Welcome, class.

Due to a variety of reasons stemming from trending, blatant cash-ins, and all-too-frequent voids of creativity, the horror genre is particularly prone to repetition. Yet individuals such as myself (and quite likely you) crave the fruits of the horror tree all the same. What others would call clichés, we call conventions. A cliché is something that has become trite with overuse; something we are tired of seeing. A convention is a customary practice, a rule. To us, horror films are like episodes of a favorite TV show. We tune in week after week specifically to bask in these familiar tropes, traditions, and archetypes. Here in Horror 101 we shall turn an academic eye on this vast world of horror movie conventions.

So come journey with me into the haunted recesses of one of cinema’s oldest genres. Don’t be chickenshit. No one has disappeared in here for years. Plus, I found this dusty old Ouija board we can get drunk and play with…

(Lesson 9 of 9)

It has been a long gory road, but we have finally come to our last day of class (before the big exam). In lieu of a pizza party, instead we’ll just scale it back a bit, take it easy and have some fun. Thus far we’ve been focusing on important archetypal characters, but there is so much more to the world of horror, so many other elements that have been become staples of the genre: plot-points, deaths, scare tactics, etc. So let’s kick back and wade through some totally random crap.

Corpse Art

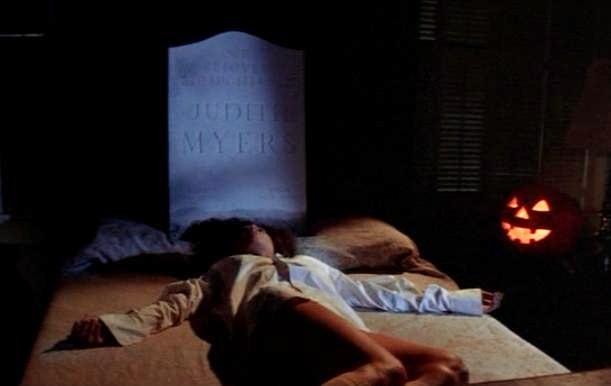

As we have discussed before, the great majority of Common Slasher movies follow a similar structure: our Slasher goes around killing all our Hero’s friends, one-by-one, until finally all those friends are dead. It is at this point that our Hero will return to the cabin (or what have you) to find all these corpses strewn about in very deliberate, often very elaborate ways – nailed to the backside of a door, or maybe rigged up to fall from nowhere when our Hero enters a room.

This is Corpse Art.

Corpse Art is proof that even the most mindless and depraved of killing-machines like to express themselves creatively. Where has the Slasher been hiding the bodies and when did he/she find time to execute all these elaborate set-ups? Who knows? But the Slasher is making a statement, and that statement is, “Hey, look, I killed all your friends.” Rather than just dump all the bodies in a big pile, our Slasher made a concerted effort to do something different, something interesting, something special for our Hero. Of course, our Hero never seems particularly amused by the handy work, usually just screaming and running away. I guess my college art teacher was right – art is to be appreciated, not enjoyed.

Though he didn’t invent Corpse Art, Jason Voorhees most certainly perfected it over the run of the Friday the 13th series. Part VII: The New Blood finds Mr. Voorhees feeling particularly inspired, giving Tina (Lar Park Lincoln) a veritable gallery showing of her friends and family all over the cabin and surrounding area.

The Flying Cat

In my three decades on this planet I’ve owned and been witness to many a cat. In fact, I’m currently cat-sitting two cats. No doubt, cats can be spooky. They will often freak me out by staring into a dark room, then suddenly running away for no discernible reason, making me wonder – should I run too? But not once, ever, has a cat flown screeching out of a cupboard or off a bookshelf at me while I was investigating the source of a mysterious noise. I don’t think cats do that. Yet inevitably, when anyone is nervously exploring in a horror movie – doesn’t matter if they’re in an alley, abandoned house, or a parking garage – a cat will fly out of no where, screeching or hissing, and scare the shit out of them.

Needless to say, the idea here is to scare the shit out of us too. It’s a fake-out scare.

While I refuse to call movies that rely solely on fake-out scares “scary,” I’m not against the device. But the Flying Cat should have been retired around 1980, yet people are still utilizing it today. How about someone’s pet parrot flies out of nowhere? That seems slightly more plausible.

Though it certainly didn’t originate the Flying Cat, I blame Alien (1979) for popularizing it.

The best part of the Flying Cat routine is that the cat “actor” in question is invariably and noticeably bracing itself for impact in a way no cat would if it had jumped by its own volition. So rather than being spooked by such a cheap scare, I’m merely left with the comically twisted mental image of some production goon, poised off camera, heaving this poor cat into the air take after take. Hmm. Wait a minute, I’m having an idea…

Final Take. Released 1980. This Crazed Animals film stars Farrah Fawcett as an actress working on a Hollywood suspense thriller. The film-within-a-film is about a woman who works at an animal shelter, so there are a ton of animal actors involved with the shot. And let’s just say this isn’t a film that will have a “no animals were harmed during this production” tag at the end of the credits. Animals are harmed during the shoot. And off the shoot, at the hands of their mean-spirited wrangler, played by Burt Young. Soon, the animals begin to fight back!

Okay. We can continue.

Self-Reflexive Gag Reflex

For those unfamiliar with the film/art theory term, “self-reflexive” refers to works that are marked by or making reference to their own artificiality or contrivance. Sometimes this can be hot heavy and the entire point of a film, like Rubber (2011). Other times it can be merely subtextual, like the proto-Slasher flick, Peeping Tom (1960). Further down the scale are films that simply bask in other films, which can certainly be used effectively, like the Tragic Slasher film, Fade to Black (1980). At the very, very bottom of the self-reflexive barrel are horror films that make lame in-jokes or in-references to other horror films. I’m not talking about Kane Hodder making a cameo in Jason Goes To Hell (1993). I’m specifically talking about characters in horror movies referencing real horror movies in their dialogue.

Unless it is part of the narrative theme, like Scream (1996), this is the laziest and most distracting way for a filmmaker to make an homage to other films. In the right hands it can work, but let’s be real – most horror movies are not in the “right” hands. While I’m sure some viewers enjoyed the references to Evil Dead and Peter Jackson in Dead Snow (2009), I thought the dialogue undercut the film’s reality and thus rendered the events weightless and tension-free. Self-awareness is a slippery slope for horror films. Even horror-comedies.

The other gimmick many horror filmmakers can’t see to resist is having one of the random idiots – making up our Mismatched Friends partying in the woods – a filmmaker or film student. And not just any filmmaker, a filmmaker who wants to make horror movies. Like Bill (Patrick Renna) in Dark Ride.

Monster Vision

Long before Jaws (1975) managed to forever link itself with the practice, shooting a scene from the monster’s POV has been an easy and cheap way around monster make-up and FX. Sam Raimi could never have made The Evil Dead (1981) without the technique. Even if your film does have the budget to go crazy, using POV is a useful way to prolong the revelation of what your monster actually looks like. When this can, and usually does, get ridiculous is when the film tries to show us a scene not just from the monster’s point-of-view, but literally through its eyes.

Shot in Glorious Monster Vision!

From Empire of the Ants (1977)

.

In theory this is a great idea. We’re getting treated to what the world looks like through some horrifying creature’s eyes. That’s novel, right? Well, this idea is unfortunately only good on paper.

Movies as a medium were designed to be viewed by us, human beings. How exactly does one show how a bat or snake sees in a 2D image projected onto a screen? You can’t, of course. You can only imply or give the impression of it. Trickier yet is when our monster is a fictional creature. What does a werewolf or a vampire or a giant-sea-beast’s vision look like?

The biggest clusterfuck with Monster Vision is that whatever visual effect the filmmakers are using to designate “Monster Vision” generally ends up making things difficult to see, for us. So what’s supposed to look “cool” simply ends up giving the impression that the monster has shitty eyesight.

