Justice League: Generation Lost #24 (DC Comics, $4.99)

By Graig Kent

I can’t imagine planning out a 24-issue bi-weekly maxi-series is an easy thing. That’s a lot of pages (529 in this series by my rough count) to try and fill with one continuous story in a quick amount of time, not to mention tailoring the story to fit in with the ever-fluid continuity of the DC Universe. Judd Winick was the man charged with the task (with assistance from Keith Giffen in the early stages) of executing the story that filled those pages, and the result is unfettered mediocrity.

Justice League: Generation Lost is, from the title forward, an ungainly thing (honestly, what is that title supposed to mean in relation to the story anyway?). It started with the rebirth of Maxwell Lord in “Brightest Day,” the non-event to which this series was tangentially affiliated. Max, having died a villain at the hands of Wonder Woman, has made the world forget he ever existed, giving him freedom to operate and machinate without anyone aware that he’s doing so… except a handful of heroes, most of whom are former teammates of his from the Justice League International days, and they inexplicably remember him (if it’s explained somewhere why they, out of everyone, remember him, I myself have forgotten). So begins a game of cat-and-mouse, as the rag-tag Justice League chase after Max Lord, frequently falling victim to his traps and schemes, often acting as accomplices in his grand designs.

The series gets distracted throughout with the almost-deaths of Fire, Blue Beetle and Rocket Red (hitting that well far too many times) only to recover quickly to continue with their tedious objective, squaring off with OMACs, Checkmate, OMACs, Creature Commandos, OMACs, the Metal Men and (speaking of dried up wells) did I mention OMACs. Booster Gold hesitantly takes the lead on the team, which includes an annoyingly whiny Ice (herself recently resurrected) getting upgraded powers alongside a retconned origin story of little impetus but to fill an issue of story it would seem. The series has a few shining moments, such as Captain Atom’s jumps through time (which honestly would have made for a better series overall if his jumping through time and space were all that happened), the revelation that the world has forgotten Wonder Woman (because of the events in her book) and she’s thus out of Max’s reach, the well-orchestrated Magog fight, and some juicy covers from Tony Harris and Cliff Chiang (and variant covers from Kevin Maguire), but what the entire thing builds to is a dull final-issue melee against an Amazo-OMAC robot, a showdown between Max and Booster that literally goes nowhere and the ultimate revilation that this entire exercise is just a prelude to a new Justice League International series. All the references of a dystopian future from earlier in the series were red herrings, and all the allusions to Max’s grand scheme are for naught… turns out he’s just another cartoony villain with revenge on his mind.

Fans of the Giffen-era Justice League will not find much to cheer for in this book. On the one hand, the characters have naturally grown or changed from who they were 20 years ago, but in Winick’s hands (and even with Giffen’s early involvement) they felt unfamiliar. That specific time period of Justice League stories was known for its comedy and its heart. It was about family, and there’s little, if any sense of any of that magic in Generation Lost. Winick doesn’t seem particularly invested in the characters of the series, and just as often seems to be at a loss with where to take them from issue to issue. Winick’s team, who come together in a clunky, haphazard manner, throughout feel more like a group of people brought together and staying together out of necessity, and keeping them together beyond the events of this book seems even more like a forced conceit.

In the end, this series feels rather aimless and pointless (especially considering the revelations of the final chapter). If DC wanted to start a Justice League International series, they could have just started a Justice League International series, without the pretense of requiring an unfocussed bi-weekly event comic (total value $73.76) to launch it.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Doom Patrol #22 (DC Comics, $2.99)

Doom Patrol #22 (DC Comics, $2.99) By Graig Kent

I’m not certain the latest Doom Patrol was anyone’s favorite book. I’m sure it had its fans (myself included), and I consider many of the characters in the series favourites of mine, but I just don’t think it was the kind of book that inspires fervent fanaticism. From the outset my primary interest was the Metal Men back-up feature that ran through its first seven issues, and I often had difficult sustaining interest when reading the info-heavy main feature.

Keith Giffen was the man behind the 22-issue run of the series and despite best intentions early on he did get mired in the convoluted continuity of the characters. The efforts he made to resolve the conflicts of the past were admirable and actually quite well done, but still many of the series issues (the best ones I might add) were side-tracks, devoted solely to clarifying the main characters historical progression, through their origins, deaths, rebirths and the many other twists that they’ve endured.

Outside of the character-specific stuff, he concocted a rather bizarre – still perhaps not bizarre enough – team roster including the original four (Robotman, Elasti-Girl, Negative Man, the Chief), former Teen Titan Bumblebee, Crazy Jane and Danny the Street (from Morrison’s run), and even Ambush Bug. Giffen twisted some classic villains on their head, created a few new ones, and assembled them all under a corporate masthead as adversary. The Doom Patrol settled in on Oolong Island, a island nation populated by mad scientists, so there was a built-in episodic premise (of the Doom Patrol fighting the mad scientists’ “mistakes”) that was never actually used, and the setting generally acted as the curious launching pad for some off-beat fake-politics stories.

