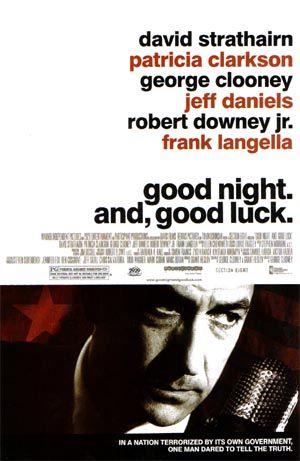

George Clooney’s Good Night, and Good Luck (I can’t seem to bring myself to punctuate it like the poster) is one of the year’s best films, and one of the great films in recent times. It’s a sober, factual and meticulous recreation of CBS News when anchor Edward R Murrow took on the Red-baiting Senator Joseph McCarthy. It was a pivotal moment in US history, one of the defining moments that showed what television journalism could be.

George Clooney’s Good Night, and Good Luck (I can’t seem to bring myself to punctuate it like the poster) is one of the year’s best films, and one of the great films in recent times. It’s a sober, factual and meticulous recreation of CBS News when anchor Edward R Murrow took on the Red-baiting Senator Joseph McCarthy. It was a pivotal moment in US history, one of the defining moments that showed what television journalism could be.

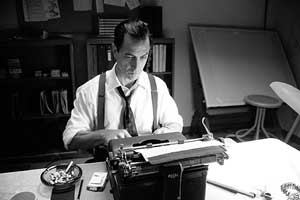

In the film, David Strathairn plays Murrow in a performance that’s going to top most critic and pundit Oscar lists. He may get ignored, though, since he doesn’t have any over the top histrionics or breakdowns – he just acts, and acts damn well.

Patricia Clarkson, meanwhile, plays the secret wife of Robert Downey Jr’s character – it’s a secret because CBS policy is that employees can’t be married.

They were part of a press conference a couple of weeks back, when the film opened the New York Film Festival. Also appearing were George Clooney and co-writer Grant Heslov. We’ll have them later in the week.

Q: Is there a responsibility in playing real people? Is it more than just what’s on the page?

Strathairn: Well there’s always more than what’s on the page. They’re two different beasts, so to speak, like when you have to pull something out of the imagination of the author and it’s a fictitious thing you’re responsible to a different set of circumstances, but always you’re responsible to the script. And in this particular case, it wasn’t a biopic; George wasn’t exploring a man in a bar and alone on his farm, so that to a certain extent focused what I had to be attentive to, but yes there is a responsibility when there is a historical character, especially of such magnitude as someone like Edward R Murrow that you are at least respectful of the memory people who know him and are still alive have of him. And in many ways there’s a responsibility to present as objective and respectful image to people who have no idea who he is.

Q: Without doing an impersonation.

Strathairn: No, this is not an impersonation. Because this is particularly an event around a  television moment, and that is where he became – his public presence was mushroomed out from the radio – there were images that were iconic and we have lots of archival footage to look at, and the broadcasts themselves, and the cinematographer Robert Ellsworth’s eye could compose that.

television moment, and that is where he became – his public presence was mushroomed out from the radio – there were images that were iconic and we have lots of archival footage to look at, and the broadcasts themselves, and the cinematographer Robert Ellsworth’s eye could compose that.

Clarkson: I was fortunate in many ways in that there’s no footage of Shirley, but I also was fortunate in that she’s still very much alive, and I met with her. I’m just madly in love with her! She’s a remarkable woman, still. She’s had a remarkable life; she’s funny and winning still at – I don’t want to give away her age! I met with Shirley, talked with her, I feel like I have a new friend in my life, extracted what I could. I didn’t have the density, like taking on Murrow. I wanted to be a part of this movie; there’s not a lot of Shirley, but what was there was choice, and I wanted to try to capture her spirit, her essence, her wit and intelligence (which she has mountains of). So it was lovely, kind of a beautiful thing that happened on this film for me, meeting this wonderful woman and extracting a little part of her and taking it into the film with me.

Strathairn: Patty also has to represent all of the women in the world in 1953! Which they will be thankful it was her.

Q: Has she seen it?

Clarkson: Shirley? Oh, she’s seen it four times [laughs]. She was there last night, she loved it. You have to understand, it’s very moving, all the people who lived it, this is their lives; it’s a very moving experience for all of them, we’ve witnessed it. And Joe was there- they were all there from our very first read through. We had one of the most extraordinary nights of my life last night; we had a dinner hosted by Walter Cronkite with all of these journalists, Brian Williamson. I sat next to Dan Rather all night, can you imagine? He’s Texan, I’m a Louisiana girl, I was like, ‘Look. I know about you Texan boys, OK?’ That’s why I was talking to Dan Rather!

Q: Did Walter ask if you were going to make a movie about him next?

Clarkson: He didn’t. He was very funny though.

Strathairn: It was in his honor but he somehow had been touted as the host of the evening, so he got up and said, ‘It’s an honor to be here as your host but I want you to know I’m not paying for this.’

