The Movie: A Knight’s Tale

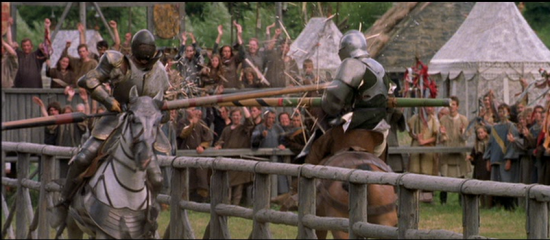

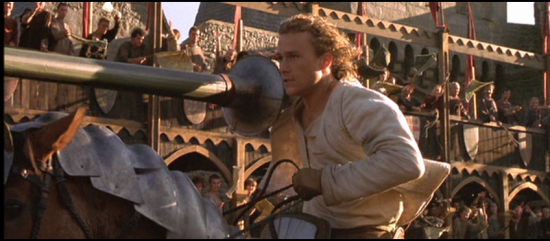

The Gist: Poor peasant William Thatcher (Heath Ledger) gets it in his head that he can pretend to be a noble, thus allowing him to compete in the jousting tournaments. He finds he’s pretty damn good at it, winning left and right, though he finds a nemesis in the powerful Count Adamar (Rufus Sewell). Along the way, he woos a lady of the court and helps Geoffery Chaucer (Paul Bettany) solve both his gambling habit and his issue of constantly losing his clothes, which oddly seem to be related. Oh, and also some fantastic jousting stunts and rock music and such.

The Moment: The opening of the film, actually. William and his two friends, Roland and Wat, discover that their master and employer, Sir Ector, has died during a break in the middle of a jousting tournement. Wat is despondent–he hasn’t eaten in three days, and was counting on Sir Ector’s victory to put some food in his stomach. Roland, the most sensible of the three, starts to leave to inform the officials. But then William gets a crazy idea–what if he rode in Sir Ector’s place?

Why It Matters: Let’s talk about tone for this one. Setting the tone is probably the most important thing you can do in the first ten minutes of your film–up until then it’s all presumptions and expectations. The audience doesn’t really know what you’re going to give them; there might be an idea of what you’re going to give them based on trailers and ad material, but essentially when the lights fade and the studio logo unfolds you have a blank slate. The audience is yours for the taking until those first few minutes start rolling, which as any stand up comic will tell you is when you have to hook them, or suffer the consequences.

For films that follow a simple A + B = C type of plotting, with instantly recognizable arcs and rote character beats, this doesn’t seem like such a big problem. It’s the McDonalds method of filmmaking–you know exactly what you’re getting before you even pull into the parking lot. There’s no surprise, and there doesn’t need to be.

Unless. Unless your film is different, isn’t content with simply serving up the same old hash, has something on its mind and, smiling, wants to share it with you. It doesn’t even have to be an issue movie, just a film where the makers want to subvert your expectations a bit. Then the hook becomes incredibly valuable, since without it you risk knocking your audience right out of caring about your movie. Hook’em, or lose them.

A Knight’s Tale does a lot of things right, in a lot of departments. It works as an old fashioned adventure/action yarn, a slightly silly comedy, and most miraculously of all, featuring some real, honest, earned character moments with a thrilling dramatic climax. Sure, the good guys are really good and the bad guy is really bad, but even he is afforded some level of still resembling a three-dimensional human being, albeit an incredibly selfish and pretentious asshole of one. What’s weird is that this is the kind of film, with its familiar plotting and silly idea of being half traditional, half rock and roll, should have been a disaster. This could have been unbearable and full of self-satisfied “cute” moments, where the film is just oh so pleased with how clever it is. Y’know, like a Baz Luhrmann film.

But because it does the legwork to actually draw the characters rather than merely sketch them, the film becomes more than a faceless, disposable piece of summer entertainment, but more than justifies its stake as a memorable adventure film. Oh, and the soundtrack is full of classic rock tunes and in at least three scenes the characters openly sing and dance along to them. Yeah, I know, right? There’s no winking at the camera or nudge nudge moments; it just happens, and in its own bizarre way, it makes sense. From the word go, the film tells you what it’s going to be and makes no apologies about it; you’re either on board or you can get out.

I give A Knight’s Tale a lot of credit, moreso than most other genre mashups from the 00’s, because in addition to the goofy and the what-the-hell of the rock soundtrack and anachronistic dialogue, it also puts in the legwork to make the story work on its own terms as well. We get all of this in the opening scene–a stated goal, the style of dialogue (the very staging of the scene feels lifted from a Shakespeare comedy, which is then peppered with Monty Python-esque quips), the chemistry between our trio of characters is established in a very classical tone. The story and writing of them film feels somewhere halfway between an 80s period flick like Ladyhawke and a Danny Kaye film (most notably The Court Jester.) The film sets it all up–adventure, action, comedy, and drama are in the hours ahead. A story anyone from 9 to 90 can enjoy.

And then we see peasants in a jousting arena start stomping and clapping to “We Will Rock You.” Wait, what?

It’s the mark of any well told tale to take time and make sure everything has a place, and that everything has a purpose. Comedic beats are illustrated and complimented with dramatic flourishes, and even though the hero’s journey isn’t technically breaking new ground, the ease and casualness with which the film unfolds feels like a blast of fresh, pleasing air every time I watch it.

The soundtrack is the film’s biggest hurdle (and in some ways its biggest success), but it more than justifies it in a number of ways: most of the music is popular in stadiums for sports, so why not take the biggest stadium based sport of the time and give it a modern context? It’s not just random songs, either, as they all serve purpose much as a traditional orchestral score would. More importantly, using classic rock the film avoids the pitfalls of using pop music in a movie. Commonly, if a song is just there because it’s popular at the time then five years after release the song won’t make any sense in the actual context of the film. As long as people listen to music, they’ll be listening to songs like “Golden Years” and “Taking Care of Business,” and so the songs don’t wear out their welcome.

That moment at the climax of the film–when our hero shouts his name right before he shoves his stick into Rufus Sewell’s face (…wait…) is a direct answer to the question posed at the beginning of the film, and William’s proposed solution to the problem it entails. He starts the film claiming that even a poor peasant can change his stars, and at first goes about it by creating a fake star. By the end of the film, though, he has changed his stars for real, and with every ounce of determination, shouts his name into history. And it WORKS. There’s no explaining the alchemy of a moment like that, it just DOES, and your eyes light up and your hair stands on end in the sheer thrill of experiencing an honest, no-shit movie moment like that.

Every feeling of rousing joy and cheering in that moment is earned, not through flash and shit thrown in because “it’s cool,” but through character work and good writing and acting. You put your focus on those three aspects and less on what fanboy demographic you can get to slobber, and you’ll have a film that can hold up 20 years after any “cool”isms will have faded, where it doesn’t matter in the slightest that your film opens with people in the 12th century stomping their feet to Queen instead of Mozart.