The 80’s were a real boom for MV, because of the then recent advent of simple post-production video FX, giving us gems like Wolfen (1981), where the filmmakers decided that werewolves saw everything in crappy, cable-access grade music video FX (someone got a Video Toaster for their birthday!). The worst case of MV I can think of is from the movie Grim (1995), which looks like it was shot through a kaleidoscope someone won playing skee-ball, then tinted dark red to make things even more unperceivable. How Grim was ever able to capture his victims is beyond me. The dude is essentially blind.

Sci-fi tends to fare better when it comes to Monster Vision than horror does. For one, we’re usually dealing with robots, and Robot Vision is much easier to credibly pull off. The Terminator’s vision was classic 80’s shit MV (way too dark, way too red), but with all those numbers, scans, and various computery images whirling about, it at least made it passable.

Monster Vision is most effective when it’s actually part of the story, not just masturbatory “wouldn’t-that-be-cool” special FX. Predator (1987) is one of the only cases where Monster Vision was used really effectively. Arnie realized the Predator saw in heat vision, and thus wouldn’t be able to see him if he could mask his body heat. Though, really, that was the Predator’s Mask Vision. At the end, when the Predator takes the mask off, his actual vision makes absolutely no sense. Why is MV always red? Whyyyy?!

Seriously, what the fuck?

.

I realize the temptation must be strong for filmmakers to come up with an iconic MV. But it’s too risky. The shark in Jaws sees through a standard camera lens. Imagine that movie if Spielberg had tried to recreate “shark vision.” Think of how shitty Jurassic Park (1993) could have been if we’d had “T-Rex vision,” or if Joe Dante had pondered, “I wonder how a Gremlin sees the world?” Aspiring horror filmmakers of the world… just don’t do it.

The Lazarus Friend

You know the character. Usually he/she was the wacky sidekick or sassy best friend to the Hero, they died earlier in the film, and yet here we are, post climax, the Villain defeated, the dust is clearing, and in walks… the wacky sidekick?

I know what you’re thinking, “But I saw him die?” Yes, you did. What you didn’t know was that this wacky sidekick is also a Lazarus Friend, capable of self-resurrection. It’s a miracle!

The Lazarus Friend is a type of Straggler, but is not to be confused with a supporting character that we thought was dead, but returns during the climax to join the final battle. That’s different, A) because that character actually does something useful, and B) because it was planned.

The fact that the Lazarus Friend character survives the movie is totally irrelevant to its outcome, and generally was not planned. Those Stragglers who return during the climax, they always “die” in suspiciously ambiguous ways (e.g., falling off a bridge into the river). Our other characters just assume he/she is dead and then move on, but a savvy audience member will guess they likely aren’t. They rarely get decapitated on screen, if you follow me.

The Lazarus Friend often survives the film as an afterthought, likely because test audiences loved the character and were pissed off when they died. So the Lazarus Friend’s miraculous return is quite often a reshoot. Brandy’s character in I Still Know What You Did Last Summer (1998) is a classic Lazarus Friend. Her earlier death was absurdly violent for her to have survived, and it was widely publicized that her survival was a post-testing reshoot. Deputy Dewey (David Arquette) in Scream is another Lazarus Friend, though he was actually saved by the filmmakers, not a test audience.

The Tangential Music Video

Movies in all genres can be guilty of this crime, though it seems the most out of place in horror films. It always starts innocently, our Hero is in a bar or at a school dance with a band playing live music. Then before you know it, the focus of the scene becomes all about the band, and we’re in a Tangential Music Video – usually one with all sorts of dorky shots where the camera will pull in and out on individual band members, trying their best to look cool.

If the story/subject matter of a film calls for band showcasing – like New Year’s Evil (1980), about a music television marathon – that’s one thing, but more often than not it starts to feel strange when we take a several minute break from the narrative to listen to some shitty band. Generally this is done as filler to pad a film’s run time. Other times it is probably done to feature a band that is friends with the filmmaker. Then there are times when it seems like the filmmaker was secretly trying to make a musical, like Howling: New Moon Rising (1995), which makes the unforgivable sin of featuring more of its crap music then it does of the werewolf.

A totally egregious TMV sequence that surprisingly works is in Graduation Day (1981), featuring what I have to assume, based on the chorus, is the song, “Gangster Rock.” The sequence begins in a roller rink and then slowly morphs into a lengthy Slasher chase sequence. Far from stalling the narrative, it’s probably the best part of the movie.

Of course, the greased up sax player from The Lost Boys (1987) gets a pass too.

The Black Best Friend

In modern horror movies, a white female Hero will seemingly always have an African-American best friend. Doesn’t matter if the movie is schlocky (I Still Know What You Did Last Summer; Scream 2, 1997) or classy (Candyman, 1992; The Skeleton Key, 2005) the Black Best Friend is a staple. And she is usually sassy.

I’m all for adding ethnic diversity to the honky-fests of Hollywood (why not just make the Hero a black gal sometimes?) but they never seem to have Latina best friends, or Indian, or Chinese, or Pakistani. Given the ratio of whites and blacks in the country, it’s statistically impossible for all white women to have a black best friend, unless all black women are best friends with like 10 different white chicks. Personally, I’m pulling for an Eskimo Best Friend. Eskimo!

The Incredulous Cop

Here is something you will never see in real-life…

A cop is sitting in his car, on patrol. From out of the woods comes a sweaty and beat-up teenager, with traces of blood on their clothes. They can barely breathe, there is a panic in their eyes no actor could pull off. “Help! Someone is trying to kill me!” they scream.

Then the cop, an annoyed look in his eye, replies, “Gimme a break…”

As we discussed in our Victim Pool lesson, it is an on-going issue for horror movies to deal with police proximity. You don’t want the Hero to be able to get help from the police. Having the Hero stuck out in the woods usually solves that problem. But what if they’re in an area where they can reach the police? Simple. Have the officer manning the front desk of the police station be an Incredulous Cop.

“Have you kids been drinking?” is probably the IC’s catchphrase. This guy is willing to stake his job and the lives of several citizens on his prejudice belief that all teens/college kids are substance abusing liars. Sometimes this aggressive skepticism is given a context, like Sheriff Garris (David Kagen) in Friday the 13th Part VI: Jason Lives (1986), who has the motivation of not wanting rumors of Jason Voorhees getting stirred up again needlessly. More often than not though, the IC is just a skeptical asshole.

The Teleporting Slasher

We’ve all seen the moment a million times. Someone, we’ll say a girl, is running as fast as she can through the woods, away from our Slasher. She keeps looking back over her shoulder to make sure the Slasher isn’t gaining. He isn’t. In fact, he isn’t even running as fast as she is. So the chase continues. She keeps looking back, keeps running, until – BOOM! She runs right into the Slasher. How the hell did he get in front of her? He was jogging! Simple. Most Slashers seem to possess the ability to teleport.

Teleporting comes in handy everywhere, not just in the woods. Why chase your victims down the stairs of the house when the filmmakers can merely keep you off-screen long enough that they decide you could have conceivably found an alternate route? As a Slasher it really helps improve the overall tone of your attacks if we know you can move around like the Flash. Sure, some might say this isn’t actually a superpower, just sloppy, even incompetent filmmaking, but since Jason Voorhees can do no wrong, it must be the real deal. Next you’ll say that Corpse Art isn’t actually artistic expression.

As with all things Slasher, Jason is the master. He didn’t start out with the ability to teleport, but slowly developed his teleporting powers over the first handful of Friday films, finally perfecting the process in Jason Lives, when he became Jasonstein. From that point on (not counting the remake), Jason couldn’t be bothered to exert himself with running. He had to conserve his energy for punching off heads and breaking people in half.

Terror Train (1980) has possibly the most illogical use of a Teleporting Slasher. What is so illogical? Our characters are on a fucking train! You can only move forward and backward! How the Slasher manages to sneak around so efficiently and quickly can really only by explained through teleporting. Scream of course took this foible and made it part of the twist, explaining Ghost Face’s teleporting as being the work of two Slashers wearing the same costume.

.

Well, that is that, class. Make sure to study up, and I’ll see you back here next time for the final exam!

.

The Solo Hero

The Couple

The Stragglers

The Guy Who Knows Things

The Jokester

The Victim Pool

The Slasher