James Toback says he took more hits of acid than anyone else in history. James Toback bet a million dollars on a baseball game. James Toback was going to hire a hit man to kill Barry Levinson until he and Levinson became friends. James Toback lived in Jim Brown’s house and took part in star-studded orgies. James Toback is a lothario, just like Robert Downey Jr’s character in The Pick-Up Artist.

James Toback says he took more hits of acid than anyone else in history. James Toback bet a million dollars on a baseball game. James Toback was going to hire a hit man to kill Barry Levinson until he and Levinson became friends. James Toback lived in Jim Brown’s house and took part in star-studded orgies. James Toback is a lothario, just like Robert Downey Jr’s character in The Pick-Up Artist.

That’s the icing on the Toback cake – the really important part is that James Toback is one of the most important indie filmmakers of our time, a guy who makes movies on impossibly low budgets about incredibly taboo and provocative topics, and they’re movies that he wants to make. Toback has a vision, and whether you like it or not, his movies carry that vision.

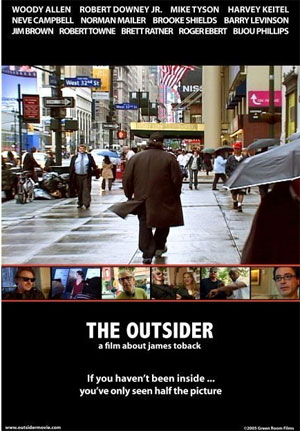

Nick Jarecki’s documentary The Outsider is partially a behind the scenes look at the insane 12 day shoot of Toback’s last film, When Will I Be Loved, and is partially an examination of the man himself and his storied – and self-mythologized – life. Jarecki gets people like Robert Downey Jr, Mike Tyson and Woody Allen to look back at Toback’s career and try to make a little sense out of this larger than life man.

I did a phoner with Toback yesterday, and halfway through the call I had a perfect Toback moment – he stopped to buy Lotto tickets. His first script, The Gambler, is a very autobiographical story about a guy with a serious and compulsive gambling problem; in The Outsider Toback says that he could quit smoking and drinking but has never been able to quit gambling. The rest of the interview isn’t so bad, either – it’s Toback being smart, funny and wildly honest.

The Outsider opens in New York City today and I can’t recommend it enough. It’s a great film for anyone interested in learning more about one of the more outrageous characters of cinema, and you don’t need to know very much – or really even anything – about Toback to enjoy the hell out of this one.

Q: What’s the relationship between you and Nick Jarecki?

Toback: It started out that I only knew him through a book that he had done called Breaking In, which documented 20 filmmakers and how they made their first movie. Then he talked to me about coming on to the set and making a documentary about the making of When Will I Be Loved. I thought if he has any cinematic talent – I knew he was a bright guy, and he seemed like a nice guy – if he has any cinematic talent, it’ll be good. But you don’t really know about that, because there’s a special gene. He turned out to have a great deal of cinematic talent, and as I saw some of the footage that he assembled, I though, ‘Well, I’m glad I said yes.’ He proposed making it into something more elaborate, which I also found to be an intriguing idea, so I said yes to that. It paid off. I introduced him to people who ended up being integral to the film. We enjoyed each other’s company, it was a fun thing to do.

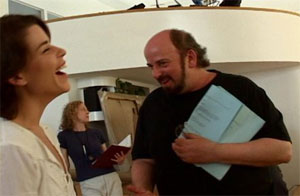

Q: Was there ever a point you regretted having that camera on set all the time? Toback: No because I forgot it was there, as you can tell from my total lack of vanity in the way I was shot. If I had been vaguely aware he was there I would have made some effort to look anything but my absolute worst in every shot.

Toback: No because I forgot it was there, as you can tell from my total lack of vanity in the way I was shot. If I had been vaguely aware he was there I would have made some effort to look anything but my absolute worst in every shot.

Q: Taking on When Will I Be Loved seems like a crazy thing to do, making a movie in 12 days. How is that appealing to you? Is it appealing to you as just a filmmaker or is it appealing to the gambler in you as well.

Toback: I certainly think a personality that enjoys risks would want to get into that, would allow oneself to get into it. There are all sorts of pitfalls, and I think I’m probably intrigued at the idea of avoiding them.

But you know there isn’t any company with 60 million dollars coming around and offering it to me, so you work on a practical level with what you have to work with.

Q: Is it that there aren’t companies coming to you, or is it that you don’t want to go to them? You’re certainly well known and you make interesting films, and there are people throwing money at filmmakers who aren’t making movies half as interesting as yours.

Toback: Do you have any idea how fucking stupid these people are?

Q: How fucking stupid are these people?

Toback: Imagine the dumbest people you can imagine in jobs like that. Obviously they can cross the street, but given who they are and what they do – and I’m not saying there aren’t exceptions, there are a few – but take the lowest common denominator of what you would assume it would take to hold a job like that and then drop down four more floors. That’s what you have.

Q: So is part of it that you’re not willing to go and deal with these dummies?

Toback: I can’t engage in conversations that are patently idiotic and have a pretense and go along with them. I am not, nor am I capable of being, a blatant hypocrite when I am interested in something. If I’m not interested in something I may be able to sing along with Mitch, but if it actually means something to me, as movies do, I just can’t pretend… Just look at the movies that are coming out of that factory. I’m making movies that come out of my own obsessions and interests, and that’s what I do. First of all that kind of movie is only being made fitfully and intermittently. Very few of these movies get made without a big star. If I came to them with something that had six sequels built in, an apparent franchise film, it would be easy.

You have to deal with whom you like. John Calley is a great guy. He’s not running Sony anymore, but John Calley is a really smart, interesting guy who you can be straight with. That’s a dying breed.

What do you want to accomplish in a film career? Why are you doing it? Why is it important to do as opposed to… something else? What is it that makes it worthwhile. I think if you have an answer to that question, you have to stick with it. I’ve been making movies for 32 years, and you can’t do that if you’re not coming from a place of serious obsessive commitment. It has to come from something fundamental from you that you’re getting out and creating something through it. You can’t do it otherwise – you’re not going to last. I’ve been incredibly lucky, and I would stress more than anything that I’ve been incredibly lucky to find stuff I want to do and be able to do it. I haven’t had a pile of money to do it with, and I’ve had dreadful distribution most of the time, but it’s a small price to pay. But I prefer that to having to do a bunch of movies I didn’t want to do or having to compromise on the movies I did and made a lot of money and had a lot of theaters.

Actually, anyone investing in my movies would have made a lot of money, which is true of maybe five percent of people directing.

Q: Because the budgets are so low.

Toback: Right. If you had invested in me, you would be way ahead of the game. If you had invested in a lot of famous and well-established directors, you would be way behind the game. I haven’t counted, but I would wager that if you had just invested in Marty Scorsese’s movies, you would be bankrupt.

invested in a lot of famous and well-established directors, you would be way behind the game. I haven’t counted, but I would wager that if you had just invested in Marty Scorsese’s movies, you would be bankrupt.

Q: I find it really interesting that you’re someone who became well known for your scripts, you have such great dialogue, yet in your latest films you seem to be moving more into improvisational stuff. Why is that?

Toback: It’s case by case. If I’m making Black and White, I’m not going to write Wu Tang Clan’s dialogue for them. I’m not going to write Mike Tyson’s dialogue for him. It’s just never going to come out as well as if I make my intentions clear and let them go with it.

That’s the obvious place, but there are less obvious situations like the scenes with Neve and me, and Mike Tyson, Neve and the girl in the loft, Lori Singer – those scenes seem to me to call for… listen, you can only do that with actors who are very articulate and smart, which many of them aren’t. A lot of good actors have become actors because they’re completely inarticulate and they like the idea of having interesting dialogue written for them.

For the most part, for whatever reason, I’ve gravitated to very articulate and smart actors. But I have no rule, and I’ve somewhat unjustly gotten the reputation of someone who wants to do that. Black and White is half that, Two Girls and Guy is incredibly tightly scripted – only one scene is improvised, and that’s the one in the hot tub. When Will I Be Loved is half very tightly scripted; every word of the dialogue with Neve and Dominic Chianese was written. I mix them.

The thing is to not be dogmatic, to not think I’ve found the way and think that’s the way to do everything. That’s why it’s so dumb to say, ‘This is the way to treat actors, to talk to actors.’ Actors are people, and you have to say these are individuals and get to know them and see whom I work well with. I think I am as good a director as has every existed for the people I’ve directed, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t a lot of other actors I haven’t directed who I haven’t directed partly because I certainly know that I would not be the perfect director for them.

Q: Do you ever make the mistake of ending up with actors who you’re not perfect for?

Toback: That’s never happened to me except for Ray Sharkey [in Love and Money]. I had David Picker, the lout who was running Lorimar at the time, said you can have one of three actors or you can’t make the movie, and I was so desperate to make the movie that I went along with it. None of the three actors was really it; I wanted to use Harvey Keitel and he wouldn’t let me use him. I ended up with Ray Sharkey, and it’s not that we didn’t get along, it’s just that we weren’t a good match. And he was wrong for the part, and it shows.

Q: In The Outsider we see your friendship with Brett Ratner, who is almost the Anti-Toback when it comes to the kinds of movies he makes. Do you give him advice, try to get him to make something more personal?

Q: In The Outsider we see your friendship with Brett Ratner, who is almost the Anti-Toback when it comes to the kinds of movies he makes. Do you give him advice, try to get him to make something more personal?

Toback: He’s been a really devoted admirer of mine, and I like him. He’s fun, he’s smart, he’s a very loyal guy, and he knows what he’s doing. He’s a shrewd, smart, talented operator. He knows where he wants to go, he knows what he wants to do. He deals with people with great confidence, both actors and that whole executive world in Hollywood, which he handles with great skill. If he asks me advice, which he sometimes does, I give it to him. But he’s doing alright on his own.

Q: Did The Beat That My Heart Skipped turn up the heat on you last year?

Toback: Not really. No.

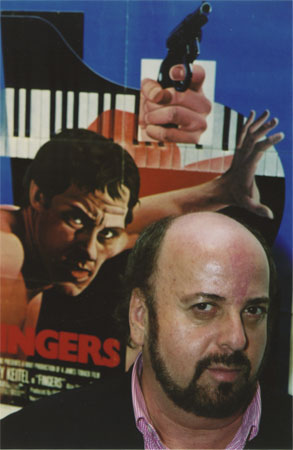

What’s interesting about that is that when Fingers came out there was a French critic named Michel Ciment, he’s an editor for Positif, and he referred to the people who loved Fingers as ‘We happy few.’ I refer to them as Fingers Fanatics, because over the years – and Harvey Keitel gets this too – we get stopped in the street. Poor Harvey has people stopping and yelling ‘Fingers!’ Harmony Korine stopped and yelled ‘Fingers!’ at the Telluride Film Festival.

The majority of people at the time were vicious to the movie. Not negative – vicious. Vincent Canby and Janet Maslin gangbanged the fucking movie. They couldn’t foam at the mouth enough to try to get it out of distribution as quickly as possible, as if it were a personal affront to their vast artistic integrity. I find it amusing that it’s not a classic. Some of them are still hanging on to their original view, because they’re afraid they’ll be called on it otherwise. Farty old guys like Andrew Sarris and Stanley Kaufman, who jointly have written maybe half a graceful sentence in their entire lives, will still say, ‘I still don’t like it and I don’t like the remake either!’ But most people think people will forget and they reassess and think they won’t get called on it. Or they assume, if they’re real young, that people loved the movie when it came out, which is far from the case.

Q: Is there a project you’re working on right now?

Toback: I have three movies I’m working on, and one of these days I’m going to put a gun to my head and figure out which one I’m going to do.

Q: Is it that they’re all similar?

Toback: Two of them are similar, one is very different.

Q: Is it that you’re being indecisive or is it that the funding isn’t coming?

Toback: No, I don’t think I’ll have any problem getting two of the three funded in a day. The third one might be a problem because it’s more expensive than the other two. I have just not been ready to say I’m ready. I’m very fast once I get ready, I’m demonically fast. But I bide my time in the meantime.

been ready to say I’m ready. I’m very fast once I get ready, I’m demonically fast. But I bide my time in the meantime.

Q: What is it that making a film takes out of you? Do you need to go into hibernation after making a movie?

Toback: I have to drift and cruise for a couple of years. What it takes out of you is not so much the physical labor – you can get refreshed in a week or two – it’s the vast absorption of inventive, original creative energy. If you’re a hired hand, which 95% of movies for good or bad are made by: here’s a script, will you direct it? You go in, direct the movie, you have an editor and you move on; you’re already planning your next movie while you’re shooting that one, or you already know what your next three movies are. That you can’t do if you’re making movies in an intensely personal way from your own experience. It’s just a much longer process. And it’s much more absorbing of psychic and inventive energy?

Q: Is that energy harder to come by the older you get?

Toback: That’s an interesting question. I haven’t thought about it. On the one hand I would say no, or I wouldn’t have been able to make When Will I Be Loved in 11 days. It would have been impossible. No, it’s not that I would say that – what I would say is that I’m not going to be rushed. When I made a couple of movies I think I’m always so aware of death being right around the corner, which it turns out since I’m 61 it hasn’t been (even if I died today I could hardly say it was around the corner). But when I was 26 and I thought it would be a miracle if I lived to 30, there was a sense of what if I die and I’ve only done this or this or this. Somewhere along the road, probably in the last four or five years, it occurred to me that even if I did die, I wouldn’t feel defeated. There are movies I still want to do, but I don’t feel that pressure to do something next so that I will not in my last second, if I’m still conscious, say, ‘Oh fuck, I can’t believe I didn’t do more than that.’