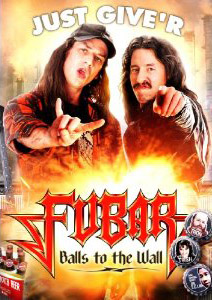

Not many outside of the Great White North and the indie film festival circuit had known about either of director Michael Dowse’s two independent features: Fubar, and it’s recently released sequel, Fubar: Balls to the Wall (read my review here). But now he’s becoming more of a known commodity with both the Canadian indie sequel – about two loser rocker dudes enjoying their first taste of success (as union laborers) – which premiered at SXSW to rave reviews just days apart from the release of his not-so-well-received Hollywood debut, Take Me Home Tonight. While the two films share a common release month and an affinity for aspects of that revered decade called The ’80s, that’s about where the similarities end.

Not many outside of the Great White North and the indie film festival circuit had known about either of director Michael Dowse’s two independent features: Fubar, and it’s recently released sequel, Fubar: Balls to the Wall (read my review here). But now he’s becoming more of a known commodity with both the Canadian indie sequel – about two loser rocker dudes enjoying their first taste of success (as union laborers) – which premiered at SXSW to rave reviews just days apart from the release of his not-so-well-received Hollywood debut, Take Me Home Tonight. While the two films share a common release month and an affinity for aspects of that revered decade called The ’80s, that’s about where the similarities end.

I had the chance to talk with Dowse – an amiable, Montreal Canadiens fan who lives up to the common perception that Canadians are extremely nice people – about the fun of shooting smaller, improvised movies, bouncing back from a troubled studio production, and what’s up next.

Ryan Mason: I admit: I had no idea Fubar: Balls to the Wall was a sequel. It worked great on its own – never felt that I was missing some previous explanation. Was that the idea going into it?

Michael Dowse: Yeah, we wanted to make it a standalone film with its own narrative and story, but keep those nods to the original for fans of Fubar. Basically just wanted to explore what these characters were doing later in life.

RM: You’re a co-writer on this film, along with stars Dave Lawrence and Paul J. Spence. Since a lot of it was improvised, what was the writing process like?

MD: For the first one [Fubar], we just wrote a three page bullet point document after we had shot most of it. We realized we needed to figure out where that thing was going. On the second one we had basically what looks like a professional treatment, a script that has no dialogue. Because we were working with a professional crew and we needed to do bigger stunts and set pieces, we needed that treatment. And then also for us, you can’t really improvise a film unless you know where the narrative is heading. So we were pretty strict about plotting out where the story goes. What’s fun about it is letting the actors go from A to B in their own way, but you can’t really direct it or make it without knowing where each scene has to go and where each scene fits in the narrative.

RM: So you knew how the whole film was going to play out beforehand.

MD: You kinda knew the point of each scene. What actually had to happen at the end of the scene – how they got there was sorta the fun part. It’s a fun way to work – improvising – you just need to know how to do it.

RM: Seemed like it must’ve been a blast.

MD: Absolutely, it was so much fun to make it. I had just done a 20 million dollar studio film before that so this was kind of a direct reaction to that where we’re making something smaller but trying to make it way funnier and tons of energy to it. Everything tha the first one was just on a bigger budget.

RM: You shot Take Me Home Tonight before Fubar: Balls to the Wall?

MD: Yeah, I shot Take Me Home Tonight in 2007 when it was called “Kids in America.” And I shot Fubar II in 2009 after two years of post [post-production] hell on “Kids in America”. Take Me Home Tonight isn’t my cut of the film. I wasn’t involved in that edit at all. I obviously shot it but I won’t venture anymore into those shark-infested waters. But it’s definitely not my cut. So I see this [Fubar II] as my reaction to Take Me Home Tonight where I’m just going back to my basics of just pure energy and just comedy and characters you like and having a great time with it.

RM: How was the editing process on this? On the Blu-ray there were a bunch of deleted scenes that were really funny and they went on for a while. How did you choose which elements to grab to make it in the final cut?

MD: When you don’t write any dialogue and you improvise everything, whatever time you’ve saved by not writing you pay three-fold in the edit suite. Our first cut was six hours long. And basically it’s a giant playoff system where you throw up all the jokes you think are remotely funny, try to find some backbone to hang them all off of in a scene, and then you put them all up and you go from a six-hour cut to two-and-a-half hour cut pretty quickly after that. You see the cream that rises to the top. But there’s no easy way of doing it except just to do it and wade through the footage and look at it all and pull the stuff you like and throw away the stuff you don’t like. But it’s a fun way to go. And it gets really fun when you get under the two-hour range because you really start to see the shape of, and the backbone of, the actual narrative. You then start to build things from there and also start to pull things from some of the stuff you’ve cut to fortify that narrative. It’s a really interesting process. It takes a while but it’s worth it; you get a really funny film.

