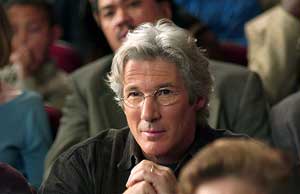

You can’t tell it from the transcript here, but Richard Gere bristled at the last question. I was surprised – Gere had been a very thoughtful interview, and then right at the end he seemed to get annoyed. I think the question’s a valid one, and I don’t feel sorry for having asked it (although I am sorry that Entertainment Weekly asked the "gerbil in the ass" question the week before, cutting me off before I could test my own courage with that one).

You can’t tell it from the transcript here, but Richard Gere bristled at the last question. I was surprised – Gere had been a very thoughtful interview, and then right at the end he seemed to get annoyed. I think the question’s a valid one, and I don’t feel sorry for having asked it (although I am sorry that Entertainment Weekly asked the "gerbil in the ass" question the week before, cutting me off before I could test my own courage with that one).

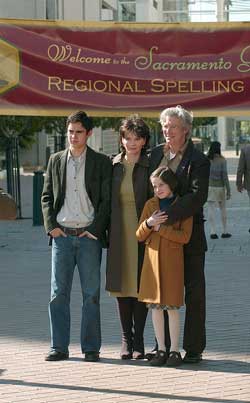

Gere’s new film is Bee Season, based on the best selling novel by Myla Goldberg. It’s a story of spelling bees and the Kabbalah – seriously – and about the slow dissolution of a family where each member is searching for meaning in their own way.

Gere plays a religious scholar – and a Jew, natch – whose daughter suddenly and inexplicably becomes an ace speller. He sees parallels with some of the mystical thought of the Kabbalah, and he begins to try to help her reach God, who possibly could also make her a math whiz.

Q: When you’re doing a film like this, which is so much about spirituality and faith and the belief in God, how important is your belief system when approaching the material?

Gere: In the film I play the violin. There’s no way I’m going to learn to play the violin in four months. I can learn to tap dance in four months, but I’m not going to learn the violin in four months. I’m not going to learn to be a teacher of Kabbalah in four months. This is really intense stuff. What I can do is find the keys that will plug into my own thirty years of training in Buddhism, and find things that are parallel, or resonant in the work that I have done. That comes into this work somehow.

There were enough parallels between the basic tenets of Kabbalah and the specific trainings of this guy, Abulafia, to Buddhism that I could fairly easily embrace the gestalt of it, without it being specifically about Kabbalah.

Q: What are those parallels between Kabbalah and Buddhism?

Gere: They would be articulated in a different way. In the movie we talk very much about Tikkun Alum – that the world has been fragmented and shattered, thrown into shards. Our job is to gather these shards together, to heal the world, put back together the broken pieces. Buddhism talk about Buddha nature – tathagatagarbha – it’s less about fragmenting than about ignorance. This basic Buddhahood, this Buddha nature that we have has been clouded over with ignorance. If you can remove the ignorance, then that Buddhahood or expansive quality of total openness, freedom, liberation, can be experienced.

They’re basically talking about the same thing but in different ways. One is about actively rebuilding, the other is kind of cleaning. They’re different ways of describing maybe the same thing.

Q: Is this the first time you’ve worked a directing team?

Q: Is this the first time you’ve worked a directing team?

Gere: Yeah, I didn’t know what that was going to be like. I had met these guys before the movie, and liked them a lot. But I didn’t know how it was going to work. Once we started rehearsing it was clear that basically David was running the set. Scott’s integral to the process but it’s not confusing because Scott doesn’t assert himself in the active, everyday running of the set.

Q: Somebody mentioned that you spoke to Michael Lerner –

Gere: I knew Michael Lerner before we made the movie.

Q: Did you guys talk any politics?

Gere: Sure. That’s how we started talking, about politics, not about spirit.

I just spoke to him a couple of days ago, I hadn’t heard from him in a long time. Michael’s a wonderfully controversial guy. He’s filled with extraordinary ideas, and he’s kind of fearless. It’s great to have someone like him. I wouldn’t want him to ever stop what he’s doing, because there’s value in what Michael does.

I wouldn’t call him political. It’s far too small. It’s like calling me political. Yeah, I’m interested in what politics does to us, and how it can help or hurt us as a society. As individuals. But Michael’s basic thesis that spirit matters, and how that can influence the way politicians think is, I think, really powerful. It continues to be, no matter what you think about Michael, they’re potent ideas. To use spirit in an expansive way, in a positive way, instead of a restrictive, minimizing way in the way the right wing lobby uses it, which minimizes us.

Q: When Juliette Binoche took a trip to South Africa for In My Country she said that the visit profoundly changed her. You travel a lot, and do a lot of humanitarian work. What’s been the trip that has most changed you?

Gere: There are so many. I don’t know where to begin. Obviously the Dalai Lama changed everything. But I’ve had many teachers, and many of them had nothing to do with spirit, or religion or anything like that. There was a guy named Charlie Clements – I saw a documentary about him, it actually won an Academy Award. This was maybe fifteen or twenty years ago. I went with him to Central America and we were in El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua. It was the first time I had directly seen what an insane US policy can do to people. He had been a doctor with the compasinos in El Salvador. He was right there in the middle of the worst of it in that dirty war. So to see the US government, to see that us as citizens, were supplying right wing despots with supports; we were supplying extreme right wing authoritarians with weapons… the killing and maiming and destroying the compasinos… that was the first time I was right in the middle of that. His sense of a very large vision – I would tell you his whole life, it’s a fascinating story, but you’ll never print all this stuff, so it’s pointless. But he had a huge impact on me.

huge impact on me.

Q: What was it about the script that enticed you?

Gere: It was beautifully written. Naomi Foner’s script was so beautiful and playable. Literate. I read the book and I could see where this was coming from. It’s a beautiful book. It may be brilliant. It may be a brilliant book.

It was everything it was dealing with. I thought it was an interesting ensemble of characters. All of them searching, in their own, bumbling way – as we all do – for God. I hadn’t seen that movie before.

Q: Actors talk a lot about chemistry, but here you had to have almost the opposite with Juliette Binoche. Is that hard to do?

Gere: That is hard. Juliette and I knew each other before. Not well, but we knew each other, and respected each other. We wanted to work together. In fact we were supposed to do a film together years ago but she got pregnant and we couldn’t do it.

Juliette’s approach to this character in this movie – and she apologized in advance for it – was to pretty much stay by herself. We didn’t have much of a dinner after the shooting kind of relationship. She was totally open in the process of making the movie, and totally open, generous and giving, but she made the decision to keep separate from me, as we were in the story. These two people just didn’t connect.

Q: Is Emperor Zehnder going to happen?

Gere: I don’t think it’s going to happen. At least not with me. It was too complex and expensive to shoot in Antartica. I went down there – we almost got stuck down there two months waiting for the weather. It costs minimum a thousand dollars a day to shoot. When you take everyone down there and make them wait for the weather so you have a day to shoot, you may have a window of three to four weeks where you could shoot. And in those three to four weeks you may never have the weather. You couldn’t even insure that movie.

Q: So March of the Penguins didn’t inspire you guys that if they could do it…?

Gere: We were going to use some of their out-footage. They were down there at the same time we were going to start to shoot.

Q: And you’re in Andrew Lau’s new movie.

Gere: We start that in two weeks. I’m kind of a social worker cop and my job is to monitor sex offenders. I have a route, like Willy Loman, and I travel it, checking in on them. He’s two weeks from retirement, but he has a sixth sense about these things – he knows when someone is going to spin out. He asks the file questions – how are you doing? – but he’s really looking in the eyes and listening to the voice and he just gets a sense.

Q: A couple of weeks ago George Clooney was doing press for Good Night, and Good  Luck, and he said that he doesn’t like to get involved in political stuff upfront as a spokesperson because it gets turned into Hollywood vs the Heartland. Is that ever something that concerns you, especially with your faith? Do you ever worry that the press is getting it as “The Dalai Lama, the guy who hangs out with the actor from Pretty Woman?” Are you ever concerned that focus becomes skewed from where you want it to be, whether it be the issue or your faith?

Luck, and he said that he doesn’t like to get involved in political stuff upfront as a spokesperson because it gets turned into Hollywood vs the Heartland. Is that ever something that concerns you, especially with your faith? Do you ever worry that the press is getting it as “The Dalai Lama, the guy who hangs out with the actor from Pretty Woman?” Are you ever concerned that focus becomes skewed from where you want it to be, whether it be the issue or your faith?

Gere: I’m not pushing anything.

Q: But when you do speak about any cause or issue, be it Tibet or your Buddhism.

Gere: What I’m careful about is only talking about things I have experience in. HIV/AIDS is something I’m considered an expert in, worldwide. Buddhism is something I’ve done for thirty years. The other things that I would talk about are things that I would consider I know enough about that I could speak about with enough authority.