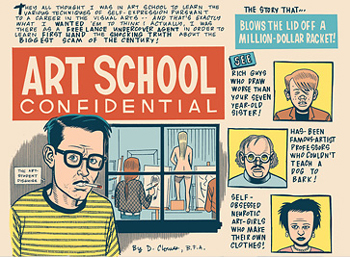

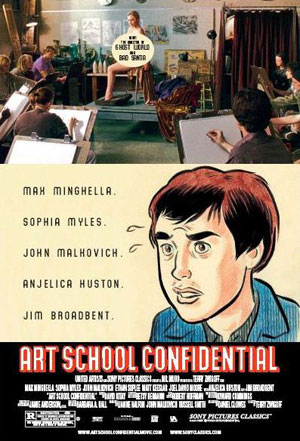

Art School Confidential reteams the Ghost World duo of director Terry Zwigoff and writer/cartoonist Dan Clowes. Clowes is much beloved in the alternative comic world for his glorious book Eightball, which has always been among the most accessible of the non-mainstream comics.

Art School Confidential reteams the Ghost World duo of director Terry Zwigoff and writer/cartoonist Dan Clowes. Clowes is much beloved in the alternative comic world for his glorious book Eightball, which has always been among the most accessible of the non-mainstream comics.

It’s interesting that life has taken Clowes to Hollywood – he’s currently writing the film about the kids who remade Raiders of the Lost Ark, shot for shot, in their back yard – because back in the hey day of the alternative comics scene it just didn’t seem all that plausible. Maybe I should have seen his work for OK Soda as a sign of his impending sellout. Just kidding! What’s great about Clowes is how he’s been carving out a spot in Hollywood for himself without selling out.

I spent some time talking with Clowes at the Regency Hotel in New York City a couple of weeks back. It was one of those interviews that spoils you for the rest of them – easy, conversational, friendly and funny. I only indicated that Clowes is laughing a couple of times, when the jokes felt too deadpan to come across right in print, but on the tape he’s laughing a lot. And so am I.

I wish I remembered how this conversation started – the genesis of it comes before I turned my recorder on, so all I have is this seemingly odd non-sequiter from Clowes.

Clowes: Have you seen that TV show where they have the people with the white make-up…

Q: Black/White? No, I haven’t. Have you?

Clowes: Yes. And it’s just shocking.

Q: Somebody told me that it crosses the racial divide by showing you that people of all races are horrible.

Clowes: Yeah. My wife and I can’t decide who we hate more.

Q: But you can’t stop watching.

Clowes: I can’t. It’s so sick. I keep thinking it’ll be erased from the annals of history and people will go, ‘What are you talking about? That never aired.’ It’s so close to a minstrel show, there’s something so wrong about it.

Q: Is Hollywood stealing Dan Clowes from the comic book world? The 21st century hasn’t been the most productive for you on the comic front.

Clowes: No, but I have to say that I think I would have been just as unproductive without it. Maybe even more so in a way. After 15 years of drawing Eightball I hit this thing where I just felt like, ‘I need to actually leave the house.’ Knowing many cartoonists who are ten years older than me I realized every one of these people are insane. I love them all dearly, but after a while you can tell – they talk to themselves and they become very paranoid. It’s like being in prison to some degree; you’re in solitary confinement. You can’t do it except in a room and you have to concentrate. You have to have quiet. It’s not like in Chasing Amy  where they have backwards baseball caps and high five over the drawing board – that doesn’t happen.

where they have backwards baseball caps and high five over the drawing board – that doesn’t happen.

So to me it was a very good thing to have something, whether it was movies or getting a job at Burger King, just something to give me another perspective. And it makes me love the comics all over again.

Q: Is drawing something you have to do daily anyway?

Clowes: I do it every day. I used to do it for five or six hours a day, and now it’s about three hours a day, but I do it without fail every night.

Q: When there’s not some kind of a deadline or a new book looming do you feel free to go off on weird tangents?

Clowes: I do a lot of stuff that nobody will ever see. Sketchbook comics that don’t go anywhere, or I have grand, huge ideas that take months and months to play out and then I realize how retarded they are and they never go anywhere.

Q: There’s something about Jerome, who is an artist who is deeply uncomfortable in the art world, and he goes to a school that’s an awful lot like the Pratt Institute, where you went to school – is Jerome you more than any other character?

Clowes: He’s to some degree the younger me. I never wanted to be the kind of artist he wants to be – I never wanted to be a fine artist. He sort of wants to become Picasso at some point and reinvent the art world. I had no real interest in the art world. I had no interest in showing at a gallery, that was not anything I ever thought about. I really wanted to learn the basic principals and techniques of drawing comics and there was nobody there who knew that stuff. I was saying to somebody earlier it was like going to school to be a zoologist and having them say, ‘Well, in astronomy we do this…’ I remember thinking that maybe those relate, and in retrospect I can see that if you are a zoologist maybe you can learn from astronomy, maybe things correlate. In my case, looking back, I can see the things that make a good sculpture have a lot to do with what makes a good structure for a narrative, in a way. But I couldn’t see that at 18, and I don’t think anybody could. I think now I would probably benefit more from going to art school.

Q: Pratt’s interesting. I live near Pratt –

Clowes: Where do you live?

Q: I live in Prospect Heights, right by the Brooklyn Museum of Art.

Clowes: That’s nice there.

Q: I love it there. But Pratt’s interesting because it’s this enclave of white kids dropped into what is essentially a black neighborhood –

Clowes: An angry black neighborhood.

Q: And you kind of touch on that in the film, but what was your experience like? Now the area has changed a bit, but I imagine when you were in school it was different.

Clowes: Now it’s not so bad. It made you sort of fight for your own art. You would have to carry your ridiculous sculpture for eight blocks through the catcalls of kids who thought you were the most ridiculous human being. There’s something sobering about that, it’s like these are the real people, this is the general public out there, and they’re telling you you’re an idiot. And they’re willing to stab you for it. I think that was a good experience; it made me not want to carry the ridiculous sculpture down the street and maybe do things that, if they found it, maybe they would think it had some validity to it.

Q: Is that what drew you to comics, that they’re more egalitarian?

Clowes: To some degree. I was drawn to comics certainly before that. But I can remember having done some self-published comics when I was 18, 19 years old and I was on the subway with friends when some really scary mugger kids came over to us and said, ‘What’s that,’ and grabbed the comic away from us. Later we saw them reading it and they were cracking up. We were doing these punk comics, so it was this amoral thing where every character gets murdered and there’s no retribution for the killer. There was something amazing about these guys crowding around this stupid self-published comic and cracking up; these guys who were probably murderers themselves.

character gets murdered and there’s no retribution for the killer. There was something amazing about these guys crowding around this stupid self-published comic and cracking up; these guys who were probably murderers themselves.

Q: This may be too much sharing, but I have recently been dating this girl I met on an internet profile site. Her headline, which caught my eye, was ‘A Grown-Up Enid Coleslaw’.

Clowes: Well you can thank me for that.

Q: Thank you very much, I had a great weekend. Anyway, the point is that people so identify themselves with your characters –

Clowes: Especially that one.

Q: Especially that one. Your work has turned into a pop cultural thing. What is that like?

Clowes: That is very recent, certainly since Ghost World. Somebody will throw my name around in an article, as the creator of a certain type of character that I don’t quite see. There’s actually – I’ve never read any of his work – this guy James Patterson, who’s like the number one selling thriller author, and apparently in his new book there’s a line, ‘He looked like something out of a Dan Clowes graphic novel.’ But then the description is ‘pimply faced, greasy haired freak.’ That was kind of shocking. I learned about it from my publisher’s mother, who is 85 years old and reading the book. That means something, I don’t know what.

Q: Why do you think it is that Ghost World has struck such a chord?

Clowes: I’ve thought about it many times and I can’t quite put my finger on why that one is so different from the other ones. That’s the one – every month I can count on Ghost World selling more copies than my other books times five. I guess everybody in the world was that age, and had that set of feelings to some degree. That’s all I can say. Because it’s not just girls. But I have no idea. At the time I didn’t feel any differently about it than anything else.

Q: The experience of being nominated for an Oscar for that film – that’s got to be weird. You’re working at a small black and white publishing company and then you’re suddenly at the Kodak Theater. How is that? How mind-blowing is that? And now is it something where you think, ‘Next time I’m at the Oscars…’

Clowes: I knew it was a weird anomaly. It’s funny, I was thinking the other day that it was so in a way so meaningless to me. It wasn’t anything I had a stake in, I knew there was no way we would win. It was just, ‘Oh I get to be in a room with Ron Howard.’ [laughs] It was a very odd experience.

But I wasn’t that nervous until the very last minute. When Gwyneth Paltrow said, ‘And the Oscar goes to…’ I thought, ‘What if I win? I’m fucked! I have to go up there in front of four billion people.’ But really right up to that moment it was just funny and I was thinking that I was much more nervous when I won the Harvey Award in 1991 and I had to go up in front of 13 comic geezers. I was trembling. That says something about how far I’ve plummeted as a human being.

Q: Did you really not think you would win? Everyone says that, and they say that being nominated is the honor, but I know if I was nominated in the back of my mind I would be planning how I would deal with winning.

Clowes: If the other nominees… you see, there are these other awards before the Oscars, there’s the Golden Globes and the Writer’s Guild and the Blah Blah Blah and the Yak Yak Yak, there’s hundreds. The same guy won every single one. Akiva Goldsman won for A Beautiful Mind. He won every single one. If it had been all over the map, maybe we would have thought this would be our time, but we just knew he was going to get it.

Q: It was a lifetime acheivement thing. They were rewarding him for his work on Batman and Robin.

Q: It was a lifetime acheivement thing. They were rewarding him for his work on Batman and Robin.

Clowes: Yes, his fine work on Batman and Robin and Lost in Space. [laughs]

Q: You’re writing Master of Space and Time.

Clowes: That’s something I’d like to do at some point, but it’s not a real project yet. It’s not set up at a studio or anything. Michel Gondry called me up and I came out to New York and we hung out for a while and I’m very interested in doing it, but it’s not the next thing either of us are doing. But I’d love to do it.

Q: That’s based on a novel. You’ve adapted your own stuff; have you considered how you would adapt someone else’s stuff?

Clowes: No, and that’s the problem. It’s a completely crazy novel. That’s what I like about it and what Michel’s liked about it – Michel’s owned it for 20 years, I think. He’s just crazy about the weirdness of it and I think a studio’s never going to be crazy about it. We could just make it except that it’s a huge sci-fi film that would cost a zillion dollars. It’s got to be something different from the book, I think. And it’s the kind of premise you could do lots of things with, almost too many. We never got to the point where we felt ‘This is what we can do, let’s go pitch it.’

Q: Do you give advice to other comic folks who are being courted by Hollywood?

Clowes: I try to, if it’s my crowd in comics. If they’re outsiders, if they’re superhero guys, I just say I don’t know how to deal with that. But if it’s somebody in my little world I try to help. I find almost always that it’s somebody who’s not a real filmmaker, where that’s their entry to getting meetings – they want have a property and use that to become a filmmaker. I make sure these guys don’t get suckered by that; you get tied up legally for years and then some real filmmaker comes along and you’re stuck.

Q: What else of yours has “heat,” as they say in the business? Are there other properties that have been optioned and have heat?

Clowes: I’ve never optioned anything of mine that I don’t think I could do myself. I hold that out as something if, I ever needed to make money for some reason, I could do, but for now I would rather control everything. So I get a lot of offers for David Boring and stuff like that, and that’s not something I want to write – I don’t see how you would do it as a movie – and I don’t want somebody else to try it. If I can’t do it, I can’t see somebody else being able to.

Q: So you would never option something off for someone else to write?

Clowes: If somebody cool came along… if David Lynch came along, sure, in a minute. But I wouldn’t option it to an actor – who is usually who wants it – or a producer, because they could just hand it to anybody. It would have to be to the real creative people involved.

wouldn’t option it to an actor – who is usually who wants it – or a producer, because they could just hand it to anybody. It would have to be to the real creative people involved.