RM: There are some elements of this being a mockumentary but it’s not nearly as big a part of it as in the first movie. Was that planned ahead of time or did you shoot it that way and those parts just didn’t make it into the cut?

MD: I felt that on the first one we did more of it and we pulled it out, you know, we spent a lot of time on motivating the camera and this filmmaker. What we found was that we just didn’t fucking need it at all. So on this one, we didn’t have a ton of it. We were kind of throwing away the rules of the mockumentary. We didn’t want to make a true fake documentary. We kinda just wanted the best of both worlds where we could have a shaky, this-is-gospel camera angles but not have to motivate it – nor did we feel like we needed to motivate it at all. Basically we just used the first person interviews essentially as narration to get through some tricky story points. But that’s all we’re using them as. Nor do I think we even need to motivate or justify why we’re shooting like that or anything like that. I think people just accept it. Especially now, I mean, it’s so been overused. To have that conceit that there’s a filmmaker in your film, at this point feels way overdone. I think everybody and their dog has seen that. I’ve done a fake documentary. I’ve done It’s All Gone, Pete Tong which I consider to be a fake biopic. And with this one we were just like, fuck it, who cares? They all understand what’s going on here. There’s a bit of a conscious effort to bridge between the first and second by using them, but we throw that away very quickly.

RM: Did you have a different approach to the sequel since you had more money to play with?

MD: We just wanted it to have the same sort of energy and basic DNA as the first one, but do bigger, crazier, stupider things with the production crew and the stunts. What was fun was writing the second one knowing that we’d have a bit of money and be able to put them on a pipeline, whereas in the first one we were basically using what we had. So, Dave’s friend’s parents owned a furniture factory so Terry worked in a furniture factory. On this one, though, we could go, oh, they get a pipeline job; great, let’s create a pipeline. Which is a fun way to work. What’s also fun is just shooting. I shoot one camera and the D.O.P Bobby [Shore] shoots the other camera and we just shoot everything with two cameras and let the action happen. So shooting stuff like the pipeline crews is fucking hilarious because half the pipeline crew don’t even know what they’re doing. You know? They’re not pipeliners. They don’t know where to go, people are making up their own hand signals. They had a very cursory knowledge of how to actually pipeline. I’m sure most pipeliners who see the film are just like, “That is just the slowest pipeline crew ever.”

RM: Out of your first three features, two revolve around hair-metal dudes, and the other is actually set in the 1980s. What keeps drawing you back to that era?

MD: I’m a kid of the ‘80s. I graduated high school in ’91 so I was in junior high and most of high school through the ‘80s. But I think the movies were just two separate things. Take Me Home Tonight, when we originally made it, was a huge affection for John Hughes’ films and those ‘80s films we all grew up watching. And with Fubar it was just another off-shoot of the ‘80s which was metal – the first concert I ever saw was AC/DC. I grew up in awe and fear of bangers so it was something I wanted to explore. But I don’t think there’s much more similarities between them than that, though.

RM: One thing I liked so much about Fubar II was how you were able to really balance the ludicrous funny situations with these moments where you really do feel for these characters.

MD: I’m just proud I pulled off a suicide pact scene in a Christmas movie. That’s my narrative triumph in this film. Really we want this film to be at the top of people’s wish list come Christmas season. You know, one of my favorite movies is [National Lampoon’s] Christmas Vacation so I was very excited to make a Christmas movie that people can, hopefully, watch every Christmas. That was sort of the endgame we were all going for.

RM: And you have Goon coming up next.

MD: Yeah, I’m just editing right now. We’re just about done we should be locking in about three weeks. I love, love Goon. I’m really proud of the film. Seann William Scott gives an amazing performance. It’s kind of my Raging Bull on Ice: this hyper-violent, hyper-funny sports film. It’s about hockey but I think it, sort of, transcends being just a hockey movie by far. It’s definitely a punch in the face. I’m surprised at how violent it is, actually, even though I made it. I’m like, “I guess I really do know how to shoot fight sequences.” You really feel every punch… I’m a hockey aficionado so it was even more of a pleasure for me to capture hockey properly on film.