It’s hard to think of a better week than the one that began just before and ended right after this year’s Comic Con. It was an unbelievable eight or nine days where I was able to conduct some of the best and most interesting interviews of my career and meet some of the most amazing people I have met in my life. And the capper to all of it was a couple of hours spent with Guillermo Del Toro in Los Angeles.

It’s hard to think of a better week than the one that began just before and ended right after this year’s Comic Con. It was an unbelievable eight or nine days where I was able to conduct some of the best and most interesting interviews of my career and meet some of the most amazing people I have met in my life. And the capper to all of it was a couple of hours spent with Guillermo Del Toro in Los Angeles.

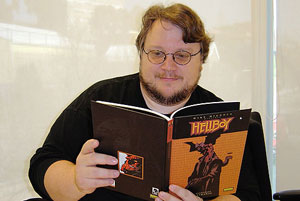

Guillermo had been in San Diego (he told me that his second day at the Con was always his best – people stopped mobbing him on the Con floor after the first day and he could get some shopping done) but we hadn’t been able to meet up. He wanted to show me Pan’s Labyrinth, his new film which is getting raves from literally everyone who sees it, but I had to get back to New York. Instead we met at Meltdown Comics to hang out.

Shopping with Guillermo at Meltdown was a fascinating experience. A couple of people introduced themselves to him, but everyone was very cool and low key. Guillermo hit every single section of the store, and he picked up enough stuff to keep me busy for the next month and a half. He’s voracious with comics, and he loves them from every nation on Earth and in every possible genre and style. And he’s an inveterate collector – he showed me one series of graphic novels that he has collected in its entirety in a number of languages. They were out in new editions, so he bought those as well. We also discovered that we have a favorite magazine in common, the excellent Fortean Times. We both had stopped our subscriptions, though – half the fun of the magazine is finding it on the stands.

While we walked around the store he let me look at his diaries. The word diary doesn’t do them justice – they’re like ancient codexes. He found ten leather bound blank books in Venice years ago, he said, and he’s been filling them with daily observations and ideas and drawings since. Guillermo told me he’s not much of an artist, but the drawings in the diaries proved that he was just being modest. He showed me the first drawing of the mandible-mouthed vampires from Blade II and the watery ghost from Devil’s Backbone. He showed me concept art for Pan’s Labyrinth, and some drawings that hadn’t yet turned into movies.

We spent about an hour at Meltdown, and then headed around the corner for a Coke at a nearby pizzeria. Guillermo told me he sometimes takes Ron Perlman there for a slice. I forgot to ask what Hellboy likes on his pizza.

Speaking of Hellboy, it recently became known that Hellboy 2 would be Guillermo’s next film. At the time of this interview it was all up in the air – I listed a bunch of possible projects to him and he told me he felt like they all had an equal chance of being the next one. Believe me, I wish I had gotten the scoop, but the guy just didn’t know. Sometimes things take forever to happen in Hollywood, and sometimes they happen over night.

When I finally got my voice recorder going we were already in the middle of our conversation, which had been happening since Meltdown. I would make up a fake question to stick at the top of this, but I respect you more than that.

Del Toro: However many movies I do, it’s all one movie. One movie that has a crazy ass action part now and then. It’s all one long movie – too long for some! You haven’t seen Pan yet, but there are thematic threads that connect Cronos, Hellboy and Pan. Then there are story and plot elements that join Devil’s Backbone and Pan. And strangely enough, Hellboy. I try to work carefully with the notebooks, saying that for the people who care, it’ll be there. For the people who give a fuck, it’ll be there.

Pan continues the fascist fairy tale concept. Del Toro: But it’s different because Devil’s Backbone dealt with proto-fascism, which means that it was more like a metaphor, a parable for the war, as opposed to being specific. Jacinto, the bad guy, was not a fascist because he did not have the elements – theoretical, social, political – to be a fascist. He was just a proto-fascist motherfucker. The bad guy in Pan’s Labyrinth is full-blown fascist. By choice.

Del Toro: But it’s different because Devil’s Backbone dealt with proto-fascism, which means that it was more like a metaphor, a parable for the war, as opposed to being specific. Jacinto, the bad guy, was not a fascist because he did not have the elements – theoretical, social, political – to be a fascist. He was just a proto-fascist motherfucker. The bad guy in Pan’s Labyrinth is full-blown fascist. By choice.

Pan’s Labyrinth is a different story – to me Devil’s Backbone is about how the only people who are complete are people who join. The rest of the characters stay individual and they are incomplete. When these kids join up, not by an idea or a political thing, but by mutual lackings, out of your miseries instead of out of your superiorities, it’s a beautiful thing. Pan’s is more about examining what choice means. Which is the same thing as in Hellboy for me… except with a Nazi clockwork motherfucker!

But it’s all about choice. How do you choose that which makes you who you are. That’s a key thing. I was raised Catholic, and when I was a practicing Catholic I used to wonder, what is the soul? And the essence of the soul is really… free will is an expression of the soul. And with free will you can find yourself and reinvent yourself or re-underline who you are every time you make a choice. Every time you say, ‘Fuck this guy’ or ‘Let me hear this guy.’ And you can make both choices; I don’t think there’s a right choice or a wrong choice, but they both make you into a different person.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but Pan was a real bitch to get made.

Del Toro: The thing is that Pan was the first movie that I wrote, produced and directed. Producing and directing is very tricky because basically the way you as a director disagree with you the guy who wrote the story and the way you the director disagree with you the editor is even more dramatic because you the producer disagree with you the director every day and you cannot live separate. You hate yourself every day. I really must say that I weighed in on the side of the director; therefore at the end of the movie I had essentially given back my entire salary because my choices as producer were not in favor of the numbers! But to me a good producer is not the guy who meets just to scale down the budget, but who makes the budget functional for the investors – even if he has to put in his own salary – but at the same time he never compromises the quality of the movie. If you take care of a schedule and a budget then you should run a travel agency, not a movie set. But if you do that while saying, ‘Is this movie going to look bigger and better than the budget?’ then it’s fine.

Is it easier for you now to find those investors? Do films like Blade II and Hellboy make it easier for you to find people willing to put money into your smaller projects?

Del Toro: To a point. It’s easier to find the money sometimes, but you always find yourself going back in time on how much… I remember one time on Mimic, which I did that movie for 30 million and I go back outside and I have to do Devil’s Backbone for 4. You find that if you were doing Devil’s Backbone in English they’d give you 30, but since you’re doing Devil’s Backbone in Spanish, they’ll give you 4. I don’t think there will ever be a filmmaker who will tell you, ‘I had enough money.’ If you need 1 million they’ll give you 700,000. If you need 20,000, they’ll give you 15,000, if you need 60 million, they’ll give you 30.

Why was it important for you to make Pan in Spanish? If you knew you could get more money if it was in English, why go for the lower budget language?

Del Toro: Because it’s not the same movie. There’s a really good movie with Haley Joel Osment and Willem Dafoe, set in Eastern Europe, called Edges of the Lord. It’s a really powerful movie about war and what it does to childhood, but it’s in English because it’s Haley Joel Osment and Willem Dafoe, and that for some reason immediately in my eyes makes it not the movie it needs to be. It should have been made with an Eastern European kid and an Eastern European actor. The fault is the thinking of the studio with packaging, but you cannot package yourself. Not for those movies. If you need 90 million dollars and you get Brad Pitt, God bless you. But if you’re making it under certain restrictions and you need to make it a little tighter but keep it real to its origin, better to tighten the belt a little bit. It’s not like that movie cost much more or less [with the actors], not that I can speak on that  case. I can say that 30 million for Devil’s Backbone or Pan’s Labyrinth in exchange for having Kieran Culkin as the Spanish orphan – it just doesn’t compensate. Now mind you, I think Kieran Culkin’s a fine actor –

case. I can say that 30 million for Devil’s Backbone or Pan’s Labyrinth in exchange for having Kieran Culkin as the Spanish orphan – it just doesn’t compensate. Now mind you, I think Kieran Culkin’s a fine actor –

But he’s just not a Spanish orphan.

Del Toro: He’s not a Spanish orphan. I think there’s only so much you can do. In Cronos, remember, we were promised – although it never fully materialized – they asked, ‘Do you want an American actor to get a little more money?’ And I said, ‘If we get an American actor I would rather do the villains as Americans.’ It can be organic to the story that the bad guys are American and they’re funny Americans in the way Sapito is funny in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Is it hard when you’re making films with budgets in the tens of millions then going back to making films whose budgets are so much tighter?

Del Toro: No, your brain works a certain way. You just assume all possibility of any luxury is gone. You think like that. It’s very simple – it’s the difference between taking out the garbage and kissing your family. It’s two different parts of your life. They’re all in a day’s work, but it’s two different hemispheres.

You keep getting attached to projects that don’t ever go anywhere. How frustrating is that to you?

Del Toro: Extremely frustrating because – I’ll give you an example: Aronofsky’s The Fountain, which I’m dying to see –

It’s unbelievable.

Del Toro: In 1997 I pitched to all the studios – no wait, 1993, with Cronos, I pitched to all the studios not that story but the concept of conquistadors and an alien spaceship. We all walk a tightrope – I think Stephen King said that – we all walk one single tightrope, creative people, and sooner or later if you don’t step on that certain point somebody else eventually will.

That’s what was frustrating in particular with Hellboy. Hellboy should have been made in 1997, when it was written and ready to go. Instead it gets made in 2004 when a lot of the novelty had worn off. So instead of being the first one, before X-Men and Spider-Man, you’re the seventh movie. You’re part of a universe that, when you conceived it, didn’t exist.

It is frustrating. It’s like with Mountains of Madness: I know that if I don’t do Mountains of Madness, somebody in two years will remake The Thing and I’ll be fucking biting the walls. But by virtue of one back and forth I really take my chips and cash them in to things that are not investment savvy. To take the good will from Blade II and Hellboy and cash it in on Pan’s Labyrinth is, artistically to me, very sane, but it doesn’t necessarily generate the clout to greenlight Mountains of Madness. Nothing is free – you know what you’re getting and what you’re losing, and I’m willing to trade a cold thing for a hot thing. But I carry them – Monte Cristo is with me for 13 years. Devil’s Backbone was with me for 16 years. Cronos was with me for 8 years. Hellboy was with me for 6. I wait and then they get made.

How does that decision-making process work? Is it that you decided you’ve made enough big films and now it’s time to make one for yourself?

Del Toro: It’s the same. I did Blade II hoping they would greenlight Hellboy. I knew that after Blade II I needed to do Hellboy right then and there or it would never happen. And the experience with Hellboy was very positive, creatively. It’s not like I wanted to go off and do something for myself. It felt very good naturally. You know how it feels? It feels exactly like if I don’t do this movie right now, no one else will. That was not the case with Blade II, but with all the others. I knew if I didn’t do Blade II, someone else would!

Blade II was going to happen. Del Toro: But even then it’s an interesting thing. I had come out of Mimic, and I said to the guys at New Line, if you really want me to do Blade II, you’ll wait for me to go and do my Spanish movie. Somebody suggested, ‘We’ll give you more money for the Spanish movie and it’ll come after Blade.’ They didn’t understand – I didn’t want it to come after, I wanted it to come before because I had said something to myself by doing Mimic and I wanted to say something else to myself by doing Devil’s Backbone now. If that means, I lose Blade II, I lose Blade II. So even then you can do those bets. And it paid off.

Del Toro: But even then it’s an interesting thing. I had come out of Mimic, and I said to the guys at New Line, if you really want me to do Blade II, you’ll wait for me to go and do my Spanish movie. Somebody suggested, ‘We’ll give you more money for the Spanish movie and it’ll come after Blade.’ They didn’t understand – I didn’t want it to come after, I wanted it to come before because I had said something to myself by doing Mimic and I wanted to say something else to myself by doing Devil’s Backbone now. If that means, I lose Blade II, I lose Blade II. So even then you can do those bets. And it paid off.

Was Mimic your worst experience?

Del Toro: Filmically? It was, because I didn’t know a lot of things that I know now instinctively and empirically. I came from a country where you make movies in a collective way, where your friends help you. You have a friend that has a camera, you have a friend that has two lenses, so you love and listen to all of them. I went from that to an industrial environment. You learn a lot.

Will there ever be the Guillermo Del Toro cut of Mimic?

Del Toro: I hope. I went to Disney and I begged them to put it out on DVD and they would not do it right now. Hopefully down the road.

Did they give a reason?

Del Toro: I think the whole market is very scared of how the drop of DVD has been affected by director’s cuts of everything under the sun. Director’s cut of Spider Baby and you have three cuts of whatever – I think they are affected by that. And I can understand that; I don’t mind. But I think it will be the only director’s cut that is shorter than the theatrical version!

What’s the current status on Hellboy 2?

Del Toro: I don’t know. Literally today is different than yesterday. It’s very dramatic because it’s a sequel, and it’s not usual that a sequel is being shopped around. It sounds like a great opportunity but the truth is that the entire business is contracting, and Hellboy is in that mid-range of a price that is a risk. Look, I make peace with these things. I try to make them happen – really, really try – but there comes a point when you cannot castigate yourself. You have to ask, what can I give? With Hellboy, half my salary was put into the movie. I never got it back. Fine by me. But you cannot do any better. If I had 80 million I would put that in. But I don’t have 80 million.

How important is it these days that, to be a good director, you have to be business savvy?

Del Toro: You have to be very good at structuring or you have to be very good at letting go. You have to be savvy about making other people some money but you should not be in it to make as much for yourself as you can. Then you’re turning into something else. You can let your agents do that if it’s an industrial movie, but at the end of the day you have to say, ‘If that’s the way to make the movie, let’s make the movie.’

Where did Pan come from?

Del Toro: It’s a long story. I’ve always collected fairy tales. I have a very hefty fairy tale collection in my library, and I was always interested in the mechanisms of fairy tales – which are different from a lot of other literature. It’s not the Joseph Campbell method, which is to me a very old structure and kind of Anglo-Saxon and a little creaky. I like that the fairy tales have a rationale that is self-explanatory. Things are what they are because they are. The  quests are very particular. I found out doing Pan that I am actually sort of a closet fantasist. I’ve always thought of myself as a horror guy, but I have found out more and more – there’s a strange thing, the more I do horror movies I am not interested in the scares. I’m interested in the creepiness, I’m interested in the under your skin images, but I’m not interested in the scares. I’m not interested in the movie traps; I’m interested in the poetics.

quests are very particular. I found out doing Pan that I am actually sort of a closet fantasist. I’ve always thought of myself as a horror guy, but I have found out more and more – there’s a strange thing, the more I do horror movies I am not interested in the scares. I’m interested in the creepiness, I’m interested in the under your skin images, but I’m not interested in the scares. I’m not interested in the movie traps; I’m interested in the poetics.

That’s Lovecraft. Lovecraft is considered horror, but it’s really fantasy stuff. It’s not about immediate scares but about imagery that stays with you.

Del Toro: It is. I think the French, with Rimbaud and Baudelaire there was this idea of graveyard poetry. I subscribe to that idea, which is that horror not only scares – it’s like comedy. I can laugh my ass off watching Dumb & Dumber, which I do, or the fart contest in Family Guy; I’m a simple guy with comedy. But then again I consider high comedy some very bittersweet moments in Chaplin or Woody Allen that I don’t even smile at. They hit something different, but it’s humor. I think horror, most of the time, is thought of as the fart contest equivalent. Do my movies kick major ass with gore? Eh, some days. On a good day Blade II is pretty fucking nasty. But the others, they work a lot in fantasy terms.

Before Pan’s Labyrinth I got offered the first Narnia. The head of Walden called me, he came to the editing room of Blade and said they wanted to do Narnia. Growing up I really loved those books. Back then I was Catholic, and I loved those books. But I said that rather than doing Harry Potter or Narnia I’m going to do my idea of what these stories mean in juxtaposition with the real world. As a guy that dreams a lot what I find is that the world tries to destroy you when you’re dreaming. It’s not this idealistic jerk-off fucking ‘Oh fantasy’s so precious!’ No, the best expression of this to me is Brazil by Terry Gilliam. It’s the ultimate movie about the clash of reality, the most obscenely every day reality, which is bureaucracy, and it clashes with fantasy.

I was interested in seeing fascism, which is the absolute lack of imagination, the absolute lack of choice and the most masculine expression of power, juxtaposed with the most feminine, most beautiful expression of power, which is imagination. By this I don’t mean genitally – I mean existentially male or existentially female, which is different from how you’re built! One is an inclusive power and one is an exclusive power. Male power is exclusive. Female power is inclusive; it’s about the ability to nurture, embrace and grow. The other is about the urge to… invade, for a lack of a better term. Let’s conquer Poland, shall we?

When you talk about fairy tales I think people in the United States will get a very different impression than what they’ll really see in Pan.

Del Toro: I think if people are expecting to see David Bowie chanting and dancing they’re going to shit in their pants. If they’re expecting the fucking Goblin King talking to Jennifer Connelly, they’re going to shit in their pants.

There’s a whole – I won’t even say psychosexual, because it’s beyond that – there’s a whole Jungian component to fairy tales that is extremely interesting and it only comes out most of the time unintentionally. In movies it has been explored in a psychosexual way by Neil Jordan  in A Company of Wolves, but it’s not been explored beyond that. In reading fairy tales I found they broke into two big categories. You can divide them clearly and say there’s the story about returning to your mother’s womb, which is the child reaching heaven, or there’s the story of coming out of your mother’s womb and battling the dragon. And that deals with temptation and violence and all that, and I thought it would be interesting to do it from that point of view, a point of view that’s not psychosexual but more existential, more Jungian.

in A Company of Wolves, but it’s not been explored beyond that. In reading fairy tales I found they broke into two big categories. You can divide them clearly and say there’s the story about returning to your mother’s womb, which is the child reaching heaven, or there’s the story of coming out of your mother’s womb and battling the dragon. And that deals with temptation and violence and all that, and I thought it would be interesting to do it from that point of view, a point of view that’s not psychosexual but more existential, more Jungian.

While there’s this subtext there are also really kick ass monsters.

Del Toro: Yes. There has to be. There has to be. To me, for example Hellboy, hopefully people who saw Hellboy the first time and kind of like it can give it a second chance, because I’m almost sure it’s the kind of movie that grows on you. I tried to make the trappings of the genre work and then I tried very hard to make them work on another level. Like Devil’s Backbone is a gothic ghost story, but at the same time it’s going against the grain – what normally would be a damp English castle is now a dry orphanage in the desert. It really goes against the grain, and the same goes for Hellboy. The only full-blown frontal nudity, I am what I am movie I have ever done is Blade II. It’s all there, baby, take it for what it is.

It’s all text.

Del Toro: Sometimes a cigar is a cigar… and a Blade is a Blade!

But all the others need to function in two ways – a fairy tale needs cool monsters. A fairy tale needs creatures. So a fairy tale has those but I think that people that are looking for a hardcore fairy tale will be disappointed. They’ll walk out saying, ‘It’s not for me.’ You have to be very open. Cronos worked on a level that was very different from Devil’s Backbone. It’s a level where you mix genres, and if you’re not willing to do that, you’ll be disappointed. If you come to Cronos and you expect to see Vampire Lestat, with glitter rock and vampy sets, you’re going to say, ‘What a piece of shit this movie is.’ But if you’re open to riff, it’s a great riff. If you go to Devil’s Backbone expecting to see The Others, you’ll be disappointed, but if you want to riff… Same is true for Pan’s Labyrinth.

When he made What Lies Beneath, Zemeckis put the whole movie in the trailer because he said people like McDonalds – they like knowing what they’re going to get. People don’t know what they’re getting with your films.

Del Toro: Sadly, no, I am not like McDonalds. I am an extremely acquired taste. I’m the 3000-year-old egg, man. Not everybody wants to eat it, but it’s on the menu.

And the people who do eat it love it.

Del Toro: Fuck yeah. I’m snails; I’m frog’s legs. I’m the weird fucking dish. But if you like it you come back and you’re very happy. A lot of time I meet people who tell me they loved Blade II and hated Devil’s Backbone.

How can that be? Does that drive you nuts?

Del Toro: No. Popeye and Christ say the same thing: ‘I yam what I am.’ You’ve got to listen to a guy with one eye and big forearms. He’s got some wisdom.

Let’s go back to the monsters. You showed me your diaries and I see these amazing drawings and designs – what are you drawing from? What are your inspirations?

Del Toro: Pan’s Labyrinth comes very specifically from Arthur Rackham. When I was doing the diaries during Devil’s Backbone I was drawing images for Pan’s. I’ve been working on images for Pan’s since 1993.

Before doing Hellboy I said, ‘You cannot do the movie if you cannot draw the character.’ So I did this one [shows great Hellboy color image], and it’s not a great Hellboy – I showed it Mignola and he winced – but I needed to know how to do the Rackham trees. And then the dissection of a gnome. Then eventually I think there was a pretty good Corben Hellboy.

So I think the way to capture these creatures is to say these are the sources and let me figure out what makes them work. The color palette – I learned a lot about the color palette by doing this. Then you learn the shape palette. And you internalize it by drawing. It’s like eating – I’m a big fucking eater, and when I go to the restaurant I want to know how they  made it. But first I taste it and I say, ‘Ah, this has a little bit of cumin and this has a little bit of mint,’ and then you ask. And you’re wrong – it has pineapple! I think if you’re a director, in order to create your pictures on your sets you have to be able to articulate them in form. I have to be able to draw the throne room in Pan’s Labyrinth or the ghost in Devil’s Backbone. When we were doing the ghost in Devil’s Backbone I kept saying to the guy – they wanted to do a rotting corpse, and I said, ‘No rotting corpse. It has to be broken like porcelain.’ It has to be real. Who’s to say if a ghost ever rots, but I believe it gives you the idea of a fragile doll and it’s more icky and disturbing that way. And beautiful.

made it. But first I taste it and I say, ‘Ah, this has a little bit of cumin and this has a little bit of mint,’ and then you ask. And you’re wrong – it has pineapple! I think if you’re a director, in order to create your pictures on your sets you have to be able to articulate them in form. I have to be able to draw the throne room in Pan’s Labyrinth or the ghost in Devil’s Backbone. When we were doing the ghost in Devil’s Backbone I kept saying to the guy – they wanted to do a rotting corpse, and I said, ‘No rotting corpse. It has to be broken like porcelain.’ It has to be real. Who’s to say if a ghost ever rots, but I believe it gives you the idea of a fragile doll and it’s more icky and disturbing that way. And beautiful.

I think you go by this process and you make it your own by drawing it.

Does the visual stuff come first? Does the story stuff come first?

Del Toro: They come at the same time. With Pan’s Labyrinth we had twelve weeks to design the movie; three months. So every time I would draw a piece of shit idea for the set the set would come out to be a beautifully expressed version by another artist of that piece of shit idea.

I love what Cuaron said on Children of Men at the Comic Con panel. He said, ‘I like working in English because English is not my first language, so most of the time people do what they think I said, which is better than what I actually said!’ I am like that with the drawings – people do what they think I drew, which is much better than what I actually drew!

People talk about eye candy; I try to do eye protein. I really think that no matter how smart, great and beautifully crafted a piece of dialogue is, the roots of that piece is in theater, it’s dramaturgy. The root of cinema is unique to audio/visual. To me 90% of what makes an image memorable is not the literary content, but the meta-literary content – it has a suprameaning, and it’s all in the image and the sound. There are movies like Zombi or The Beyond by Lucio Fulci where, all of a sudden, in a movie that Robert McKee would fully disown, there are two minutes of absolutely insane poetry. Dario Argento’s Inferno, with the girl diving into the inundated basement, which I quote in Hellboy with Abe Sapien, is such… it’s as poetic as Cocteau. Will the WGA ever award Argento a prize for that screenplay? Fuck no. But why does that image live in me or you or a hundred more people in the theater? Because images and sounds speak to the deepest cerebellum part of our brain. I think you have to craft the sound and the image with as much care as you can. Those are choices that come from your gut – you can qualify them but images you can never grasp and you can never capture them.

You can say, ‘What a piece of shit movie Blade II is!,’ and maybe on a good day you’ll flip the channels and remember the pussy-mouthed motherfuckers and think, ‘Those are cool creatures.’ That’s fine by me. I’m at peace with that.

I was going to say that when you create the pussy-mouthed vampires or the ghost standing in the hallway in Devil’s Backbone, these images that stick with me to this day, are you surprised that these images come out so powerfully, or do you feel that from the beginning?

Del Toro: For example if we go back to the notebooks, with Devil’s Backbone, you can see from the earliest moment there’s a shape that will be in the movie at the end of the day. It’s not accidental. There’s one shape that will guide the movie through, or the texture. For  example, when we painted that corridor and I knew we wouldn’t have the money for the arch, I said, what can I change that will make the scene more interesting? I knew the background of that wall needed a particular texture. Maybe if you watch the movie again, you’ll see how rich the texture is. Why? Because it’s the only way to see the water in the atmosphere moving around the ghost. So you have to calculate them – the only thing is that you have to be very fluid in that language, because during the day the difference between a 28 and a 50… you have to choose the right kind of lens. And the difference of the camera being a foot and a half or three feet from the ground, and moving or not moving, these are decisions that can only come out when your craftsmanship allows you to articulate that language.

example, when we painted that corridor and I knew we wouldn’t have the money for the arch, I said, what can I change that will make the scene more interesting? I knew the background of that wall needed a particular texture. Maybe if you watch the movie again, you’ll see how rich the texture is. Why? Because it’s the only way to see the water in the atmosphere moving around the ghost. So you have to calculate them – the only thing is that you have to be very fluid in that language, because during the day the difference between a 28 and a 50… you have to choose the right kind of lens. And the difference of the camera being a foot and a half or three feet from the ground, and moving or not moving, these are decisions that can only come out when your craftsmanship allows you to articulate that language.

I would really love to think that in a great percentage of movies those images are not found, but that happens. You have to be humble and welcome chance. You have to say that this is better than what I thought.

What level do you think you are as a craftsman? People who have seen Pan keep coming back to me and using words like ‘masterpiece.’ Do you feel like you’re on the top of your game?

Del Toro: Pan’s is a film where I think like a dog my balls dropped. ‘Hey, there they are! Finally!’ I’m walking and there’s a certain sway that’s different. But I could not have done Pan without having done all the other stuff.

If you’re talking exclusively about craftsmanship – there’s a lot of bullshitting in our work, where the director most of the time is a fucking poseur who is full of doubt and scared shitless. And you should be scared shitless – if you don’t have any doubts the movie will be stillborn. You have to have that fear there. You calculate everything and the day throws you something else.

In Pan’s Labyrinth there’s a war sequence, and before shooting the war sequence the fire marshal came in and said, ‘You cannot use a single blank or any squibs. You cannot use any fire.’ And it’s a night sequence with fire and explosions! You think, ‘Ugh, what am I going to do,’ and then I thought, I’m going to go theatrical. I’m going to do it like a stage play. I’m going to use light and steam, and cork exploding in water to be the abstract expression of my explosions. And no one has commented on it in all the screenings. It’s about craftsmanship.

And you have to be humble – it’s not about vision and I’m this ethereal, delicate creature. No, no, no. There’s as much craftsmanship in it as the guy who makes your fucking chair, a guy who makes a section of the floor. There’s craftsmanship. I am just a fucking craftsman who deals with a different set of tools. That’s why I love Hellboy. Hellboy is a fucking plumber. He comes in and says, ‘Where’s the leak? Oh fuck.’

Artists, in their origins, get to a point where craft serves a purpose, and then after certain point where the artist becomes this digressive mind, the anarchic mind, they acquire the cool quote unquote status. But up to a point it’s like, ‘He died of hunger? Fuck him. He committed suicide? Sure, he’s an artist.’ They weren’t the delicate outcasts: ‘Leonardo won’t finish your painting, sir.’ ‘Fuck him! Sue him! I want that painting of my wife for my fucking living room!’ But now we have this delicate, I’m an artist, my vision…

If I’m proudest of anything on Pan it’s the craftsmanship. You may like it, you may not, but even at my worst as a craftsman, I do my work. The chair has four legs. You may not like it as much as another chair, but it’s a chair. And with that comes the possibility of articulating your ideas slightly better. Craftsmanship is your language; the ideas are the poetics. If I’m better at syntax, the better my ideas will come to be heard. And I think Pan has better syntax than the ones before.

Before you talked about Cuaron. I know you are really great about finding people and working with people and supporting them – you’ve done it with Cuaron, you’ve done it with our own Nick Nunziata on Meg. Why is that important to you?

Del Toro: The industry in Mexico was very tough. Growing up you needed to work your ass off going up the ranks to make movies. I worked for fifteen years before Cronos – I did  assistant directing, I was a boom guy, I did storyboarding, I did PA, I did all that shit. At the end of the cycle, around 1990, people started giving me breaks. I really loved it. In 1986, 1987, Dick Smith gave me the big break; he said, ‘I like your drawings, you’re an OK illustrator. You’re a mediocre sculptor – he was very frank! – there are people much more talented than you for the make-up effects, but you need it the most to do the movie you want to do.’ I said, ‘If you don’t give me the break of learning the make-up craft, I’ll never make Cronos,’ and he gave me the break. He was an Oscar winner, he didn’t need to give me a break.

assistant directing, I was a boom guy, I did storyboarding, I did PA, I did all that shit. At the end of the cycle, around 1990, people started giving me breaks. I really loved it. In 1986, 1987, Dick Smith gave me the big break; he said, ‘I like your drawings, you’re an OK illustrator. You’re a mediocre sculptor – he was very frank! – there are people much more talented than you for the make-up effects, but you need it the most to do the movie you want to do.’ I said, ‘If you don’t give me the break of learning the make-up craft, I’ll never make Cronos,’ and he gave me the break. He was an Oscar winner, he didn’t need to give me a break.

I learned that whatever you have, pass it on a little bit. The guy that did the storyboards on Hellboy and Monster House and the Monster House comic? He was in a Virgin Megastore in the DVD section when I met him. He said to me, ‘Will you give me a break?’ Two of the guys on Hellboy were guys at conventions who had good portfolios but nobody was going to give them a break, so I said, ‘Come for a week, you’ll get what you get for a week, but your curriculum will say “He did things for Hellboy.”’ Does that imply a huge effort? Sometimes it does, and I’ve had bad experiences – guys who take that opportunity and instead of being cool about it, they’re assholes. But you can’t fault them. I think it’s just about what can I do for someone that someone did for me? It’s as simple as that.

Cronos? Based on my short films, it should never have been made! They’re the worst short films ever made. I see the kids DVDs now – they’re savvy. I go, ‘Oh my God, thank God I’m 41 and working! If I was 18 I would be out of a job!’

Do you go back and look at your older films?

Del Toro: Accidentally sometimes. Two weeks ago I was watching cable with my daughter and we passed Hellboy and she said, ‘Let me watch it!’ We watched all the way to the end. But only accidentally, I never go and have a little retrospective.

Do you always feel good about a film when you finish it? I guess except for Mimic…

Del Toro: But I love an entire hour of Mimic. Love it! But there’s another half hour I don’t like!

But the rest of your films, do you love them all?

Del Toro: Not all. Not completely. I love Pan’s Labyrinth. I love Devil’s Backbone. I love Hellboy. Those are the three top. And funny enough, I love Blade. And if people are shocked, for example, by learning that I love Blade more than I love Cronos, so be it. I am not trying to be in agreement with anyone’s opinion, I’m not saying it’s a better film- I just think Blade had a very healthy effect on my life. Look, Cronos– it won the Critics Week in Cannes, it won 9 Academy Awards in Mexico, but I suffered so much to do it that I cannot get past all the things I did wrong. All the wrong decsisions I made as a first time filmmaker. Frankly, the healthiest thing, the most humblingthing that could have happened to me was to do Mimic. If I had been in a corner looking at my belly for three years until I made another "masterpiece"…

I don’t know why Cronos worked, as much as I don’t know why other movies haven’t worked. But the fact is that [after it] I went and did the most humbling thing I could do, which is go through hell on a giant cockroach movie! There’s nothing more humbling than that. I knew  when I was going through hell at the end of the day, after I suffered the torments of hell, it’s still going to be a giant cockroach movie. But I had to deliver it. There’s a very healthy effect that has on you.

when I was going through hell at the end of the day, after I suffered the torments of hell, it’s still going to be a giant cockroach movie. But I had to deliver it. There’s a very healthy effect that has on you.

Blade, if I had started to wonder if my ‘auteur’ signature would be… Blade II, motherfucker. Get in, have fun. I had the most fun I ever had on Blade II. After pretending I was either Mozart or fucking Kenny G depending on whoever saw the other movies, I had the chance to be Metallica or Massive Attack for a few minutes! It was something I liked, and I didn’t have to pretend I didn’t like it.

I love Blade II. Any movie that ends with a wrestling match…

Del Toro: Yeah! But a funny thing that people say is, ‘Why do you have the wrestling match?’ It was an organic process – I came up with part of it, and Wesley came up with the suplex. Wesley said, ‘I want to do a suplex,’ and I said, ‘Let’s do it on the glass floor!’ What’s a better place to do a suplex than a glass floor?

And you know what? Movies are like a religion or a blind date – you connect with some people and you don’t connect with others. You can’t convince a Muslim or a Jewish man or a Catholic man that the other religion is the one. You like what you like.

So how do you judge the success of a film? Is it critics? Is it box office? Is it the reaction of fans?

Del Toro: It is how close it is to the thing you wanted to do. That’s success. It’s not how much it makes or how many people tell you that you’re bitching. It’s about does the kid resemble what you thought you wanted in a son or a daughter? Are you fulfilled? My daughters, every time they win a prize in a dancing contest, I love it. There’s a fulfillment in that. It’s about that, it’s about how close you are to that.

Mimic is not hurtful because of the bad anecdotes but because the movie I wanted to do was so much cooler than the one I ended up making. I don’t complain. There was this book, Down and Dirty Pictures –

By Peter Biskind.

Del Toro: I disagree with the way that it’s presented in the book very much, but I think every time you glorify your suffering as a filmmaker, there’s something slightly arrogant about it. I worked in the real world; I did five years in real estate selling apartments, going to the bank and waking up at 6 to check the delivery of cement. You know what, how can you complain? How can you say, ‘Boo hoo, they mistreated me’? Fuck you! Get a real job, then come back and kiss the ground they walk on. Fight for it, but just don’t complain. Work makes it alright.

What are you watching these days? What are you reading these days?

Del Toro: I’m reading mostly Tarzan novels right now. I’m reading the entire canon of Tarzan, in order.

What is it about Tarzan that made you pick up the books?

Del Toro: He’s one of those characters that you remember one way as a kid, and you say, ‘Was he that cool?’ I had read 15 of the novels – I was lacking a good chunk – so I said, why don’t I go complete the collection, buy them all, and read them in order?

Raymond Chandler, when I started reading him, I read him in order, and there’s something to  it. When you read Dickens all at once, or Chandler all at once or Burroughs all at once, you see where they repeat themselves. With Raymond Chandler, John Dalmas gets repeated later in later detectives. And you even see exact phrases.

it. When you read Dickens all at once, or Chandler all at once or Burroughs all at once, you see where they repeat themselves. With Raymond Chandler, John Dalmas gets repeated later in later detectives. And you even see exact phrases.

Because back then they thought nobody was paying attention.

Del Toro: When they came out, people threw them in the garbage when they were done with them.

What’s interesting about Tarzan is that we have this one ape man image of him, but the Burroughs books get very weird.

Del Toro: Extremely weird. They’re much nastier than the Tarzan in the movies, and much more complex than the Tarzan in the movies. They have more monsters and adventures and lost cities. They have a lot more going in the fantasy aspects.

I’m reading that. I’m watching – by being a father, I watched Mulan for the 20th time. Or The Lion King 1 ½. That’s always in the roster. But thankfully, mercifully, my daughters have also been brought up on Miyazaki and Takahata. Last week we watched a movie called Junkers Come Here, an anime that was recommended by a fan in one of the forums, and we went and got it and loved it.

How much attention do you pay to the feedback on the internet? Some directors don’t go there at all and some take it too much to heart.

Del Toro: I do it because I love how democratically obscene it is. You can read a TalkBack about Spielberg or Peter Jackson and half of them are going to take a shit on their mother’s grave. It doesn’t matter who you are. And you know what? If you take it as that’s the gospel, you’ll be affected. But if you take it as a skin-thickening tool, it’s great.

Is it real, everything that’s online? No, everybody has a persona. It’s like wrestling – you have the bad wrestler and the good wrestler, but nevertheless they’re telling you something you’ll never hear in this town. In this town when you meet with the exact executive who is going to fuck you up the ass a year later, the first meeting you have is, ‘I’m a huge fan, I want to help you get your vision to the screen!’ A year later it’s like, ‘What is that in my back? Oh, it’s you! My biggest supporter!’

It’s great not to be in a fluff cloud. I don’t go every day, but I go to dangerous places now and then. And if I cannot hear that… sometimes when it is really absolutely unfair, there’s a little sling that goes through, but it’s good. You’ve got to listen. It’s not the gospel, but it’s another opinion against what you get here.

So Pan is out in December. Is there a release plan for that yet?

Del Toro: The idea is that they’re going to release it wider than the regular arthouse movie, but I don’t dare so a number. Look, as long as it’s somewhere in each state, I’ll be happy. Devil’s Backbone got a very small release and a lot of people discovered it on DVD. You never know with a movie – it’s final resting place is never sure. When I’m on the set and we’re fighting to get a shot, I tell the guys, ‘Remember, it’ll live forever in the video shop.’

What’s your take on the more alternative release strategies? A lot of CHUD readers are excited about Pan, but they don’t live in the towns where the movie will play, and they’ll have to wait a long time to get it on DVD…

Del Toro: The reality is that I remember when I lived in Mexico when I was a kid, we would get the American movies a year after, or a year and a half after. I had to learn to read English so I could buy Famous Monsters and Mad Magazine to see what the movies were that were going to be a year away. Because Mad would satirize the movies and Famous Monster would announce them. So I learned English with those magazines.

You know, I think that we live in a moment in time that is very curious in that instant gratification has taken the luster out of any form of art, music, painting. Everything has to be now, here, accessible. Ultimately what does that mean? Money? Faster, bigger, and then there is repeat business. But I don’t think it’s doing the form a lot of good. You can see it at Comic Con or E3 or any of these massive gathering

now, here, accessible. Ultimately what does that mean? Money? Faster, bigger, and then there is repeat business. But I don’t think it’s doing the form a lot of good. You can see it at Comic Con or E3 or any of these massive gathering