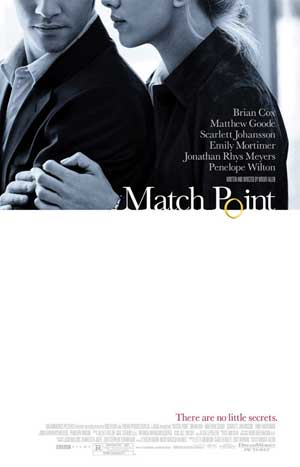

You’ve been hearing about the new Woody Allen film forever – it was the darling of Cannes. Now Match Point is finally getting a release and you can make up your mind whether or not it’s the glorious return that everybody’s been trumpeting.

You’ve been hearing about the new Woody Allen film forever – it was the darling of Cannes. Now Match Point is finally getting a release and you can make up your mind whether or not it’s the glorious return that everybody’s been trumpeting.

I recently had a chance to sit down with the stars of the film – Jonathan (Brian Slade in Velvet Goldmine!) Rhys-Meyers and Scarlett Johansson – and to talk about the movie and the weird relationships actors have with Woody. Rhys-Meyers plays Chris, an ex-tennis pro who marries above his social class into a moneyed family. Johansson is Nola, an American actress who is engaged to Chris’ brother-in-law. The two fall in love, and things get bad from there, leading inexorably to a shocking murder.

Be warned in advance – Rhys-Meyers was unable to talk about this film without spoiling it. I don’t think this is a movie that can actually be spoiled, but if you’re phobic about such things, watch your step.

Q: When you get the call from Woody Allen, what’s the first reaction?

Johansson: I was in LA and was planning on taking the summer off, and I got a call saying that the actress who was supposed to play the part dropped out; she had some personal reasons that she couldn’t do it. I got the script with a very nice note from Woody, which basically said, ‘If you respond to the movie I’d love to have you on, if not hopefully we’ll work together someday.’ I kind of just read the script for fun – I didn’t need any convincing. A week later we were shooting. It was pretty quick.

Q: Woody is press shy, but he has gone out of his way to say what a great actress you are, Scarlett.

Johansson: It’s a very sweet thing for him to say. I adore Woody. I would work for him forever and be completely satisfied, so it’s nice that he feels that way about me. Although he probably just said it because we were going to work together again! He’s such a pleasure to work for, and very funny and I adore him.

Q: I’ve interviewed a couple of people who have worked with Woody over the years and they all say that Woody doesn’t really hang out with – or even talk to – the cast. Does filming in a foreign country change his way of working?

Rhys-Meyers: I kind of like that. I don’t have to become friends with somebody to work with them. I think it puts extra pressure when you have to placate each other. He’s not somebody who gives compliments, but if you’re still on set shooting the film, that’s compliment enough.

I remember one day doing four incredibly difficult scenes and the only thing Woody said to me all day was, ‘Good morning.’ I like that, because he’s basically trusting me to know what I’m doing. And I’m trusting him, of course, because he’s a proven genius as a director. That’s a very, very comfortable situation for any actor to be in because it allows you to open yourself up moralistically and creatively. That’s very, very good.

I don’t like back slapping. I don’t like ego massaging. Where as it feels good at the time that your ego is being massaged, as soon as your ego is not being massaged you feel less than. I think it puts actors and everybody else in a situation of inadequacy when it’s not necessary. I think the very democratic way in which Woody makes his production behooves the production. It makes people feel that they’re all in it together. There’s a certain hierarchy in films and we’d all be silly not to recognize it – there’s a pyramid system that actors and producers and directors are on the top of this pyramid and everybody else is beneath. On a Woody Allen film that doesn’t exist; it isn’t a pyramid, I think it’s a circle. Everybody within that circle has an equal part to play in the production of that movie. And no part is bigger than any other. That’s a very, very good way to work. I think that’s what makes Woody a successful director at 70 years old – and still piping out great films. You have to have a method and a system that works.

Q: How about you, Scarlett? You’ve done two with him, and I saw in Vanity Fair that you have nicknames for him like The Woodman, so I assume your relationship might be different.  Johansson: Like I said, I adore Woody. We have a lot to talk about. I would even describe him to be a bit of a chatterbox, really. The nice thing about Woody is that he’s shy – he’s painfully shy when you first meet him – but I guess that when you harass him enough then he eventually has to say something. I just kept on harassing him, and he would start to acknowledge that I was there. I would poke him a bit and he would speak. I guess we have that kind of relationship, we have a very playful relationship.

Johansson: Like I said, I adore Woody. We have a lot to talk about. I would even describe him to be a bit of a chatterbox, really. The nice thing about Woody is that he’s shy – he’s painfully shy when you first meet him – but I guess that when you harass him enough then he eventually has to say something. I just kept on harassing him, and he would start to acknowledge that I was there. I would poke him a bit and he would speak. I guess we have that kind of relationship, we have a very playful relationship.

I think Woody would never want to be thought of as cold or unavailable; he’s always on set, he’s always around when there’s equipment being moved or changing of the scene. He’s always available and very present, it’s not like he retreats into a trailer. He’s usually sitting in a chair somewhere going over script changes and eating some soup. I found him to be really available to chit chat with and talk to. I think his legacy is what makes him really intimidating, but Woody as an actual person is very warm and sweet.

Q: The film is bleak. In most films the bad character would get punished – here he gets away with it. [Spoiler in the answer!]

Rhys-Meyers: Sure. I think that’s the way of the world. Bad people usually get away with it. They get away with it on a small scale, like a murder, or cheating on their wives or cheating on their taxes. And they get away with it on a grand scale – international crimes. Who really pays for what people do? Very, very rarely they do. There are a lot of scapegoats. You have your greatest mystery – who killed JFK? Nobody is known to really- do you really believe one person killed the president of the United States? I don’t believe that. It’s the way of the world that bad people get away with things. Not everybody is punished for what they do.

But of course it does lend itself to can you forgive yourself for what you’ve done? Can you really live with yourself, knowing that you’ve not only murdered an innocent woman, but you’ve also murdered your lover, who is pregnant with your child. That’s a very, very heavy anvil to carry around for the rest of your life. I think the last shot of the movie where you see Chris’ face looking out the window with his family and child behind him, is really, really, really, deeply unnerving. To know that he has to sleep every evening, and that when he closes his eyes his nightmares are gunshots. Woody did a very clever thing – he never showed Scarlett’s character lying on the floor with a hole in her. I shoot her with a shotgun from four feet away – do you know the hole that would put in a person? If Woody had shown that on the camera, if he had shown Scarlett lying on the ground with her belly open, then all sympathy would have been lost for Chris. Instead he showed the murder on Chris’ face and in Chris’ guilt. So therefore you kept the sympathy of the character.

Is it moralistically right? A lot of people would say no. But is it true to life? I think it probably is.

Q: Is Chris a bad person or is he doing a bad thing? Is a bad guy from the beginning, or is this something he’s forced into?

Rhys-Meyers: I never decided on that, but I think probably he’s not a bad guy. He’s a good guy who made bad choices, and saw that his only way out was to perform such a heinous crime. When people say this film is about luck, it is, but I see that in a different way. I see it as opportunity meeting preparation. You see Chris preparing himself for a better life. He’s studying Dostoyevsky, he’s making all the right maneuvers, he’s getting in with the family, he’s marrying the sister. Nola’s character is this great big time bomb dropped in his lap. How can you resist something so delicious? He can’t.

So what the film is in one way about is this is what happens when you don’t check yourself, when you don’t discipline yourself and give in to your carnal desires. Be careful what you ask for is what I’m saying, because you might get it. And he does. And when he gets everything he wants – the marriage to Chloe, the position as an executive and then he gets the bedtime with Nola, he gets too much of a good thing. And it doesn’t behoove you as a person to get too much of a good thing. There has to be balance, there has to be self-discipline.

Q: The dialogue has lots of American-isms. During the shoot did anyone dare to say to Woody, ‘Hey, British people wouldn’t say that.’

Rhys-Meyers: No, because I think the terms we used – you must remember that we in Ireland grew up watching American television. All your TV shows were our TV shows. It wasn’t alien to us to use American terms like guys – we use these in life. Americanisms have become internationalisms.

Ireland grew up watching American television. All your TV shows were our TV shows. It wasn’t alien to us to use American terms like guys – we use these in life. Americanisms have become internationalisms.

I was asked this by a young journalist from the Irish Times, and she said, ‘You’re playing Irish. Was it written Irish?’ No it wasn’t. I was Irish, so Woody said make him Irish, which is kind of an in-joke for me, because there’s never been an Irish tennis player. So every time I say I’m a pro tennis player, I have to have a little chuckle. But she said, ‘Why isn’t your accent so strong?’ Now, I made a particular choice not to have an Irish dialect because I want somebody who lives in Des Moines, or Illinois, to be able to understand me. If I came off like Intermission, with a really heavy Irish accent, that becomes a colloquialism. That becomes a character within itself. I didn’t want that to become a character. And I wanted him to be a social climber. You’ll find that at the beginning of the film he’s a little more Irish, and as he starts to climb into the family’s throne, I suppose, he starts taking on their accents, their mannerisms. He starts to embrace that and starts to morph himself into what he thinks he should be for these people. He’s quite sycophantical.

Q: Scarlett, for the phone conversations it must be difficult having an argument with an actor who’s not in front of you. How do you make it real?

Johansson: It’s difficult. I’ve struggled with that – I had a scene in Lost in Translation where I’m supposed to be talking to my sister on the phone. It took ages to shoot that because there’s nobody on the other end of the phone and my character is supposed to be hysterical and it’s hard. It’s hard. It helps to have a script supervisor who reads dialogue well. I guess you just suck it up and do it.

Q: Did you like the scenes where you’re by yourself? Is it intimate, one on one direction from Woody? Johansson: In this case, a dramatic film, and having Woody in the director’s position and not in the cast, he’s very hands off. If you do a scene and he likes it, then he’ll move on. He’s not going to push you in every direction. Which I can be with or without – somebody like Paul Weitz, I’ll give a performance and hit all the points I wanted to do and he’ll say, ‘Let’s try something else.’ And you do it eight or nine times. With Woody if he likes it the first time he’ll look at the dailies and either reshoot it or move on.

Johansson: In this case, a dramatic film, and having Woody in the director’s position and not in the cast, he’s very hands off. If you do a scene and he likes it, then he’ll move on. He’s not going to push you in every direction. Which I can be with or without – somebody like Paul Weitz, I’ll give a performance and hit all the points I wanted to do and he’ll say, ‘Let’s try something else.’ And you do it eight or nine times. With Woody if he likes it the first time he’ll look at the dailies and either reshoot it or move on.

It’s a very small crew of people, so it is intimate to shoot a scene like that alone. You only have a few people in the bedroom and Woody standing by the monitor – by the camera, rather. He doesn’t use a monitor. Yeah, it was nice. All in a day’s work.

Q: You worked with two legendary directors back to back – Woody Allen and Brian DePalma [in the upcoming Black Dahlia]. Can you compare the two?

Johansson: They’re both very hands off, actually. Their personalities are dissimilar. For one, Brian lives in California; Woody is allergic to California. Brian is very boisterous. He says very old-fashioned kinds of things, which are very exciting. Like, ‘Let’s give the actors some room!’ You feel transported.

Whereas Woody is not very vocal! Even his direction to the crew is sitting there as another member of the crew, somehow. I don’t think they have too many similarities, other than that they shoot ten or twelve hour days. Which is nice; I think from Brian and Woody’s perspective they look at it and say, I’m exhausted, I’m not going to be able to work after 12 hours and we’re not going to be able to get anything good anyway. as opposed to Michael Bay, who worked for 17 hours and onward, just to finish on time. That was definitely a positive similarity.

But I think in both cases either director hires their cast because they feel like they’re able. I remember Josh Hartnett came to him the first day on the set and said, ‘Look, you’re in all this movie, so I’m just going to stay out of your way for this production.’ [to Rhys-Meyers] I think Woody had the same take on it with you; I’m going to see you every day so I’ll lay off you.