Q: That happens a lot, where actors come to you?

Clowes: It happens a lot especially with something like David Boring. It’s really about a 23 year old guy, and they look at it and go, ‘I could be this guy,’ but don’t think of how it could be made.

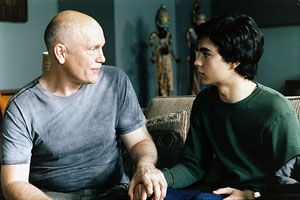

Q: I asked Max Minghella about the idea that every artist uses his art to get laid. Is that fair? I’ve read that every rock and roll song ever written was an excuse to get laid.

Clowes: I think that’s probably true. And certainly I was in college it dawned on me that I should have gone into rock music rather than comic books [laughs]. I used to be at these rock shows and wonder, ‘Why do they love him? He just plays the bass! Here I can draw all these pictures and tell a moving tale with words and pictures!’ It’s still sort of baffling to me. But people respond to that showy, that display of manhood. Comics don’t exactly do that.

Q: Correct me if I’m wrong, but comics have done well for you – you met your wife at a signing.

Clowes: It was sort of inadvertent; she was getting something signed for her ex-boyfriend. They had just broken up and it was this kind of conciliatory gift. She had no knowledge of my work at all, and actually harbored a distrust of it because she didn’t really like this boyfriend anymore. So I really had to win her over. It was more of just an odd meeting – she wasn’t the slavish fangirl people imagine.

Q: Who is your fanbase?

Clowes: I don’t know anymore. I used to know. Back in the pre-email days I used to put out an issue and I would get letters; I would get many, twenty, thirty letters a week. It was an art schoolish 18 to 25 year old crowd who like a sort of alternative culture. They weren’t going to mainstream movies, they were the people who were seeking out the kind of culture that was very hard to find before the internet. I could see them a mile away if I was at a comic convention – ‘Here comes one of mine.’ Now I do signings and I think it’s these people to some degree, but they’re older. They’re 35. And they’re pretty cool – I think there’s something to be said about having a group of readers you’d want to hang out with because I’ve actually signed books next to guys who draw for Image Comics and they just have a row of surly looking 13 year olds. I think, ‘Boy that would not be fun.’ I would have such contempt for my readers. Pretty much everybody who gets a book signed by me, I think ‘I could have dinner with this guy.’ But I don’t know where they’re coming from or how they know about it.

Q: I’m assuming you’ve done cons since Ghost World –

Clowes: I’ve done almost none. I did the MoCCA last year and that was the only one. I’ve done signing tours, and that’s kind of a different crowd than a comic con crowd. I’m going to San Diego this year; I kind of figured I should probably go and promote whatever version of this movie exists.

Q: That’s a weird event.

Clowes: I used to go years ago when it was in a hotel room and it was 50 guys. Last time I went it was insane and I have been told it’s exponentially crazier.

Q: I was there last year. It’s impossible because the floor was so many football fields long.

Clowes: It used to be that you could see from one end to the other. You could just say, ‘I’ll meet you at the con.’ You didn’t have to be Table A-37.

Q: What’s funny is that San Diego has gotten so much bigger, but the world of comics…

Clowes: It’s about the same.

Q: Alternative comics, for lack of a better term, had their heyday in the early 90s. Where do you think they are now?

Clowes: I think they migrated into the regular publishing world. I think the kind of stuff we’re doing is the stuff that editors at the real publishing houses respond to. We were talking about how everybody has a movie deal – now everybody has a publishing deal. I thin that’s ultimately going to be even more detrimental because I think there’s going to be a lot of books that just won’t sell and nobody will want to do them anymore. It’s unfair to the books that would sell.

Q: So you think the new focus on straight publishing houses is a bad thing?

Clowes: I don’t know that it’s a bad thing, but people are getting advances that are far beyond what I know these things will sell. I’ve been doing this a long time and I can tell within 5000 copies what these things will do. I don’t think they have a clue, they’re just, ‘Graphic novels!’ and they don’t have a sense of the market.

