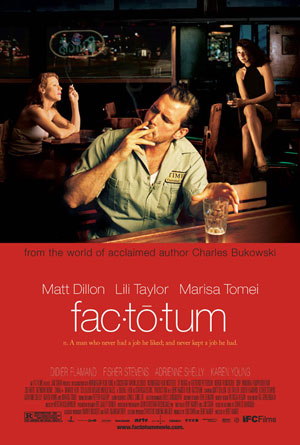

Matt Dillon wants to be taken seriously. At the New York press day for his new film, Factotum, he was very interested in talking about the ins and outs of his character, Hank Chinaski, the alter ego of sodden writer Charles Bukowski. He wanted to talk about how he inhabited the character, how he did the research, how he tried to create a complete person on screen.

Matt Dillon wants to be taken seriously. At the New York press day for his new film, Factotum, he was very interested in talking about the ins and outs of his character, Hank Chinaski, the alter ego of sodden writer Charles Bukowski. He wanted to talk about how he inhabited the character, how he did the research, how he tried to create a complete person on screen.

You can’t blame the guy for wanting to talk about his craft – with the Oscar nomination for Crash he’s seen his career resurging, and he’s being looked at in a way very different from his years as a Tiger Beat heart throb or as a one-foot-in-the-wilderness working actor in the 90s. Factotum is based on a couple of Bukowski novels, and as is usually the case with Bukowski the story is about a man who drinks too much and the screwy, often fucked up world he lives in and makes for himself. It’s the kind of role actors like to sink their teeth in, especially handsome actors. Handsome actors love to get ugly for roles.

A factotum is someone who holds many positions, and in the film Chinaski holds many different jobs, mainly because he just can’t keep them. As he stumbles drunkenly from shitty gig to shitty gig he writes stories and novels, hoping to one day get published. Along the way he runs into equally ruinous women, one of whom, Jan, is played by Lilli Taylor. Jan and Chinaski have a truly bizarre scene together involving crabs, genital burns and gauze.

Factotum, directed by Bent Hamer, opens this weekend in select cities.

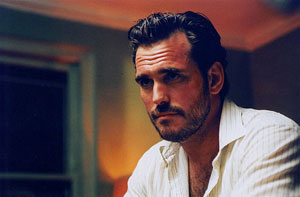

Q: Hank Chinaski isn’t looking that great in this film. How did you change yourself to play him?

Dillon: Well, you know, I grew the beard obviously. The hair was done a certain way. I shaved my hairline back a little bit, just a little bit. I let myself go, I put on some weight. I didn’t come up with, “Oh, I’m gonna put on thirty-five pounds for this part.” You know you hear about actors “Oh, I put on forty pounds for the role.” I don’t know how much weight I put on but I put on a little weight. But more of it for me was in the behavior; you know, in the physicality of the behavior. So that was the feeling I had, like he was a guy who was physically defeated. You know what I mean, like the way he carried himself physically was that the material world had sort of defeated him. He surrendered to that, but yet he was very bright, and very sharp and was very strong mentally. But there was this other side to him, you know, and this kind of the way he carried himself and that really comes right from Bukowski. I mean what I had seen of Bukowski, that’s what I got from him. This kind of this defeated effortlessness.

There was something that I heard – I didn’t see it but it was written on his tombstone, the words “Don’t try.” And that really helped me. That really helped me with the character because, you know, he doesn’t try to live up to what his father wants him to be. He doesn’t try to fight for his job. He doesn’t try to stop drinking. He doesn’t try. The only thing he really tries to do is to get published as a writer, and that finally happens at the end, but he’s not even aware of it; he’s not even there to partake in it. But that was really helpful to me with the character.

I spoke to Linda Bukowski, his wife. She said that Bukowski felt misunderstood and what really bothered him was that he was often depicted as dirty, as kind of a slob, like physically. Unwashed. It really bothered him. She said he was very neat, he was very – you know, he was certainly disciplined as a writer, he was very disciplined in that way, so it was a sense of order with him. And yet I also knew that what she said about the clothing wasn’t important but at the same time it was very important for him to keep himself together in that way. That really helped me, that really, because I think as an actor the first impulse you might have is, if you want to play a skid row bum – at times he was homeless in the film – you would like rub your face in the grime and get down in the gutter, that’s the natural inclination. That’s what you typically see and that’s the first instinct of the actor, but here it’s really, he’s the antithesis of that. I mean, yeah, he is all those things, but he still manages to kind of keep himself, get up and comb his hair, get dressed mostly.

Q: How did you sell yourself to Bent – he’s said you were too handsome for the role. Dillon: Well, everybody’s too handsome compared to Bukowski. I didn’t have to convince Bent at that point, maybe that was something between he and [producer] Jim Stark; I don’t remember it that way. I think by the time we met he wanted me to do the picture but maybe he had his own struggle with that before he got to that point. For me, I felt pretty much the way Bent felt, not that I was too handsome, but that I wasn’t really physically right for the part, so when they approached me about it I was like, “Are you sure you got the right guy?” [But] once it was made clear that I wasn’t expected to become Charles Bukowski I felt much more comfortable. You know, that he had this alter ego called Hank Chinaski; for whatever reason he created this alter ego. I said, “Oh, ok, well that’s a rationalization, you know, that works for me.” It gave me a sense of relief. As long as I don’t have to do an impersonation of Bukowski I’m ok. Then I could go about preparing to play Chinaski. So then Bent and I are walking in Central Park talking and we had something to talk about I didn’t have the answer. He didn’t have the answer and he said, “Let’s call Linda.” We called Linda Bukowski and started to talk about the alter ego. She’s like, “Oh it’s very autobiographical. You have to know.” I’m like, “Oh great.” So now again all roads lead back to Bukowski! So inevitably although I didn’t want to set out to do any kind of impersonation, which I don’t think it is at all, because I really think I worked from the inside out, still it all goes back to Bukowski. So I studied him and I saw footage of him.

Dillon: Well, everybody’s too handsome compared to Bukowski. I didn’t have to convince Bent at that point, maybe that was something between he and [producer] Jim Stark; I don’t remember it that way. I think by the time we met he wanted me to do the picture but maybe he had his own struggle with that before he got to that point. For me, I felt pretty much the way Bent felt, not that I was too handsome, but that I wasn’t really physically right for the part, so when they approached me about it I was like, “Are you sure you got the right guy?” [But] once it was made clear that I wasn’t expected to become Charles Bukowski I felt much more comfortable. You know, that he had this alter ego called Hank Chinaski; for whatever reason he created this alter ego. I said, “Oh, ok, well that’s a rationalization, you know, that works for me.” It gave me a sense of relief. As long as I don’t have to do an impersonation of Bukowski I’m ok. Then I could go about preparing to play Chinaski. So then Bent and I are walking in Central Park talking and we had something to talk about I didn’t have the answer. He didn’t have the answer and he said, “Let’s call Linda.” We called Linda Bukowski and started to talk about the alter ego. She’s like, “Oh it’s very autobiographical. You have to know.” I’m like, “Oh great.” So now again all roads lead back to Bukowski! So inevitably although I didn’t want to set out to do any kind of impersonation, which I don’t think it is at all, because I really think I worked from the inside out, still it all goes back to Bukowski. So I studied him and I saw footage of him.

But that was a tricky balance, you know. A lot of the stuff he did I felt was, there was a little bit of an affectation – like a lot of the poetry readings, and this was no crack on Bukowski, but he didn’t like doing these readings. There was kind of an affectation he had in his delivery, which I think there’s a little bit of that in this its more with the poetry. It’s more with the poetry stuff but that was the type of thing I wanted to capture, because he has that sing-song quality. His voice is very different than Chinaski for the most part. He’s got that kind of high almost feminine sing-song thing, which is strange because when you read him he sounds like, you know, Warren Oates or something, or Lee Marvin.

Q: You’re so good at these scoundrel type roles. What draws you to these kind of womanizing parts and the dark side?

