste of time as far as a story goes. If it gets interesting at all it’s in trying to determine which creator did which panel (although figuring out all of them, given the participation of fan who are quite clearly not professional illustrators, is a futile effort). Despite the names involved, most of the artwork is rushed and choppy, as well as shoddily reproduced (the book looks like it was printed from gif images scanned in at 72dpi).

A Millar defender might say “it’s all for charity” as if charity somehow excuses poor quality (well, I guess people generally do buy grocery store generic for the food drives don’t they, so perhaps it does). The charity angle is a nice, but once again, attention-getting gesture on Millar’s part with “a portion of all proceeds” from the book’s sales going to the Yorkhill Children’s Foundation (and a page of space providing more details on the foundation at the back). Of course, how charitable is it when the print run was capped at 10,000 copies and retailers were shorted copies of their order, thus depriving some fans of the comic and the charity of any additional proceeds? It has, however, become an instant collector’s item, if that sort of thing really means anything anymore.

In the end, the whole endeavour leaves a bit of a sour aftertaste. It’s a poor end product that dubiously supports charity openly, while in actuality is really only supporting the aggrandizing of Mark Millar’s ego. Well played.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars