To a certain kind of person the name Will Shortz really means something. He’s the guy who’s responsible for the New York Times crossword puzzle, the single greatest puzzle on Earth. I’ll see people on the subway doing the puzzle in other papers (or worse, soduko or however it’s spelled) and I scoff – the Times is the puzzle by which all other puzzles are judged. It’s literate, it’s witty, it’s hip, and it gets harder every day. I can solve through Thursday – Fridays and Saturdays I don’t even bother.

To a certain kind of person the name Will Shortz really means something. He’s the guy who’s responsible for the New York Times crossword puzzle, the single greatest puzzle on Earth. I’ll see people on the subway doing the puzzle in other papers (or worse, soduko or however it’s spelled) and I scoff – the Times is the puzzle by which all other puzzles are judged. It’s literate, it’s witty, it’s hip, and it gets harder every day. I can solve through Thursday – Fridays and Saturdays I don’t even bother.

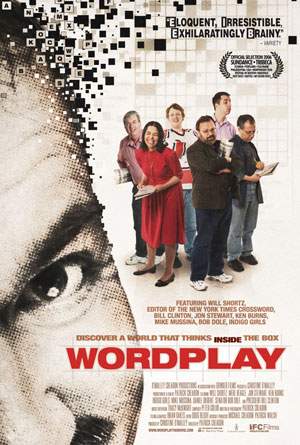

Wordplay is a documentary that delves into the world of Will Shortz, taking a look at the New York Times puzzle, the people who solve it (including celebrities like Jon Stewart and Bill Clinton), and the annual crossword puzzle tournament he’s been running for the last 29 years. Wordplay is a great film not because it sheds light on how puzzles are made or because it has celebrities expounding the virtues of the puzzle; it’s a great movie because it profiles these eccentric and lovely people who are the best crossword solvers in the country, people who tear through a complex crossword in four or five minutes. The twists and turns of the tournament creates an incredible level of drama and heartbreak. Who would have thought a movie about crossword puzzles could make you tear up? Wordplay does just that.

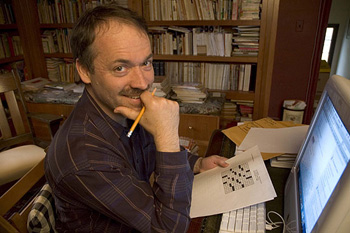

Will Shortz, editor of the Times puzzle, and Merl Reagle, one of the most highly regarded puzzle makers in the country, sat down for a press day to promote Wordplay this week. Shortz is tall and a little deadpan, while Reagle is Ricky Jay. Seriously. If you told me that Ricky Jay makes puzzles under the nom de crossword Merl Reagle, I would have no problem believing you.

Wordplay opens today in New York and comes to the rest of the country in the weeks ahead. I can’t recommend this movie enough; it’s the most exhilarating and illuminating movie of the summer.

Q: I can’t do the Friday or Saturday puzzles. I get angry at them. Do you get more hate mail as the week goes on?

Shortz: No, I think people know Friday and Saturday are tough so if they can’t do ‘em either they keep banging their heads against the wall or they stop.

Q: The director didn’t show you the movie until it was done. Did that make you nervous?

Shortz: No. I wasn’t nervous at all. I had no control over this at all. The first time I saw it was at the end of September, beginning of October last year, when he submitted it to the Sundance Film Festival. So I got to see what he was sending to the Festival. Of course I was flattered and honored, number one. Number two I was blown away by how good a film it was. I’m very lucky and all of crosswords are very lucky.

Reagle: Unbelievable job filming the unfilmable. Not exactly the most photogenic thing in the world, but he took the approach of filming the people and seeing how we got this way.

Q: How did this whole project start?

Reagle: Patrick Creadon and Christine O’Malley, the producer, are crossword fans. They even did the New York Times crossword on their honeymoon.

Shortz: They get up to Wednesday.

Reagle: They can do Wednesday and almost Thursday now.

Reagle: They can do Wednesday and almost Thursday now.

Shortz: Almost Thursday.

Reagle: But they’re crossword fans, and they thought, ‘Has anybody ever done a movie about this?’ They called Will and nobody had done anything about it. They’ve done spots – we were on Nightline once.

Shortz: There have been lots of short things, but no one has ever done a 90 minute film on crosswords. Besides the fact that they thought it was a fascinating subject and they thought there would be a hardcore audience for it, I think they were attracted to the challenge of it. How do you do a feature film on something that’s completely cerebral and that has no inherent drama and excitement.

Reagle: And that people mostly do by themselves.

Shortz: How do you do a whole film of people hunched over tables?

Reagle: All their friends and experts in the biz told them not to do it, and that made Patrick say, ‘Wow, I should do it.’

Shortz: That’s like when the first crossword book came out in 1924. Simon and Schuster were the publishers of it, and it was their first book and it was the world’s first crossword book. Just as they were about to come out with it all their friends and colleagues said, ‘Don’t besmirch your name.’ They took their name off the title page until the book became a best seller.

Reagle: It sold 400,000 books the first year. It was a runaway success. They called themselves Plaza Publishing early on, that was their phone exchange. But after it became this killer best seller they put their name on it.

The big question is how did Patrick think this would have any accessibility at all?

Shortz: He had a game plan. He had the whole film planned out. The one surprise was that the tournament was going to be a much smaller part of the film. It was going to be about me and the crossword world; once the tournament ended the way it did, that became the second half of the movie. The movie would have been good before, but that’s what makes it great.

Reagle: He had shot all the people beforehand, the eight or nine people were all filmed before hand with the promise that he would shoot the ones most likely to make it to the final, and he was lucky that three of them did. He didn’t do any shooting of them after.

Shortz: There’s no fakery.

Another bit of careful planning was that he wanted to see crosswords from the solver’s viewpoint, and the most interesting way of doing that is with celebrities. So he had the idea that somebody – and it turned out to be Merl – would create a puzzle for the Times, which you see me accepting (I don’t usually take puzzles by fax, but since Patrick was there filming that day, that was how we did that), and then he took it around to all the celebrity solvers.

Reagle: Ken Burns, who is a New York Times crossword fan right off the gun, said even if no one sees this I’m going to be in your movie. He was the first celebrity to sign on, and then there was the famous story about trying to get Jon Stewart and Bill Clinton – he had a hard time getting both of those, especially Jon Stewart, who has a very pugnacious agent who doesn’t let anybody get past him to get to Jon.

Shortz: Jon never even hears about the things he’s asked to do.

Reagle: They couldn’t get him but then there was a guy who came to the tournament for the first time in his life, a guy named Vic Fleming, who is a judge in Arkansas who wants to be a puzzle constructor, of all things. He sent puzzles for me to critique about three years ago, and so I critiqued him, and after a year and a half he was getting pretty good. So he decided to come to the 2005 tournament; he comes to the tournament, runs into Christine, and Christine says, ‘We’re having a hard time getting some of the celebs, like Bill Clinton.’ He says, ‘Hard time getting Bill? He’s one of my best friends!’ Arkansas judge! Vick and his wife have babysat Chelsea in the White House!

Vic gets a hold of Bill, and now Bill is in, so now they call Jon Stewart’s guy back –

Shortz: We now have Bill Clinton, can we get Jon Stewart? An hour later he called back and said, How about Thursday.

The last person to get added was Bob Dole. They had asked Bob Dole all through the spring to do this and his office had said this is not a good fit, and what turned it around at the very end is Bill called Bob Dole and said you have to be in this movie.

Reagle: Bob Dole told Patrick he had a hell of an advance man.

Q: You talk about how there’s no drama, but there is in the tournament.

Shortz: It’s not something you would think there is drama in, but there is, especially in the tournament. They lucked out by filming at the most exciting year in the 28 year history of the championship.

Q: That was my question – that was the biggest nailbiter in history?

Shortz: We had a couple of great ones before, like the year Ellen Ripstein won, and you see bits of that [in the film]. That was great. That wasn’t so much a nail biter – well, it was. Yeah it was, because Patrick Jordan had missed a letter. But with the twist at the end… [the rest of this is removed because I don’t want to spoil a great film]. Then to have a 20 year old [competing on a finalist level]; that’s just fantastic. He’s a normal guy, loves sports, drinks, plays video games. A lot of people have an image of crossword solvers as being nerdy brainiacs and while there are some people like that I don’t think that’s representative of crossworders as a whole, and certainly Tyler is not like that.

Yeah it was, because Patrick Jordan had missed a letter. But with the twist at the end… [the rest of this is removed because I don’t want to spoil a great film]. Then to have a 20 year old [competing on a finalist level]; that’s just fantastic. He’s a normal guy, loves sports, drinks, plays video games. A lot of people have an image of crossword solvers as being nerdy brainiacs and while there are some people like that I don’t think that’s representative of crossworders as a whole, and certainly Tyler is not like that.

Q: The movie really opens up the secrets of the puzzle creation world.

Reagle: A friend of mine said after she saw the movie, ‘You know, I never even thought to think how you guys do that.’

Shortz: It’s like crosswords appear like magic. And if there is something that generates them, people think it’s a computer. You press a button and a computer makes a crossword – never thinking that there’s a human being behind It.

Q: There are some clues that I can see in the puzzle that are only crossword puzzle words – like obe, for “Japanese sash.”

Shortz: How many times do you run across obe in every day life? Almost none.

Reagle: It could be Obi Wan Kenobi.

Q: As a constructor when you have a puzzle where you’re throwing words like that in there… do you like having those words in the arsenal, or do you feel like the puzzle wasn’t the best?

Reagle: Emu and obe fall in the same thing. Obe is a common word in Japan.

Shortz: It’s a good word to know! It’s crossword-ese in the sense that it comes up in crosswords more than in real life, but you’ll come across it occasionally.

Reagle: It’s words like ern – no one even knows what they look like. Have you seen one?

Shortz: Anoa, it’s a Celebes ox. No one even knows what Celebes is. It’s an island in Indonesia.

Reagle: Animals like that we try to avoid. But obes –

Shortz: I don’t mind obe too much.

Reagle: Kimono. Everybody’s heard of that. It’s the sash that closes it.

Shortz: If you’ve ever seen a Japanese drama, if you’ve ever gone to a Japanese restaurant, you’ve seen an obe.

Reagle: The trouble with us is how to clue it interestingly. Japanese sash, kimono closer…

Shortz: Japanese tie.

Reagle: Japanese wrapper.

[laughs]

Sometimes you can go too far doing this, but we see the same words all the time. My personal worst one is Eli, because there are only like four Elis – the guy in the Bible, Eli Lilly, Eli Wallach and Eli Whitney.

Shortz: Now there’s the quarterback, Eli Manning. I was one of the first to run him in the Times crossword puzzle; he had only been playing a year and someone criticized me, ‘Who’s ever heard of Eli Manning?’ Fortunately he’s gone on to become an important player, so I was justified.

Reagle: His brothers are really famous. There’s also Eli’s Coming by Three Dog Night. You have blank, apostrophe, s, Coming.

Shortz: At least we have options for Eli. With anoa it’s Celebes ox. You don’t play around with that.

Q: You mention that the image of the crossword solver is nerdy, but we do see a lot of that at the tournament.

Q: You mention that the image of the crossword solver is nerdy, but we do see a lot of that at the tournament.

Shortz: There is a nerdy element in crossword puzzles. If you know a lot of stuff and you’re very wrapped up in a mental activity, there’s going to be nerdiness. But to be a good crossword solver you have to know a little of everything. You know the classical subjects, movies, TV, rock and roll, opera, classical music. It helps to have a flexible mind, you have to have a good sense of humor to be a good solver. Nerdiness will only take you so far.

Q: I’m fascinated by the final round in the tournament, where they stand in front of a crowd and solve the puzzle on a huge board. It’s such an alien environment for puzzle solving – did people complain when you first introduced that?

Shortz: The first year people thought it would be weird or difficult. But actually the people who have done it say they feel pretty comfortable up there. They have the headsets with white noise – it’s actually a tape of a huge party at the United Nations, with people speaking in many different languages. You put the headphone on and there’s the soft murmur of a party going through your ears, allowing you to concentrate on the puzzle. It’s true you’re standing up, it’s true you’re working with a [huge] pen and you’re doing it in these big squares with all these people watching, but I think it makes for good drama.

Q: The film talks about the rules of puzzle making – no unchecked letters, symmetry of the grid design, no word islands – but every now and again you do some avant garde stuff in the puzzle. Sometimes you’ll have three letters in one square, and I remember puzzles with symbols instead of letters. How do you decide when it’s time to throw one of those at us?

Shortz: I try not to do it too often. If I did it last week I won’t do it for another few weeks, but I like every Times crossword to have a little surprise.

Q: You know you’ve made it when you’re in the Times crossword puzzle. Do you ever hear from celebrities whose names you use?

Shortz: It’s from the mid-level celebrities. It’s not the really famous people because they’re jaded; it’s the mid-level celebrity whose name appears in the puzzle for the first time and it’s like validation of their existence, and I’ll hear from them.

Q: Do you guys ever use your own names as words?

Shortz: No, we’ll never clue ourselves.

Reagle: Sometimes I’ll use Merl; it’s a real crossword word.

Shortz: But you’ll clue it as the bird.

Reagle: ‘Puzzling bird.’ That could be me too!