Dillon: Well, whatever it was that drew me to it is probably the same thing that drew me to read Bukowski when I was in my early twenties in the first place. It’s that I like that type of stuff. I think what I really like most about Bukowski is his honesty, you know. He’s really truthful, he just lays it out there. He sees things that nobody else sees. I think for me what I liked about it was the ups and downs of his life. I like that kind of thing. I like that kind of character, you know, I like conflict; drama’s conflict and if you don’t have that in the character it’s really not a worthwhile role to play for me. I like a challenging role and often those characters are.

You know, I don’t know if I would see Bukowski as so dark. I think his view of the world is a fun view. He looks at the humor, he sees the humor of things. He’s able to laugh at himself and the world around him, and I think that’s what I loved about him; I would often wish that I could see the world like that a little bit. To be able to laugh in the worst of situations… I can never forget when I was reading Ham on Rye, when he was laying in bed and that’s when he had that horrible acne when he was a kid and he overhears the doctor saying, “Jesus, this is the worst case of acne I’ve ever seen in the history of Los Angeles.” And [Bukowski] goes, “Doesn’t this asshole realize that I can hear every word he’s saying?”

But I always like the way he speaks. He speaks plainly. So I do think that it is connected with maybe a certain throughline in my career, which is like maybe the first movie I did, Over the Edge, Drug Store Cowboy, maybe the film I directed and this one and a few other ones along the way. And then there’s this other comedy thing. You know other sort of mainstream kind of things I did too.

Q: So much of this film is about making a living. What’s the worst job you’ve ever had?

Dillon: Well, you’re asking a guy who started acting at age fourteen so I didn’t have too many jobs before then. I mean I did work a job while I was acting. One early on because I didn’t have any bread and it was like I was loading trucks at a nursery, a plant nursery place and it sucked. The woman was horrible; she always managed to cut down your salary. It was really horrible and they worked my balls off at that job. I didn’t stick around too long needless to say.

many jobs before then. I mean I did work a job while I was acting. One early on because I didn’t have any bread and it was like I was loading trucks at a nursery, a plant nursery place and it sucked. The woman was horrible; she always managed to cut down your salary. It was really horrible and they worked my balls off at that job. I didn’t stick around too long needless to say.

Q: How did you convince her to hire you? What did you have to say to get the job?

Dillon: I didn’t have to say anything because I didn’t want the frigging job.

As an actor, it’s not the horrible jobs you have to do, it’s like when is the next job gonna come. At a certain level you’re going like, “Jesus man, if I don’t get a good script soon, I’m gonna have to do this slasher movie.” You know what I mean. There is a little bit of that.

Q: It’s rare when a child actor makes it, and it’s even rare for someone who started out at 14 to get where you are today. I don’t know if a lot of people who saw The Outsiders would have imagined your career. Do you ever look back at it, and what do you think about the ups and downs?

Dillon: You know, I don’t try to figure it out too much. I just keep moving ahead and the only thing I’d say about it is that I was young so to me I look at it and say, ‘Wow.’ I was pretty green then. I look back at things and say, ‘I would have done that differently,’ but that’s the old hindsight is twenty-twenty kind of thing. I don’t really know. I don’t really dwell on it that much; youlearn from your mistakes and move ahead. I don’t really think too much. I don’t hang onto the past very much.

Q: Are you going to be directing anything?

Dillon: Eventually I’d like to be. I don’t have anything in the, I don’t have anything that’s, you know, in pre-production now or anything like that. I really think I should direct again. Not that I should but I know that it will make me feel… I really had a great experience doing it.

Q: There’s a scene in the film where you slap Lily. Were you ever concerned about having that scene in the film?

Dillon: At one point they talked about her slapping me. I thought, “Nah, that’s not Hank! That’s not Hank.” But, I think that’s part of the flawed nature of who that guy is; the dichotomy. I mean on one hand he’s this poetic guy who wants to be a writer. On the other hand, you know, he’s this flawed alcoholic drunk and they have this totally dysfunctional relationship. She provokes him, right, in that other fight. They have this thing. She’s tough, she’ll go right up against him too. It’s sort of like one of those crazy relationships. It’s inexcusable that he does it… but he forgives her too, for giving him crap!