Q: It’s interesting because the direct market is disappearing, which was your bread and butter.

Clowes: For years. We had to make sure these stores ordered us.

Q: And now it’s turning into the Barnes & Noble. Is that where you’re aiming your stuff?

Clowes: I try not to think about it. I figure there will always be something, some way to buy it. Maybe I’m totally wrong. You go into a mainstream bookstore and there’s this little ghetto of Maus and Jimmy Corrigan. I see stuff like Persepolis has sold very well, and I think that has almost nothing to do with what I do and yet it’s still part of this little niche.

Q: They often stock Persepolis in the straight fiction section.

Clowes: They do. And they often put Maus in the Judaica section. But once you get enough of these things and there’s a bit of a mass, you get your own place.

Q: Did you think that comics would occupy a different place by now? They seemed to be picking up speed as a real form of literature for a while – Maus is a good example – and it looked like people might realize comics aren’t just about superheroes. Do you think that’s still happening?

Q: Did you think that comics would occupy a different place by now? They seemed to be picking up speed as a real form of literature for a while – Maus is a good example – and it looked like people might realize comics aren’t just about superheroes. Do you think that’s still happening?

Clowes: It’s certainly happening more than when I started. I’m ambivalent about it too – I sort of enjoyed being ignored; it gave us something to bristle against. You felt no pressure at all doing comics – my readership was like 25 year old guys who were in a band, and those guys are not hard to entertain. I felt like anything more I could get in than would entertain them was purely for my own amusement. Now you finish something and you send it off and you realize, oh my God, this is going to be reviewed by the New Yorker or something. That’s a very different feeling than just knowing it’s the same doofuses you see every week at the bar, face down on the floor.

Q: How do you think your fans will react to you moving into straight screenwriting with the Raiders of the Lost Ark movie? Will they see it as selling out?

Clowes: I hope they’ll wait until they see the film. Of course, as a screenwriter, you have no control over the final film, but as script it’s very much one of my things. It’s almost right out of an Eightball in a certain way. I’m just hoping that they’ll reserve judgment until they actually see it, which is asking a lot out of people these days. They don’t do that much, and then of course when it comes out you never hear anybody apologize for the conclusions they leapt to. Before Ghost World came out we heard nothing but ‘This will be the worst movie ever made.’ And then never heard from those people again.

Q: Are you surprised to see Scarlett Johanssen get named Sexiest Woman of the year?

Clowes: I’m actually not. The minute we met her – I remember early on in Ghost World Terry and I were invited out to dinner with these British producers, these very rich and very adult people. We invited Scarlett along to take the heat off of us. After five minutes Terry and I are talking about some inane childish thing and this 60 year old woman and Scarlett are talking about the best sushi places in London. She’s 15 or 16 at the time and she just could carry herself so well. If I could have invested in her at the time, I would have.

Q: You have this record of who you are for the last two decades in the form of your work. Do you ever look back and compare yourself now to who you were?

Clowes: I’ve finally gotten to the point where it’s so separate from who I am now that I’m not mortified by it and I can look at it and appreciate the twisted young man that I was. I used to look at the artwork for the early Eightballs and think, ‘That’s so crude and weird,’ but now I appreciate it on a certain primitive level. [laughs] But it doesn’t feel like it’s me. I’m not looking at it wondering ‘What was I doing?’ It’s the record of an odd young man.

Q: What would that odd young man think of the man you are now?

Clowes: I would hope that this is sort of what I imagined I would be doing.

Q: So you’re happy.

Clowes: I hope so. I’m not happy with what I do, but I’m happy with how things turned out.

Q: You’re not happy with your work?

Clowes: I’m always slightly disappointed in myself and wish I could do it over again.

Q: What’s the best thing you’ve ever done?

Clowes: Maybe Death Ray, in the last Eightball. That was the closest I’ve felt to, ‘Wow I got what I set out to do on paper.’ Usually I set out to do something and it turns into something else. That one I knew what I wanted to do and it got there.