Gus Van Sant is a difficult filmmaker to pin down. Over the course of his career he’s made some of the boldest low budget films of our time and has also made one of the worst, most cynically commercial pieces of crap – Finding Forrester. Which is the real Van Sant?

Gus Van Sant is a difficult filmmaker to pin down. Over the course of his career he’s made some of the boldest low budget films of our time and has also made one of the worst, most cynically commercial pieces of crap – Finding Forrester. Which is the real Van Sant?

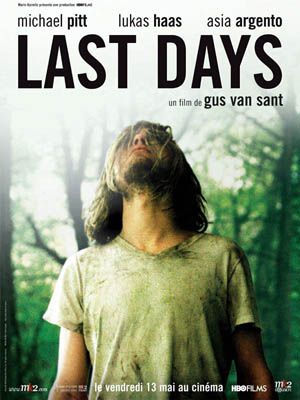

The answer, I think, is the indie director. I can’t help but believe that Psycho was not as straightforward as we were led to think, and Forrester, for better or worse, smells like a paycheck. Especially because after that film he began a triptych of incredibly obtuse and difficult pictures that has led to Last Days, an elliptical and strange examination of the three last days in the life of a guy who bears a really strong resemblance to Kurt Cobain.

I loved the film (read my review here), and was glad to have a chance to sit down with Van Sant. He’s soft spoken, and while we had been warned in advance that he would talk forever when asked a question, he definitley seemed succint.

Q: There was a piece in the New Republic earlier this year that talked about critics, especially Susan Sontag, being big supporters of Bella Tarr, and bemoaning the fact that generally American critics may champion foreign filmmakers but that the appreciation of foreign films was sinking in the culture. And that the critics who were championing them were becoming fewer. As someone who has been influenced by foreign filmmakers, do you think there has been a shift? Is part of the reasoning for you making a film like this to bring attention to –

Van Sant: No, this is really just me being impressed by somebody’s work that I thought had rethought their own – Bella’s earlier work in some way represented an influence that was a Cassavetes kind of thing, and really different than what he was doing later, which may have been influenced by Jansco. He was another Hungarian filmmaker who was using very, very long pieces. Somebody said that the reason he was doing that was some sort of union thing, where he could get money to rehearse but if the camera was rolling somehow that was an impediment to the money that came in. So he could actually spend a week rehearsing for free, and if he recorded it all in one take, he could do all this great work and it was cheaper. But I don’t know if that was actually true – and I’m talking about Jansco.

But in Bella’s work I thought I was looking at something that kind of predated our own film montage or film “wide, medium, close” that Griffith developed, montage that Eisenstein developed and that people like Hitchcock learned from that, and this whole thing kind of took shape that we still use today in almost everything we make. At least in our culture, Western culture. It seemed to go before that time and almost rethink cinema so that you’re looking at something that was an alternative thought to Eisenstein and Griffith and it was really beautiful. I was more taken with the style more than try to popularize European film or Hungarian filmmakers.

Q: Do you feel that lack of support for foreign filmmakers?

Van Sant: Susan Sontag was the hugest supporter of Bella, and she is like the best, if not the most, celebrated film writer. He had a huge champion. Too bad she died this year.

I think there is obviously this huge corporate machines making all kinds of movies whose intention is to make money. It’s sort of growing all over the globe so that these movies are occupying not only cinemas in the US, but in Italy when The Matrix comes out, all the screens are showing The Matrix. They’re not showing anything local. They’re not showing foreign films – I don’t know if they would anyway, ordinary Italian cinema. But there’s a sort of huge thing that’s pushing everybody, including filmmakers into me, into HBO. It’s pushing everybody and that would include foreign films. The films that are actually made in their own countries – there are less French films made because their cinemas are showing more US films. I see that is happening because of a corporate reason, not necessarily because of an appreciation.

I think there is obviously this huge corporate machines making all kinds of movies whose intention is to make money. It’s sort of growing all over the globe so that these movies are occupying not only cinemas in the US, but in Italy when The Matrix comes out, all the screens are showing The Matrix. They’re not showing anything local. They’re not showing foreign films – I don’t know if they would anyway, ordinary Italian cinema. But there’s a sort of huge thing that’s pushing everybody, including filmmakers into me, into HBO. It’s pushing everybody and that would include foreign films. The films that are actually made in their own countries – there are less French films made because their cinemas are showing more US films. I see that is happening because of a corporate reason, not necessarily because of an appreciation.

Q: Did you ever get the chance to meet Kurt Cobain?

Van Sant: Yeah, I met him once because of a fundraiser that we were doing to battle an anti-gay issue in Portland called No on 9. He agreed to play a concert with Nirvana in Portland to support that.

Q: Did you have an impression of him at the time? Is your appreciation for him as an outsider? Or as a fellow artist?

Van Sant: I think as somebody who was a fellow artist who had made it very big but remained a Seattle artist. He was an acquaintance, not really somebody I was constantly in touch with. I did offer him a part in a film called Binky that winter, actually. I don’t know if he ever read it. Courtney said he read it, but I don’t know if he read the whole thing.

Q: The character is Blake and the film is inspired by Kurt Cobain, but throughout the whole film Blake’s wardrobe is very specifically Kurt Cobain clothing. Everything Blake wore is something we’ve seen Kurt in on TV or in a photo shoot. How important is the line between the fictional Blake and the real Kurt Cobain?

Van Sant: The concept was originally to be different and distance the character from Kurt, but I think that by the time we actually made the movie – the original movie I was going to make in 1995 or 1996 – but by the time we made it in 2004, everyone was sort of playing into this idea of what the reality was and what our film was. I had the choice to have that not happen and I had the choice to say that’s OK, and I guess I said that’s OK because I guess I got into it myself, how similar our character was with a real character. It’s a choice that was made.

It’s a fictional thing, it’s not supposed to explain literally Kurt’s last days but more poetically.

Q: How big a risk is that? Most moviegoers are used to having everything spoonfed to them and this movie does not do that. Where did you draw the line on telling people information?

Van Sant: I think that sort of could be said about Gerry and Elephant. They are all three made in a way that hopefully you’re somebody who is benefiting from allowing your own imagination to wander while watching the film. If not then – hopefully you’re not getting bored, but if you are the thing is not working. In the same way that too much information or the wrong kind of information might not work when I’m watching a movie, it might make me bored. The obvious has to be stated four times in a scene, you lose your own patience. There are different ways – you can look at it from too much information or not enough information.

The small amounts of information are hopefully meant to be – I used to call them tinctures, where you’re putting a tiny drop in a big bowl and it actually has a power on its own to create a chain reaction in your imagination.

Q: We hardly see Michael [Pitt]’s face for much of the movie. I’m sure that ties in to a lot of what you’re saying now – so what went into that decision?

Van Sant: You actually see him more than you think. A lot of time his hair is in his face, but there is a lot of time where you’re seeing him but there’s this feeling you’re not seeing him.

Q: There’s one thing we don’t see is heroin use, but it’s there. What was your decision to not show drug use?

Van Sant: I wanted to suggest it and not sort of tie it down to a specific drug and a specific method of preparing a drug. He was on something. Probably because I don’t have any idea that was exactly what was going on in those last three days or exactly what the methods were. I didn’t want to tie it down.

Also I guess that’s been seen enough to make that a cliché. If you see it, it does definitely work on you in a certain way as a viewer, the whole idea of seeing people using needles. It does distract you from what’s going on. That was my thing, so I suggested it but I didn’t want to go too far in that direction.

Q: With Finding Forrester you hit maybe the most mainstream and commercially-oriented film of your career and then you’ve followed it up with these three exceptionally non-mainstream and non-commercial pictures. Was that a specific career choice?

Van Sant: Yeah, I think probably Forrester was the end of a particular cycle I had started with Good Will Hunting and Psycho. Good Will Hunting was a low budget film and it became a bigger one, and then there were two big budget films, Psycho and Finding Forrester. I just thought I had the ability and the finances to do what I thought I wanted to be doing, which was scaling back. I always wanted to go back to the days of Mala Noche, when I had three people on the crew. I haven’t gotten there yet.

Q: But you’re going the opposite way from that now – you’re doing The Time Traveler’s Wife, which I assume is a bigger budget.

Van Sant: Yeah. That’s true, that’s playing right into the – but that’s only one project I have right now. It might happen, it might not happen. But it’s true. If it does happen, maybe I can make it in a certain way that would be more like Last Days was made. I’ve said that to the people I’m adapting it for. I’ve explained how I want to do it.

Q: What excites you about that material?

Van Sant: I think it’s a really nice book and it’s a departure from what I’ve been doing recently. It’s a job. It came from the outside, as opposed to something I thought up. It wasn’t a job as a job to do, but it just came from the ring of projects that are offered.

Q: But in the terms of the story, what do you find interesting?

Van Sant: I find that the sort of diagram of their relationship is nice and well done. If I can pull it off it’ll be nice. It’s hard to do. It’s hard to cast. In some ways, I think a love story – if you see the two people onscreen, it’s already happened, they’re there. That’s the hard part, to get there already. Telling the story is very hard, too, but it’s almost the chemistry with the film. The ones that don’t work you can tell, they’re doomed from the start. It’s interpreting chemistry. It’s scary but it’s a challenge.

Q: When you do these smaller films do you worry about making money? Are you able to go back to your investors and promise they can make their money back?

Van Sant: Yeah, they’re low budget so they don’t have to make that much money to survive. Gerry I  made with my own money, so that was the risky business venture. It took us a few years to get it all back, so we broke even basically. Elephant was one where I guess at the budget which we had, which was 3 million, it was somehow good for HBO. We could do a film that was challenging in its style. They knew what we were doing – I showed them Gerry, I showed them the script, I showed them the cast. In the end they made money off of it because they sold it to lots of different territories. Same with Last Days. They meet their requirements which they have for what their business thing is, which I’m not exactly clear on besides the fact that they’re providing programming for HBO.

made with my own money, so that was the risky business venture. It took us a few years to get it all back, so we broke even basically. Elephant was one where I guess at the budget which we had, which was 3 million, it was somehow good for HBO. We could do a film that was challenging in its style. They knew what we were doing – I showed them Gerry, I showed them the script, I showed them the cast. In the end they made money off of it because they sold it to lots of different territories. Same with Last Days. They meet their requirements which they have for what their business thing is, which I’m not exactly clear on besides the fact that they’re providing programming for HBO.

Q: Can you talk about your exchanges with Courtney Love regarding this movie?

Van Sant: I just called her and said that I wanted her to see it. She also wanted to know about it because she had been asked about. I described it to her, but as far as I know she hasn’t seen it. I walked her through it.

Q: Was she generally receptive?

Van Sant: She knew about the project from 1996, when I was working on an early version. Somewhere in the year 2000 she said she thought I should make the film. She’s always been supportive.

Q: Was there ever any thought of making this a straight ahead biopic?

Van Sant: That’s where I started out. After just considering a biopic I started working with what we have now, a kind of retracing of a supposed last three days in this guy’s life. Somewhere in the period when I was working on it I thought that maybe I should go back to the biopic idea and maybe do it with dolls. I was interested in doing a film with dolls. I’ve seen some really good films done with dolls that remove you from the reality so you can really objectively look at the story a little bit better. That would have been a more traditional showing the guy’s past, the band forming, the band firing three drummers and finally finding the perfect drummer, things like that. I wrote two pages of that and just said, forget that. I went back to this. It was going to be like Todd Haynes’ Superstar. That was going to be the model.

Q: Earlier this year a really great Criterion edition of My Own Private Idaho came out. What was it like to revisit that film, to look back at that part of your career and to look back at River Phoenix?

Van Sant: There had never been a DVD of My Own Private Idaho in the States. They had one in Australia, and I thought maybe they just weren’t interested in the film or they just didn’t envision sales. New Line owned it and they wouldn’t sell it to Criterion. At some point down the line Criterion talked them into it.

I had some things I helped on, like an interview with Todd Haynes. It was fun to revisit it. I thought the film held up, which I was happy with. It wasn’t particularly sad. I’m always confronted with River’s death – other than the movie itself, there are other things that bring it up.