Last week I headed over to Newark International Airport to see the last day of principal photography of Paul Greengrass’ 9/11 film, Flight 93. It was a great opportunity to finally meet Paul, with whom I spent a number of hours on the phone in 2005. Paul’s one of the friendliest, most gregarious people of any profession I have met – he would keep talking to me even as his next shot was ready to go.

There’s more to tell you about the visit in a fuller report, but I want to let you know now that after meeting the actors and crew I have no doubt that Flight 93 is going to be a serious, harrowing and non-exploitative film that can really bring the events of 9/11 back into discussion without the jingoism, sloganism or reflexive posturing on both sides of the ideological aisle that came in the days after. At it’s heart, I think Flight 93 is New Journalism, the cinematic heir to Tom Wolfe.

The interview here was conducted via telephone at the end of 2005, when the production was at Pinewood in England, where the actors spent their days in a tube of a plane set. You can read the first part of the interview, which took place a few days prior to this one, here.

When we started off, Paul wanted to touch on Watchmen again, a subject we had tackled last time. (As of last week, when I visited the set and spoke with Paul and Watchmen and Flight 93 producer Lloyd Levin, Paul is off the project)

Greengrass: There’s no doubt in my mind that Watchmen will be made. And I really hope  it’s me. That’s where I’m coming from. I did believe in that film a lot, and I do believe in it. And I believe in those things that we talked about, about a film of Watchmen being relevant now.

it’s me. That’s where I’m coming from. I did believe in that film a lot, and I do believe in it. And I believe in those things that we talked about, about a film of Watchmen being relevant now.

I regret it. It’s really a shame. It would have been a fantastically timely film, but it’s time will come. No doubt about it. I hope it’s me, but when you’re in the middle of a new film, which I am now, it’s impossible to think about it. And that’s where Lloyd and I have left it. I’ve parked it in my mind for a bit while I do the one I’m doing.

Q: But you have one coming up right after the one you’re doing, don’t you? Is Bourne next after Flight 93?

Greengrass: We’re talking about it, me and Universal. We’re discussing it, when it might be, all that’s sorts of things. That’s another film – I would like to do that film too, because I believe in the Bourne franchise. It’s a happy position to be in – you’re always looking for things that are in your register. If you’re a singer, you’re looking for things that are in your register, things that you can sing. The interesting thing is that all three of those films, Bourne Supremacy, Flight 93 and Watchmen, they all appeal to different parts of me, but they’re all clearly within the same register. They’re all gritty, and they’re all one way or another about today.

[Note: As of last week Paul confirmed he will be directing The Bourne Ultimatum, starting pre-production three days after Flight 93 is released]

Q: I would include Bloody Sunday in that as well.

Greengrass: Flight 93 is very much like Bloody Sunday – it’s being made in a similar way, and in a sense it’s one of those films where you just go, ‘I should make that film.’ I spent a lot of time over the years, going way back to the very beginning, making films about terrorism. What it’s about, what it means, why it happens, what we can and can’t do about it – all of those sorts of things. Most, if not all of those, have been within a context of Ireland, but the lessons do travel. There are truths about these things. That’s the interesting thing about Flight 93.

The point about true stories is that they tell you something very simple or profound about the way the world is, because they’re true. They really happened. That’s not to decry fictional stories, because they can tell you also profound truths. I suppose if you’re somebody from my background you’re going to be drawn to factual material, maybe, abd be more confident with that sort of film than maybe another director might be. To me the challenge of Flight 93 is to get the right tones, first off.

The issue we were talking about last time was, when is the right time? Nobody is going to come up and say, ‘It’s the right time to make a film about 9/11.’ In a sense you’re always going to have to put yourself forward and say, I think it’s the right time to tell the story. And in that sense it puts a responsibility on your shoulders. I feel it. You have to be right in that judgement. If you’re wrong, and it’s not the right time, then it’s a mistake. But I do feel – and I’m speaking as someone who’s done a few kinds of these films a time or before – I do feel it’s the right time. And I’ll tell you why: I think it would have been the wrong time to make this film before the publication of the 9/11 Commission Report. In a democracy it’s important that the first step in asking what happened and what it means is that the people’s representatives have got to speak.