This final issue finds Oolong Island the subject of a hostile takeover by the corporate coalition of the Doom Patrol’s enemies. The DP, having been previously evicted, still come to the island’s defense, mounting a offense that surely can’t succeed. How it all plays out is rather a stroke of metatextual genius on Giffen’s part, utilizing Ambush Bug in the only way in which Ambush Bug should be. Is it a cop out? Quite frankly, of every end to a Doom Patrol series (and I’ve seen a few) this is easily the most fitting for the book. Okay, maybe it’s not brilliance incarnate, but definitely clever and absolutely hilarious.

I doubt that the Doom Patrol will ever truly be a huge commercial success (even Morrison’s run wasn’t setting sales charts on fire at the time), and there’s really no way this series could have been, but had Giffen embraced that lunacy even a little more, and had the artists pushed themselves further into, say, more Ditko-esque territory, the series would have at least been more buzz-worthy. This isn’t to disparage the art on the book, as Ron Randall and Matt Clark did a very capable job as a tag team, providing exceptionally clean, well orchestrated panels, alas they never really pushed themselves to get out-there stylistically.

With a finish like this issue, I’m actually sad to see it go, but that said, come next month I’m not sure I’ll notice it’s gone.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Gladstone’s School for World Conquerors #1 (Image, $2.99)

By Adam Prosser

I’ve heard it argued that dialogue is one of the least important aspects of writing. This argument was being applied to movies and TV when I read it, but it may be even more appropriate for comics. For decades, with a handful of exceptions, comics had pretty crummy dialogue—Stan Lee and Chris Claremont were both canonized simply for raising the bar a little in this area—and yet it didn’t seem to make the stories that much less compelling. Heck, the Fourth World is one of the greatest comic series ever published, and its dialogue is legendarily awful. Even to this day, the number of comics being published with what I’d call elegant turns of phrase are few and far between. The fact that this stuff doesn’t have to be spoken aloud certainly helps.

That’s not to say that I don’t enjoy snappy patter in my comics, or groan a little when I see grammatical errors or thudding cliches in a supposedly professionally published book. But, as Gladstone’s School for World Conquerors #1 proves yet again, a solid premise and lively storytelling (and terrific art) can carry a book past clunky dialogue.

Obviously, the premise is right there in the title: this is a “kids go to school to learn to be genre characters” story, just like that ever-popular series about the boy wizard. I think it’s called “The Dresden Files”. No, wait: “The Illuminatus Trilogy”. Anyway, the first half of the book details the clever origins of the innocuously names Gladstone’s, a supervillain’s school on Mars founded by a hapless C-list sorceror but currently run by a Dr. Doom knockoff through an amusing series of circumstances. The second half of the book (it’s an expanded 40 pages, not bad for your $2.99) introduces the series’ main kid characters, from the “legacy” supervillain Kid Nefarious to the moon-eyed Mummy Girl to the bullying Skull Brothers. Writer Mark A. Smith does some smart things, including avoiding most of the more egregious high school clichés (though not all of them) and setting up Gladstone’s as a prestigious private academy full of hypercompetitive kids. This latter gets into one of the potential pitfalls of this “cool school” subgenre—kids usually hate school, but learning to be a wizard or a supervillain would be incredibly awesome, so it’s good to have a reason for the kids to want to succeed.

The book’s biggest success, though, is the artwork. Artist Armand Villavert and colorist Carlos Carrasco are very much of the Mike Mignola/Gabriel Ba school of hyperstylized design, expressive linework, and flat colors that let the shapes pop, conveying the action loud and clear. It’s a perfect style for a kid’s book.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

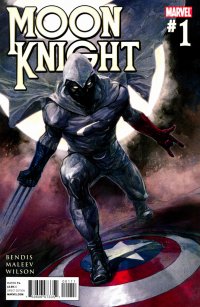

Moon Knight #1 (Marvel, $3.99)

Moon Knight #1 (Marvel, $3.99)

By Jeb D.

The last Moon Knight series got off to a respectable start, with noted crime novelist Charlie Huston finding a strong voice for the character, with nods to the larger Marvel U (“Hawkeye thought he was funny“), and plenty of hard-edged action for Marvel’s white clad Batman-by-way-of-The-Shadow (fun fact: according to Steve Englehart, it was The Shroud that was supposed to become Marvel’s Bat-surrogate). But it didn’t take long for the character’s ridiculously convoluted origin, or series of origins (one of the ways that Moon Knight has always resembled The Shadow even more than Batman), and contradictory backstory, to bog the series down into near-incomprehensibility. But one of the reasons that Marvel and Disney were a perfect partnership is the fact that neither company is willing to leave a character on the sidelines if they feel there’s an audience out there, so here’s Marc Spector, revived once more, this time in the hands of one of contermporary comics’ most successful partnerships, writer Brian Bendis, and artist Alex Maleev.

Of course, if you’re going to try a new Moon Knight series, it would be hard to imagine a more natural choice than the Bendis-Maleev team, since their definitive run on Daredevil (and, I would argue, their intriguing work on Spider-Woman) would seem the ideal model for a Moon Knight ongoing series. And there’s a lot of that here: pop culture awareness (we meet Marc Spector at the premiere of a new action-adventure TV series), Elmore Leonard-inspired dialogue (two thugs engage in an archly comic discussion over the future prospects of criminal employment in a world of super-powers), street-level take on a classic Marvel supervillain (in this case, Mr, Hyde), a hero who goes into action filled more with doubt than determination, a great fight scene, bits of half-forgotten Marvel U lore threaded into the storyline, and a great don’t-miss-next-issue ending. As I say, though, Huston also got off to a good start, so the fact that Bendis seems to have his finger on this character’s pulse may or may not mean that he can craft a coherent Moon Knight story (or even that he wants to), but I’d bet he’ll have less trouble than some of his predecessors at finding just those parts of the Marc Spector/Khonshu background that work, while simply ignoring the ones that don’t… which, at this point, is the only sane (so to speak) way to approach the character.

Maleev’s in his brisk, slightly sketchy mode here (rather than the meticulous photo-based work that characterized Daredevil), which keeps things nicely paced: it’s less immersive than his brilliant work on Scarlet, but appropriate for what will hopefully be a series that balances hard-hitting action with the murk of mystery. It’s also full of nicely subtle touches (he beautifully conveys the unconvincing nature of an actress’ performance in the “Gotcha-it’s-just-a-TV-show” opening).

A Moon Knight series has to be about more than Marc Spector’s fragile mental condition, but if you don’t address it at some point, you lose the depth that allows the character, at his best, to transcend his obvious influences. Which brings me to one more thing about the book, and it’s hard to talk about it in non-spoilery fashion, but here goes: the launch of the new Moon Knight series, as is often the case, is festooned with guest appearances by fan faves like Spider-Man, Wolverine, and Captain America; it seems they’ve decided that Los Angeles needs a resident costumed badass, and they’re asking Moon Knight to take that on. And Bendis’ approach to this form of spandexed product placement is either utter cheese or diabolical brilliance, I haven’t decided which.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

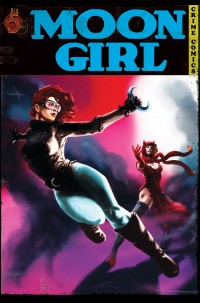

Moon Girl #1 of 5 (Red 5, $3.50)

By Jeb D.

The public-domain superheroes of the Golden Age have provided fodder for everything from Alan Moore’s America’s Best Comics universe to the cheesecake-fest of FemForce to the seemingly endless Alex Ross-guided Project Superpowers series. This is the first one I’ve seen pitched as “Mad Men meets The Dark Knight,” though: could even Stan Lee have come up with a desription so over the top? It’s such a preposterous analogy that the fact that the principal character is a woman seems like a minor detail. But even if it’s not quite as remarkable as that comparison might suggest, it’s still worth a look.

So, here we have Gardner Fox’s Moon Girl, fighting crime in the 1950’s. Expat Russian princess Clare Lune (maybe it’s just me, but if I were going for something edgy and hard-boiled, I might have changed that name) was a social revolutionary in the 1940’s, and had hoped to hang up the tights after having done her part to fight the good fight for truth and justice (American way, not so much), helping humanity in her daytime profession as a nurse. However, in the paranoid, red-baiting 1950’s, her legend has inspired a violent anti-establishment movement, that will test her commitment to her principles.

Series writers Tony Trov and and Johnny Zito are new to me (their credits include the Harvey-nominated “The Black Cherry Bombshells,”), and this is evidently the first print publication of their digital series. Troy and Zito have given this first issue a fractured, almost schizophrenic structure that seems to mirror the times and mental state of its heroine, fragmented, jumping back and forth, bringing in characters and concepts with little introduction. And one of the perils of reviewing comics like this, of course, is that it’s impossible to know if this storytelling approach will pay off down the road, or if it’s just mildly annoying (and, yes, it might turn out to be both). The opening fight with arch-nemesis Satana gives a few clues about Clare’s state of mind (and the fact that her super-self was once driven by something she fears will get out of control), but most of the exposition in the book is deliberately obscure; hopefully, though, future issues will pull together the disparate noir and sci-fi elements (oh, and the zombies- let’s not forget the zombies) and bring a bit more structure to the narrative.

Also new to me is artist The Rahzzah, whose painted work resembles nothing so much as a fever-dream mashup of Clayton Crain and Alex Ross, with the former’s ghoulish fluidity combined with the latter’s love of retro stylings. It’s certainly an amazing looking book, and the art is the principal reason I’d recommend it, though it’s another case where waiting for a collected edition might bring the added benefit of a stronger, more complete, story.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars