The Film: Days of Wine and Roses (1962)

The Principals: Jack Lemmon, Lee Remick, Jack Klugman. Written by JP Miller. Directed by Blake Edwards.

The Premise: Joe Clay (Lemmon) is a PR man who just found himself at a new firm where his penchant and prowess for partying and socializing makes him ideal for showing clients a good time. This does not impress his boss’s goody-good receptionist, Kirsten (Remick). But Joe eventually wins her over, gets her on a date, and even gets her to try alcohol for the first time. And it proves love at first sight for Joe and Kirsten, as well as Kirsten and booze. We jump forward in time. Joe and Kirsten are married, they have a little girl, and drinking is becoming an increasing problem both in their relationship and Joe’s career. The couple are circling the drain, so Joe, desperate to save his career, dabbles with AA under the guidance of his sponsor, Jim (Jack Klugman). Kirsten thinks AA is ridiculous and won’t go sober, and the roller coaster ride of Joe’s addiction continues.

Is It Good: Days of Wine and Roses‘ problem isn’t that it is bad – because it isn’t – so much as it is incredibly dated and functionally passé in 2011. Alcoholism certainly wasn’t a new subject for cinema in 1962, or even main stream cinema — Billy Wilder had led Ray Milland and himself to Oscar gold for the seminal demons of alcohol tale, The Lost Weekend, in 1945. What was a bit more novel here was Alcoholics Anonymous. Though the organization had been expanding for a couple decades, it wasn’t something people talked a lot about. This was 1962 after all; Mad Men era; the three-martini lunch was still in full swing. People had seen the drunk-cleaning-himself-up story, but they hadn’t seen much of a drunk-cleaning-himself-up with AA. Well, that’s not entirely true. The film is based on JP Miller’s own teleplay for a Playhouse 90 episode, which was directed by John Frankenheimer and starred Cliff Robertson and Piper Laurie, and which many people (including Miller) felt was superior to Edwards’ films. Laurie is a significantly more interesting and skilled actress than Remick, so that seems fairly logical to me.

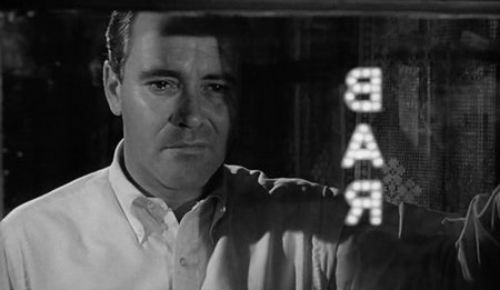

The early portions of the film are quite fun, particularly Joe’s awkward courting of Kirsten, and a weird scene where Joe foolishly sprays roach killer into the vents of Kirsten’s apartment complex. It is Jack Lemmon doing his Jack Lemmon thing, and this is prime The Apartment-era Lemmon too. That guy was on fire even when he was in crap. Of course it is going to be good. But once we enter the darker side of drinking, things start losing their bite. It is always a problem for older influential films that modern audiences are coming to them having already ingested the newer films they inspired or were ripped-off by. Watching The Lost Weekend it is hard not to smile during the film’s most iconic moment – an optical effect shot of Ray Milland walking in place, facing the camera, as neon bar signs fade past him, cleverly giving us a barhopping montage without the montage – without thinking of all the cartoons and comedies that have used the same image. Just as it is hard to watch an older film that used to be edgy, but simply isn’t by today’s standards. But these are slightly different issues than the one that hurts Wine and Roses. The biggest hurdle for a film like Wine and Roses is that it didn’t need to be clever when it was released, because there wasn’t much to compare it with. So watching the film now, even when adjusting for period context, aspects of it just seem obvious and bland.

Wine and Roses isn’t necessarily hurt because “I’ve seen these kinds of scenes before” so much as this film’s versions of now cliche “drunk scenes” aren’t as good as those you’ve seen in other films. But, again, we’re still dealing with Jack Lemmon, so there are definitely solid moments in here — like Joe embarrassingly getting demoted at work, or one of the film’s rare subtle scenes, in which Joe learns that Kirsten burnt down their apartment while he’s on a business trip. This problem only becomes truly pronounced when we reach AA and Jack Klugman and the film starts to feel like a paid advertisement for the organization or a public service announcement. Some of the dialogue feels lifted from a pamphlet, and I’m sure some of it literally is. Plus, the film sends Joe and Kirsten to some almost ridiculous extremes (Joe is in the booby-hatch for a while), which kind of detract from the “this could happen to anyone” feeling you’d think a movie about AA would have — even someone who gets shitfaced every night will likely think, “Well, I’ve never destroyed an entire greenhouse or woken up in a straight jacket, I must be okay!” In the end I was left feeling as though I’d sat through a silly Lifetime Movie, which was strange because of the groovy early-60’s Edwards vibe the beginning of the film had — this was after Breakfast at Tiffany‘s and immediately before The Pink Panther; an odd tonal detour for Edwards.

Is It Worth A Look: Unless you watch a lot of older films, no. Cause there are so many better Edwards films and Lemmon films and even Lee Remick films you could watch. Better older films about drunks too — watch The Champ or something; that has boxing in it. Or The Hustler; that has Piper Laurie.

The film does have some classic Henry Mancini music, but you can check that out separately.

Random Anecdote: To make sure that the studio wouldn’t try and reshoot the film’s bleak ending * Jack Lemmon flew to Europe for a vacation immediately after the film wrapped and stayed there until he learned the film was locked.

.

* SPOILER: The film ends with Joe sober, living with his daughter, and Kirsten refusing to admit she has a problem. The still above is the final shot of the film, indicating that Joe will be haunted by the temptations of booze his whole life.