What they’ve done is put a tremendous amount of material into the public domain – frankly I think it’s an impressive document. There are always going to be conspiracy theorists who want to shoot it down. But believe me, if you’ve looked at the problems of terrorism in our society in Ireland and how it affects the democratic process and poisons it and damages it, because it makes you overreact, it makes societies contract and become more secretive and more open – all those things I’ve seen at first hand myself in the context of Britain and Ireland. And they’re being played out on a much larger scale post-9/11. But! But there’s no doubt in my mind – and I’m not saying it’s a perfect document – but having read it and having much of the supplementary material, I’ve studied that report in detail – that was an admirable report and that was an admirable process. I don’t believe, personally, I don’t buy the deep conspiratorial line. But then it’s not a line I’ve bought in my life either. I didn’t buy the deep conspiratorial line on Bloody Sunday. I don’t believe in those kinds of conspiracies – I’m not say there aren’t conspiracies and that conspiracies don’t happen. I am saying that they are far fewer and more mundane than conspiracy theorists want to believe.

say there aren’t conspiracies and that conspiracies don’t happen. I am saying that they are far fewer and more mundane than conspiracy theorists want to believe.

Q: So you discount the theory that Flight 93 was shot down.

Greengrass: I do. I don’t believe that was the case. In fact I will go further and say I know that’s not the case.

The way you have to look at conspiracies, it’s always seemed to me, is that you can look at the evidence, all the pieces of evidence you have to look through. I looked through all of them, the wreckage, the white airplane that was allegedly seen – all the pieces of evidence that is put forward by the conspiracy theorists. But in the end what I think you have to do is ask yourself a different question, which is let’s assume for the sake of argument that the conspiracy theory was correct. Then you ask yourself this question, which is the most important question of all conspiracy theories: ‘Assuming the theory is true, how many people would had have to have known for that conspiracy to be active?’ And then when you’ve answered that question, ask yourself whether it’s plausible that that number of people could keep that dark secret. Is it, on a common sense level, likely to be true?

Let’s go back to Flight 93. Let’s assume that the conspiracy theories are true, that a US military aircraft shot this plane down. Let’s go through the hundreds of people who would have to know about that. First and most obviously would have to be the pilot, because he pressed the button.

Second, I would say 100% certainly, the other pilot who would have been flying with him at the time. Military planes fly in pairs, especially on combat missions, and the planes that were flying that day were flying in pairs. Then the next person who would need to know would be the person who was in command and control of that airplane. That airplane didn’t get there without being directed there. There’s got to be navigation systems, tracking and vectoring, all that stuff has to take place. You’ve got to assume that nobody tracking that airplane saw a radar signature or a missile signature. Then look at it another way – did that pilot act alone? Did the pilot take it upon himself to fire that missile that took that airplane down? No. He would have had to have an order, so somebody would have had to have given an order. We know how an order gets passed to a combat aircraft. They get passed through the relevant air defense unit.

So that needs to be passed through channels, and you can’t have an order given singularly by a person in a military unit. He would have to be on a net, there would have to be other people involved in that command and control system who would have to know. You’re in to the dozens and dozens before you even blink.

Setting all that aside, what happens when that aircraft goes back to base and there’s a missile missing? In the real world people load missiles and ordnance is very, very carefully controlled. You can’t just fire a missile and come back with an F-16 and expect nobody to notice. All the ordnance crews would have to know that missile would have gone missing. Straight off you’re into dozens of people there.

