Ralph Fiennes is one of those actors – one of those actors whose name you don’t know how to pronounce. Well, you know how, because you’ve heard it said by now, but when you first read it I know you thought he was "Ralf."

Ralph Fiennes is one of those actors – one of those actors whose name you don’t know how to pronounce. Well, you know how, because you’ve heard it said by now, but when you first read it I know you thought he was "Ralf."

He’s also one of those actors who are so good at what they do that you know people will talk about them thirty or forty years from now. And when you interview someone like that, you should be nervous. Good thing Ralph handles that all himself. In person he comes across as just a little uncomfortable, maybe just a touch nervous. It’s endearing.

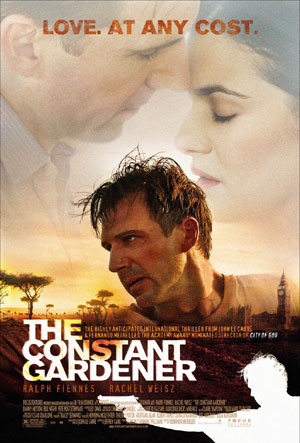

He’s starring in The Constant Gardener, the newest adaptation of one of spymaster John LeCarre’s novels. It’s directed by Fernando Mereilles, the genius behind City of God, and Fiennes’ co-star is the beautiful Rachel Weisz (not an easy to pronounce name in the bunch). The film opens this Wednesday, August 31st, easing us from the action season to the thinking season, as this is an international thriller with deep implications.

Q: Is The Constant Gardener as close as you’re going to get to a straight action film?

Fiennes: I was in Strange Days – that had some action in it.

Q: Can you talk about how your character’s gardening is important to the film?

Fiennes: I always liked the idea that gardeners are good at nurturing and have a degree of patience and a quality of patience, and they have to be persistent. Those are qualities Justin has. I haven’t asked John LeCarre directly why [he named the book The Constant Gardener] – but it seemed quite clear to me that given that Justin’s journey was from someone who was quite gentle and non-confrontational, and then something shifts in him and he gets quite stronger and more determined. I think that within him already there’s this  quality of patience and thoroughness.

quality of patience and thoroughness.

Q: And Tess is sort of the opposite.

Fiennes: I think the story works because of that relationship. You can say opposites, but I think they’re very, very different.

Q: This film has some amazing African imagery, just beautifully shot. Obviously you guys were on location to capture that – what was your African experience like?

Fiennes: I think it was a great achievement that we made the film there at all. Kenya doesn’t have much of an infrastructure for producing a film of this scale at all. Simon Channing-Williams, our producer and Fernando went to Kenya and they initially thought they would have to film it in South Africa, which has more experience with movies. But they very quickly realized they should film it in Kenya. Simon started working on setting up the film there. For us it was extraordinary, on many different levels. We shooting in locations that LeCarre wrote, they really exist. Not just Kibera, which is a talking point a lot now because it’s the biggest slum and all that, but also in the homes of the diplomatic community – all those homes, where Danny Huston’s character lives and our house, those are all well to do homes in Nairobi. And also at Lake Ticana, which is sort of a desert rock landscape where we filmed the ending.

That was extraordinary. There are four tribes living there for centuries, and they have been living on very little. They agreed, after some negotiation, to accept us. And we used them in the film. Simon, our producer, made sure that not only was the deal done with them an honorable one, but he has created a trust so that there is a long term interest in support for that community.

Q: How was the reaction of the Africans to you? There are a lot of happy faces in the film.

Fiennes: That’s one of the things that wrong-foots you, I think. When you go to areas with poverty of that level, you’re ready to feel shocked and some degree of shame, as a rich Westerner. But you’re wrong-footed because while you see these areas with no sanitization, no electricity, no running water, the spirit of the people – they’re enthusiasm, they have a sort of joy. The thing I carry away with me mostly is the sense of human contact. Whatever  the differences of culture, background, wealth, all those things, you have these moments. When you’re welcomed, you shake someone’s hand, you have a conversation and suddenly you’re all bound together because you share your own common humanity in one short moment. That’s the most moving thing I carried away.

the differences of culture, background, wealth, all those things, you have these moments. When you’re welcomed, you shake someone’s hand, you have a conversation and suddenly you’re all bound together because you share your own common humanity in one short moment. That’s the most moving thing I carried away.

Q: City of God is a great film, and so many people in the industry have noted it as one of their favorites. It must be great to work with Fernando.

Fiennes: Oh it was fantastic. Initially there was another directed attached , but he left the project, so for a short time we didn’t know who would direct it. Then Fernando came forward. I had seen City of God, and what we all thought would happen has happened, which is that Fernando has brought his own particular spin and take and energy to the story. Sometimes stories like this that are complicated thrillers, when they are adapted for the screen can become a bit plodding, and I think Fernando cleared out any dead wood in the screenplay. Not that there was a lot. And in terms of cinematography, there’s a great energy in the film.

Q: Does the fact that Fernando comes from a foreign filmmaking world affect his directorial style?

Fiennes: He’s not bound or used to a sort of style… In the studio system, certain things are expected of a film. People talk about first, second, third act, close-ups of actors – I think there’s a generic language for a lot of filmmaking that comes out of the commercial system. Not coming from that background he didn’t give a shit. There’s a freedom and a looseness and a flexibility in the way he shot that I hadn’t encountered before.

Q: Being Africa, seeing the continent, did that change your take on Justin?

Fiennes: No. I had a very good sense of Justin from the book.

There was a scene where… Unexpected things happen. It’s not about changing the character. I think my sense of him is very strong, and that was the reason I wanted to do the film, I loved the journey the man went on. But in the process of filming there are unexpected situations and one example would be that there is a scene where I go into a market place and ask people if they know a young boy. That wasn’t scripted – Fernando said, ‘There’s a market, I want you to walk through it and we’re going to have a camera  hidden in a building with a long lens.’ I didn’t know what kind of reaction I was going to get, I only knew a sentence or two in Swahili. I went up to these people and they didn’t know they were on film – they just responded, and I had to respond to them.

hidden in a building with a long lens.’ I didn’t know what kind of reaction I was going to get, I only knew a sentence or two in Swahili. I went up to these people and they didn’t know they were on film – they just responded, and I had to respond to them.

Fernando’s process is full of things like that. He just threw us into these situations. There’s a scene where I was driving down the road and these boys put stones in the road. That wasn’t rehearsed. ‘Go ask that mzungu – that white man – for more money.’ I had a few lines prepared to say, but I had a freshness. It was unrehearsed. They were different each time. They had been told to be aggressive when asking. It was that sort of thing that changed, that surprised me.

Q: Did you get a chance to visit any of Africa on your own while you were over there?

Fiennes: I had been before. I had been to Uganda and to Botswana. I wanted to get out on my own but I didn’t have much time, I mean I’m in a lot of the film. But I went out to the Masai Mara, which is the famous wildlife area. In fact I think they based a lot of the Lion King on the grasslands of the Masai Mara. Which I thought was beautiful but a lot of people were there.

What I did manage to do was do a food drop in the Sudan in a big Hercules. A lot of the southern Sudan is now probably too dependent on it – a lot of the villagers expect food now. The United Nations has a continual flow of food. But to go in an aircraft and sit in the fuselage and the door opens and the guys just cut the webbing that holds the food and it slowly falls out. You see these sacks of grain slowly fall out to this marked area. It was amazing.

Q: Does this film reflect your politics? How comfortable are you with that?

Fiennes: I have my thoughts about what’s going on. I don’t particularly feel comfortable about actors using whatever profile they may have to push their beliefs, unless they’re extremely well informed. But like any citizen of the world, I have some thoughts politically. I do. Certainly LeCarre’s anger about government collusion with big pharma, so there’s little transparency with the big pharmaceutical companies and how they sell their drugs, how they test their drugs, how accessible are their drugs to the poorer nations. That’s what this movie is pushing and I am behind that.

Q: Hard not to be.

Fiennes: Exactly!

Q: Were you aware of the way big pharma works before the movie?