Q: This is a very rigorous seeming movie. Was there a special rehearsal process?

Strathairn: The actual making of it, day to day, was a delight, just to put it mildly.

Clarkson: George knows how to-

Strathairn: He knows how throw a party. There’s a particular requisite of directing a film, and he knows how to do it.

Clarkson: It’s really a remarkable circumstance; from the moment you walk in, it’s alive.

Strathairn: You feel like there’s a safety net for you, which actors need, especially when they’re…

Clarkson: He creates this amazing, creative environment, and you walk in and everyone is treated with respect.

treated with respect.

Strathairn: They’re treated, from A to Z, as though they’re a part of the team. And no one’s safe from any jokes.

Clarkson: No! Never! You have to come prepared-

Strathairn: – to have a pie in your face.

Clarkson: But it’s also very serious. I want to put it in.

Q: Did George pull any pranks?

Strathairn: I wasn’t privy to any. Casting me was a practical joke, I think.

Clarkson: The boys in the newsroom had some stuff going on.

Strathairn: The boys in the newsroom had a lot going on. But no one person was the brunt of everything.

Q: David, what was the most difficult scene for you?

Strathairn: A couple of the broadcasts were pretty scary because of the tight, finite relationship with the camera. The movement was so constrained. And the words were so important, and the cadence and his focus were so iconographical…I was scared about those. At the same time they were very difficult but it was also- like I said, George gives you a sense of trust and allowance and support that you have a feeling he’s getting what he wants.

There’s a freedom there but also keeping Murrow in focus.

Q: Do you think Murrow felt like he was a success?

Strathairn: No, absolutely not. He was a very humble man who shied away from the limelight, even though if he embraced it in a fashion – like in London [during World War II] – he was very aware of the camera.

Clarkson: Kind of like you, David.

Strathairn: Yeah, well if I could have tea with Winston Churchill… I think he was propelled by an inate-ness throughout this, he wasn’t saying I’m going to make a hero out of myself, or I’m going to go after these people. It took him a long time to get into the game. He was very reticent to go out after McCarthy.

Q: Does he think he failed?

Strathairn: Great question, great question because after almost every broadcast he was sweating, he was very nervous. And I think he felt that he – he had an abiding hope that he was doing the right thing- but I think he never was quite sure if he got it right.

Q: Are the themes of this movie relevant today?

Q: Are the themes of this movie relevant today?

Clarkson: I think it’s very relevant. I think the themes of this movie continue on in our world, in our government, in our political system.

Q: Themes of what?

Strathairn: Responsibility of journalism.

Clarkson: Journalism, civil rights, civil liberties. Many things that Murrow…I think in a way you have to present the past so you don’t repeat it. And remember it.

Q: Is the movie an indictment of the Patriot Act?

Strathairn: Maybe it’s no coincidence that the film is being released the same week it is being voted upon. If it is a platform for potential neurosurgery to be applied on that, then yeah. But George and Grant will adamantly say this was not intended as a proselytizing, polarizing picture.

Clarkson: I think it truly began out of George’s love for Murrow.

Strathairn: And his father was the way he got into it. But there’s a number of relevancies that can be applied to the film.

Q: I saw this film the week Katrina hit, and I was impressed to see reporters on TV actually asking hard-hitting questions about race and society that they had avoided for a decade. Is it possible that a Murrow could happen now?

Clarkson: I think there are shades of Murrow in several journalists now. I think there are some great journalists who are rigorous and determined and thoughtful. I think it’s interesting with Katrina, something happened and everyone started to really step up to the plate.

Strathairn: It always seems that we are Monday morning quarterbacks in this society. Shoulda, coulda, woulda, if. Looking over our shoulder and fixing what happened yesterday and finding a way to do it, like they’re doing in Texas right now [this interview happened just before Hurricane Rita hit]. But I don’t think it’s possible for a Murrow to exist purely for the reason that he spoke to 40-60 million people at a time. Brian Williams last night said ‘I speak to 2-3 million at a given moment.’ It’s so fractured, and so diverse. The last high watermark is Walter Cronkite in 1968 when he came back and basically changed government policy by what he said about Vietnam. And Brian Williams said if I wanted to say, ‘”Have you no decency, at long last have you no decency,” I’d have to say it on a blog, I’d have to say it on C-Span, I’d have to say it on ESPN-‘

Clarkson: I’d have to say it on HBO-

Strathairn: For people to hear it.

Q: Are you worried that this film will only be preaching to the converted?

Clarkson: Well, if everyone who’s converted goes to see it that’s still a good thing. We don’t want to push away the converted. But I have to tell you, maybe I’m naïve, but I have this thought that- I have many nieces and nephews, and I have this feeling that 18-25 year olds, maybe off the college campuses where it’s going to play, Murrow might become their new kind of folk hero, And I don’t think that’s that far fetched. I think he might have a resurgence.

Strathairn: The political air of this film, which is an air that everyone breathes, it’s not just the choir, I think it’s in the air what’s in this movie. And since it’s black and white that in a way, for cinephiles, is a great thing. The cinematography in this film is extraordinary.

way, for cinephiles, is a great thing. The cinematography in this film is extraordinary.

And not only that, it’s an action picture. [laughs]

Clarkson: And there’s a lot of T&A too!

Strathairn: Thank you very much, Patty.

Q: There was a lot of smoking in the film.

Strathairn: You have to, because that’s what they did.

Q: I have heard you talk about improv in this film. How much was improv, and how much was the script?

Clarkson: The majority of what’s on the screen is what’s written. It’s such a beautiful script. You know, Grant and George did a masterful job in my opinion, but there were often kind of improvs at the top of the scene or at the tail end of the scene that got us in the scene, they kept a piece of it that’s in the film. But most of the large scenes that are in the film are written. But there was a lot of improvisation, especially all the boys in the newsroom. They would show up, Tom McCarthy, that whole crowd, they would show up and improv a lot.

Q: It must be funny for you to work with Tom in this movie after he directed you in The Station Agent.

Clarkson: I know, I know! Tom is so funny. Tom McCarthy’s in the film and he wrote and directed The Station Agent. I love Tom, he’s a remarkable writer/director, and he’s also an actor. He’s a consummate actor, so when he was on the set we had a very different relationship and it was nice.

Strathairn: We were given copies of the Times from March 1953. So we had the headlines of what was happening that day, or the day before. And George would say, ‘OK, Matt you’re going to cover local news; Robert Downey, you’re going to do the obits. Come up with a story about today and pitch your story in the scene. So boom, off we go. And you try to find something that is not directly related to the scene that day, but something that’s germane to the issues. So everyone was out looking. We got our hair and makeup done and everyone’s writing and memorizing lines, and George would come in and say, ‘What you got?’ ‘Well see…the Brooklyn Dodgers…Jackie Robinson…’ So it was alive, it was really alive. And it was really a testament to the ensemble; these guys were amazing.

Clarkson: They were amazing. And a lot of it’s on the cutting room floor. They would riff on the day, the events of the day.

Strathairn: Which was a tall order, because they talked differently back then, so you couldn’t say, ‘It’s like, well you know, um, well like.’

Q: I never knew that Murrow had that kind of wry sense of humor.

Strathairn: George gave me all the funny lines. I mean, he didn’t give me any funny lines, but he told me ‘If you do this, you’re gonna get a laugh.’ I wasn’t aware of, in this particular moment of Murrow’s life, a sense of humor. Maybe a sense of irony. And the other side of the coin, kind of a qualification- he was quick, he was witty, people said when he had one or a hundred Scotches in him he was a carry-on.

coin, kind of a qualification- he was quick, he was witty, people said when he had one or a hundred Scotches in him he was a carry-on.

Q: On Six Feet Under most of your scenes are with an ensemble cast of women, and here it’s you and an ensemble cast of men.

Clarkson: Yes. Which I’ve done on a few occasions on a movie.

Q: What’s the difference, acting in those two situations?

Clarkson: Testosterone. And estrogen. [Laughs]. I loved doing Six Feet Under, and working with Frannie Conroy, Kathy Bates. It was a dream, and one that I think I miss already. It’s difficult for me to articulate, it’s just a different feeling. They’re both lively.

Strathairn: Working with all men she walks into a room and they all look at her. Walking into a room when acting with a bunch of women they just look at her clothes.

Clarkson: All you boys, when I would walk into a room with those 50s dresses with the tiny waists –

Strathairn: Hubba hubba hubba!

Clarkson: When I would walk in in that red dress and all the boys would be like, ‘Ooooh’ I wouldn’t want to go home. So yes, it is different, but they’re both rewarding, but of course there is a marked difference.

Q: Were you one of the boys in this?

Clarkson: In a sense yes, but still you know… it was… I mean I’m not, but I was.

Strathairn: Keep digging.

Clarkson: It was sexy. It was very sexy. It was sexy and flattering. Let’s just get down to it, come on! I’m in a room with all these intelligent men, in a 23 inch waist dress with my hair all dingy doingy…

Q: David, are you going back to that other HBO series, The Sopranos?

Strathairn: I don’t think so, no.

Q: Have you ever wondered how you would react if you had to sign a loyalty oath, like in the film?

Strathairn: That’s a great question, because how many journalists are there out there now who want to say something – about the White House press room, let’s say. I mean, how many journalists are between a rock and a hard place, now? Those people have been embedded somewhere and can’t get their stuff out. What is most insidious today is you can’t go, ‘Oh, it’s Joseph R. McCarthy.’ You point a finger to what? And who? The fear that is in the room today is not as specific as it was then. You could be compromised in so many other ways than losing your job or going to jail. You may not even know you’re being compromised, so it’s really scary.

So this film can encourage and give hopes to those people who are in jail, and those who are about ready to die for this stuff. And it’s up to each person, when you come to that line in the sand, what are you going to do.