Then you’ve got to presuppose that all those people would not have covered their ass by getting approval from the next person up the line. The one truth about 9/11 when you study it is the sheer inertia of people finding it hard to deal with the challenge in real time up against the clock, and the continued desire to refer upwards. In the main – there were some exceptions to that. In the main, in military organizations, when crises happen, stuff goes up and down the line. It happens in most organizations, actually, and the bigger the bureaucracy, the more it’s true. What would be the likelihood of any person making the decision to shoot down a civilian airliner without making sure he has the authority from the next person above? The truth about 9/11 is that that chain went all the way up to Cheney, and then to Bush. The great problem they had on 9/11 was working decision-making up and down that line quickly enough to actually get that decision out in real time fast enough to intercept any airplane.

What I’m saying is that when you examine the numbers of people… The conspiracy theory is at root that presumably the president and the vice-president and some higher-ups in the military decided to shoot the plane down and then decided to keep it concealed from the American people. That’s the basic thesis, isn’t it? It’s not that a rogue pilot shot it down on his own. I mean, as if in a sophisticated military bureaucracy such a thing could happen and there would not be hundreds of people who would need to have known about it.

Q: I think what makes it so attractive to people is that the plane was up in the air for so long and it seems like nobody did anything about it. The conspiracy theory is more comforting than a system that doesn’t work.

Greengrass: Exactly. It answers a complex situation with a simple truth. It’s a simple answer to a disturbingly complex situation. But if you free your mind, I think, of the conspiracy theory, you’ll see something much more interesting. You’ll see how hard it is to act, not how easy it is. How imprecise information was. How difficult it was for all the ducks to be gotten in a row. How much gear crunching there was in the military and civilian sectors, just the full extent of the utter panic and confusion. The fog and the friction of the war. How difficult it was to track an airplane.  These guys who planned this operation, Sheikh Mohammed and Atta and all these guys, they weren’t stupid. They had years to plan this thing. They knew very well that if you took a civilian airliner and you had the will and the means to execute multiple hijackings and the technical capacity to turn the transponders off, they knew in effect those airplanes – particularly if they dived and turned as those airplanes did – in effect you were invisible on the air traffic control system. Literally the problem was to find an airplane that was no longer squawking in the midst of thousands up in the sky. It was a nightmare task. That was the problem.

These guys who planned this operation, Sheikh Mohammed and Atta and all these guys, they weren’t stupid. They had years to plan this thing. They knew very well that if you took a civilian airliner and you had the will and the means to execute multiple hijackings and the technical capacity to turn the transponders off, they knew in effect those airplanes – particularly if they dived and turned as those airplanes did – in effect you were invisible on the air traffic control system. Literally the problem was to find an airplane that was no longer squawking in the midst of thousands up in the sky. It was a nightmare task. That was the problem.

That’s not to say that there weren’t mistakes made, but in a sense you get some fundamental truth about terrorism. Terrorism is asymmetrical warfare. It’s the engagement of a vastly superior force by a vastly inferior but clandestine force. That’s how it happens. It’s looking for one person in a gigantic crowd with hostile intent. It’s looking for the one hostile aircraft in a sea of friendly aircraft. What happens when you try to do that is what Flight 93 is about. The truth is that, if you think about it in metaphorical terms, what is going on in the world today. And it asks all sorts of questions – how do we target these people and at what cost? What are the boundaries?

Q: Clear something up for me – are you going to be focusing on the people on the ground as well as the passengers in the plane?

Greengrass: Oh yeah, for sure. Absolutely, because one of the things you can see that’s most important about 9/11 is that what happened was during the course of two hours we moved from a civilian system to a militarized – we went to war. That’s the simple truth of it. Everything that has followed is a consequence of that.

We can oppose the War on Terror, we can have views on it, we can worry about its boundaries, or we can approve of it and want it to go further. It doesn’t matter where you are on the spectrum – we all know that it happened, and that it continues to this day.

We went to war, and that process, if you look carefully enough at Flight 93 on the ground and in the air, you can see that process happen across about 100 minutes. That, to me, is a much more profound and disturbing truth than a conspiracy theory. Conspiracy theory in the end makes of history men in black hats and men in white hats. History becomes the story of how the men in black hats did us down secretly. But that’s not the world that I recognize.

Q: Are you going to tell that story of the 100 minutes in real time?

Greengrass: Yeah.

Q: I noticed from looking at the cast list that you don’t have big name actors. Was that a creative, rather than financial, decision?

Greengrass: Yeah, because I want this film to be received for what it is, at a level of reality, not fantasy. I want you just to go eye level through 9/11, from that morning, and experience it as close as possible as if you were there.

So you see and can understand how it felt to be a civilian air traffic control grappling with the problem when the planes go missing. Or what it felt like to be a military commander when you’re drawn into trying to engage airplanes you can’t find. What it felt like, above all, to be forty ordinary men and women on an airplane when you face the challenge that we face today. ‘What are we going to do?’ Except that we have the luxury that we may have some time to think about it, or maybe it’s a decision we don’t have to make. Those people couldn’t duck it. They had to make a choice – whether to sit there and hope for the best or to do something and possibly face the worst. There were no easy answers, because the truth is that there aren’t any easy answers in the world we’re facing now. If a pre-emptive strike was the simple solution, it would have worked by now. Equally, if doing nothing was going to work by now, it would have worked.

time to think about it, or maybe it’s a decision we don’t have to make. Those people couldn’t duck it. They had to make a choice – whether to sit there and hope for the best or to do something and possibly face the worst. There were no easy answers, because the truth is that there aren’t any easy answers in the world we’re facing now. If a pre-emptive strike was the simple solution, it would have worked by now. Equally, if doing nothing was going to work by now, it would have worked.

It’s complex because there’s no clear answer. For most of us we can duck that harsh choice – except that we can’t. We can’t truly because it really does face us, and what’s causing the trouble is that we’re making choices and we’re not sure they’re the right ones. That’s exactly what those passengers faced – they had to make a choice about what to do and face the consequences, and they had to make the choice in minutes. That’s why I think this film will speak to us. It will allow us to get not to the simplicity of a conspiracy theory, but to the complexity of the real challenges we face.

Q: Those forty passengers have left behind family and loved ones who will be paying a lot of attention to this. Have you been in touch with them?

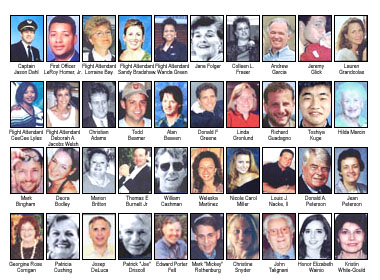

Greengrass: We spent an enormous amount of time – you couldn’t make this film if you didn’t have the full support. I believe it would not be right to make this film if you didn’t have the support of these families, and that’s the first thing we had to achieve. We’ve been to see every single one of those families. Every single one of them. We’ve been to see them personally, and sat with them, and we’ve had group meetings as well. We are moving together as a group. I have sat and I have explained my vision for this film, and we have the support of those families. All of them.

Q: Were any of them hesitant?

Greengrass: In truth, no. I think there were a lot of them that wanted to know my vision for it and what was important to me. But no, we’ve been greeted with extraordinary support. It’s my job to not let those people down. To tell the truth as I see it.

Q: The other part of that equation is the story of the hijackers themselves. How are you approaching their aspect of the story?

Greengrass: It’s a very important part of the story, and you have to tell it truthfully. Try and understand what they looked like, what they felt like, what they did. One of the things they did was to behave in an extraordinarily violent and blindly cruel way. That’s part of the story, too. You’ve got to understand what happened that day. And all those families feel that very, very strongly.

For the rest of us the temptation is to move on beyond 9/11. But those families, like the people on the airplane, know the situation that really faces us, and really know it. It’s a challenge as to what we do in the face of that threat of violence that’s facing us. We’re not going to be able to make an effort to understand what we do until we understand what we’re facing. What we’re facing, and why they’re doing what they’re doing. So we have to look very carefully.

Next time I’ll tell you about being there for the last day of filming, as Greengrass and crew shot the passengers, crew and hijackers arriving at Newark that day. Look for it soon.