In the modern world the word genius is tossed around casually, but there are few actual geniuses out there. It seems like there are bursts of brilliance, but almost never the sustained light of a true genius.

In the modern world the word genius is tossed around casually, but there are few actual geniuses out there. It seems like there are bursts of brilliance, but almost never the sustained light of a true genius.

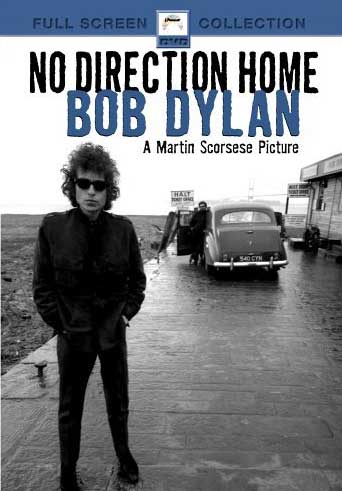

So No Direction Home is a double gift, in that it’s from a cinematic genius and it’s about a poetic genius. Martin Scorsese’s long documentary begins airing on PBS’ American Masters tonight and continues tomorrow; it’s a great film that takes on a difficult subject, a man whose malleability makes him so interesting but also so hard to pin down.

The most notable thing about Scorsese’s film, besides the glorious footage he’s unearthed, is that it’s not a hagiography. I suppose it couldn’t be – No Direction Home covers some of the same time as DA Pennebaker’s seminal tour documentary Don’t Look Back, where the guy is just behaving like a complete asshole. Scorsese does manage to put that stuff in perspective, though – while not forgiving of Dylan for being a jerk, the film is understanding.

There’s a new Dylan every few years and the latest one has been remarkably lucid and comparatively open. Last year saw the release of Chronicles Vol 1, an autobiography in process, which jumped across different periods in Dylan’s life. The book is just flat out well-written, which shouldn’t be a surprise but is, since Dylan’s been known to use language to obfuscate the hell out of everything. I don’t know if it’s in the spirit of that book that Dylan sat down with Scorsese’s interviewer (it needs to be noted that the director himself did not do the interviews. This has led some to question the real authorship of the film. To me it feels like a Scorsese movie in many ways, but I suppose that’s an issue people will debate for some time to come), but the Dylan here isn’t cryptic or mumbling. He’s straightforward and willing to plumb back in his life. He’s willing to open up the puzzles and mysteries he built around himself – to an extent. I don’t think the guy’s capable of being all that open, so what we get here is probably the best we ever will get.

Do we deserve more? The film asks that question as it examines Dylan’s sudden appointment as a messiah figure for the civil rights movement and youth in general. Scorsese begins the story in Hibbings, Minnesota, where Bobby Zimmerman dreams of being a rock and roll star, and follows his gradual transformation into a folkie and acolyte of Woody Guthrie, the patron saint of American music. Dylan was always different from the other guys on the scene, though – he wanted to be famous. He wanted to be Elvis, he would later say.

There’s a lot of Dylan talking about his history, and it’s wonderfully complemented with the people who knew him, including one-time rival Dave Van Ronk (Dylan stole an arrangement of the old time song House of the Rising Sun from him; Eric Burdon and the Animals stole it from Dylan. Forty years later Van Ronk seems bemused at the situation; it’s not hard to imagine he felt a little more than “annoyed” at the time.

Other interviews go a long way from making this just a worshipful piece. Joan Baez is fascinating to watch, not just because she’s retained her heavenly voice, but because we can see her struggling, even now, with her feelings towards Dylan. Dylan was happy to be a protest singer (even if he rejected labels) until such time as he became The Protest Singer, and his denouncement of that and his turn away from any overt political relevance in his songs was – and seemingly still is – a disappointment to Baez. But she loved and loves him all the same.

It seems like the 80s and 90s helped humanize Dylan. The man is an iconic genius for sure (he reveals in the film that he was only writing music for two years when he came up with Like a Rolling Stone. Some of the greatest lyrics ever penned came from a guy who had only just started doing it!) but he spent two decades squandering his talents and his fanbase. If his pedestal hadn’t been knocked out from beneath him it’s likely that this documentary couldn’t have happened.

Scoresese’s always been a musical director – his cues are usually perfect. In No Direction Home he gets to show off his ear by often letting the music and Dylan’s performance speak for itself. You don’t need a lot of commentary (and there is no narration at all in the film) when you can just show us Dylan playing Mr. Tambourine Man at the ’64 Newport Folk Festival and have an onscreen title tell us that this was taking place at the Topical Song Workshop. No one needs to come in and explain how this was the beginning of a fuck you to his fans that would culminate in an electric performance the next year – it’s obvious. Hell, it’s obvious just from the smirk on Dylan’s face.

I grew up in a world that had the myth of Newport ’65, where Dylan was booed for going electric and where Pete Seeger was going to chop the electric cables with an axe, completely solidified. It’s just a part of the popular rock knowledge. So it’s amazing that the film could shed new light on the event for me, by contextualizing it. No Direction Home shows the performance not as an artist trying new things, but as a kid chafing at the box he had been placed in. I’m pretty sick of labeling non-punk rock things as punk rock, but honestly, this was a punk rock moment.

There’s a ton of great performance footage on display, and Dylan fanatics will be most excited to see the English shows where he was steadily booed during his electric set (he came out with backing musicians – the guys who would one day become The Band, whose farewell concert – featuring Dylan – Scorsese would capture in the classic Last Waltz. In Dylan’s defense he did an acoustic set up front, giving these jokers time to get lost if they didn’t like the rock stuff). The entire documentary is punctuated with footage from maybe the most famous Dylan show, footage that most people never saw. In the film an audience member shouts out “Judas!” and Dylan replies, “I don’t believe you.” He then turns to the band and says, “Play it fucking loud,” and they shred through Like a Rolling Stone.

What I loved best about the documentary, though, is how deftly it charts the changes in the man. While the film only really covers the first five or so years of the man’s career, that was also one of his most fertile periods. Scorsese manages to bring us along for every shift in the man’s chameleonic character while also keeping us fully immersed in the time. The film shows the changes in Dylan first as reactions to the times, and then changes in the times as reactions to Dylan.

Had No Direction Home gotten a minor release in theaters to qualify for an Oscar nod, I have no doubt it would have gotten one. Maybe Scorsese just didn’t want to win his Oscar for a documentary. At any rate, it’s a great film, and possibly the best, most engaging and most informative musical bio I have ever seen.

(Note: Roger Ebert brings up the lack of Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, a folk singer who can claim to have had considerable influence on young Dylan in the years chronicled. The real missing piece, though, is Robbie Robertson, the leader of The Band, who for some reason does not appear in this film at all.)