Fiennes: The political thing for me was less of a reason to do the movie than it was a great part to play. I think actors are allured by – well, not always – but in this case I wanted to play Justin Quayle, and it was great that woven in and around the narrative the story asked some questions about corporate and government behaviour.

Q: What is it about a character that makes you decide to play him?

Fiennes: Instinct. I respond to a part just intuitively. It’s about how I feel about a script when I’ve read it, has it moved me. Who’s the director. Who am I going to act with. It’s just a feeling. I don’t think I plan a career, like I’ve done this and now I must do that. It doesn’t work for me. I just go with my gut.

Q: You had a lot of opportunity in this film to improvise. How was that for you?

Fiennes: I like to work that way, but it doesn’t happen often. I think on film it’s good because suddenly little energies and little moments can add a texture that’s very real and discovered and surprising to us as it happens to us. It doesn’t happen very often. It’s because time is expensive and here’s a script, and people have been doing all kinds of calculations about the length of a scene and the shooting time of a scene.

But Fernando works very fast and with great flexibility.

Q: Going back to how you choose your roles and your gut instinct, what was the gut instinct that made you choose Lord Voldemort in the new Harry Potter?

Fiennes: I wrestled with it actually for a bit. I didn’t know much about the world of Harry Potter before. After thinking about it, I just thought that this was such a full-on, meaty villain – a baddie. I have done more realistic villains, I suppose, but nothing in that  fantastical realm, that children’s realm. The Dark Lord – I haven’t really done that before. And I like Mike Newell. When I saw some pictures that they drew, ideas for the look, that was when I really took the bait, I think. It’s actually – I shouldn’t describe it! – it’s actually quite simple. I just thought, ‘Yeah, that looks really cool, I’ll do that!’

fantastical realm, that children’s realm. The Dark Lord – I haven’t really done that before. And I like Mike Newell. When I saw some pictures that they drew, ideas for the look, that was when I really took the bait, I think. It’s actually – I shouldn’t describe it! – it’s actually quite simple. I just thought, ‘Yeah, that looks really cool, I’ll do that!’

Q: Are you signed on for the rest of the series?

Fiennes: Not all. I think I’m doing the next one. I have a big fight with Dumbledore in the next one.

Q: David Cronenberg told me that he did A History of Violence partially because he liked the script but partially because Spider wasn’t successful at all. Do you think of doing work –

Fiennes: I think Spider was critically very successful. Sadly some films that are critically well-received don’t do well business-wise, and some films that do business don’t get reviewed very well.

Q: What’s more important to you – the critic or the audience?

Fiennes: I think I’d like to have both, ideally. You want a critical success and you want people to see it. It’s disappointing if something is well-reviewed and no one goes to see it.

Q: Do you want to work with Cronenberg again?

Fiennes: Yes. I love working with David. I had a great experience with him.

Q: You had worked with Rachel before.

Fiennes: We worked together on Sunshine, but we only had three or four scenes. We had a great time together on this – we sort of had to have. We both loved our roles. She loved Tessa and I loved playing Justin. Happily – and there’s no recipe for these things between two actors – we enjoyed interacting with each other. I think a lot had to do with Fernando encouraging us to be loose and to play and to improvise. There isn’t that many scenes we have together, but the film depends on the audience believing in this relationship, or wanting to know more about it. I think that because Fernando encouraged that playfulness between us, when I watched it there was something believable about us as a couple – tensions and jokes and teasing. That’s because we like working with each other. I know it sounds a bit bland to say I loved working with her, but it’s the truth. The energies between two people – you can’t prescribe how it’s going to work.

Q: Even though it was just your voice, how was it working on Wallace and Grommit?

Fiennes: That was fun. I didn’t know what to expect. It was quite hard work. It was quite a broad comedic vocal performance.

Q: Had you seen the previous shorts?

Fiennes: I hadn’t until I worked on this. Fantastic. There are some fantastic moments in this. They’re brilliant and their imagination is really quirky. It goes on and on – they’ll come up with one idea for a scene and it gets refined and refined until it’s almost surreal.