Kotaku editor Stephen Totilo has issued an editorial announcing significant changes to the focus of the popular gaming site’s coverage:

“The future of games coverage is in the present. For too long gaming coverage has focused on the vague future, the preview mindset of possibilities and maybes. And when it’s involved the present it has been drenched in the dreary falseness of empty interviews, bland producer-speak and executive-hype. It’s neither been real enough nor true enough to what is actually happening now. For too long games reporting has involved staring at what is opaque, maybe glimpsing something through it and reporting about that possibility, all the while ignoring so much of what is clearly visible and exciting around us.

I believe there is a better way to cover games, one that puts future-based coverage and executive interviews in proper diminished proportion. We must focus on the games that are being played now and the human beings—the gamers, mostly—who are doing interesting things with them.

Millions of people are playing games right now. They are having amazing experiences in these games. They are discovering fascinating, crazy, and/or scandalous things in them. They are celebrating funny discoveries and raging at emerging bullshit. They’re doing this on YouTube and Twitch, on Reddit and on forums. They do it here, too, though we’ve not given them much space to do so. Most of this is missed by the games press, however, because the games press focuses too much on covering games before the real world touches them and too little after games are released. Exhibit A in that is that people are assigned by their editors to play and write about a game before it comes out in order to review it and are just about never assigned to do so afterwards. They abandon writing authoritatively about a game as soon as it is released. This is archaic and an insult to gamers. This is changing at Kotaku as of now.”

Totilo goes on to explain that in the future, Kotaku’s writers will be assigned games to cover post-release, citing their continuing coverage of Mario Kart 8 and its continued coverage of the evolution of the game and its community:

“Typically, we would have probably only covered the game’s downloadable content announcements, because that kind of “news” comes easy, via a press release from Nintendo. Instead, we’ve offered the kind of stories that a game company wouldn’t ask us to cover but feel vital to telling the story of Mario Kart 8 and the community of gamers playing the game. This feels right, and it feels more relevant than simply doing a bulk of Mario Kart 8 coverage prior to release—covering Nintendo-administered preview demos, E3 announcements and such.”

Anyone who’s been following my thoughts on the matter will not be surprised to know that not only do I think Kotaku have made the right choice, but that this what I believe to be is the future of games journalism. It’s a future that can’t come soon enough as far as I’m concerned.

I truly believe that this is the greatest time to be writing about games, with the medium growing in confidence as it transcends entertainment and begins to explore its potential as a genuine part of culture. Unfortunately, the field of games writing has been slow to adapt to this, chained to a paradigm that has barely evolved in twenty years. The industry has long laboured at the yoke of pre-release mania, driven by the generation of previews and reviews not only to satisfy the publishers wanting to see their games promoted, but an audience raised to believe that games can only be written about in a preview-review cycle.

I truly believe that this is the greatest time to be writing about games, with the medium growing in confidence as it transcends entertainment and begins to explore its potential as a genuine part of culture. Unfortunately, the field of games writing has been slow to adapt to this, chained to a paradigm that has barely evolved in twenty years. The industry has long laboured at the yoke of pre-release mania, driven by the generation of previews and reviews not only to satisfy the publishers wanting to see their games promoted, but an audience raised to believe that games can only be written about in a preview-review cycle.

Slowly, this idea has changed. The rise of the Internet has meant that word on the quality of major releases often leaks out to gamers before release date, embargoes be damned. Then came the YouTuber, and suddenly you could base your purchasing decisions based on hours of footage of an actual game in action, rather than the abstracted description in a review or disseminated PR material.

In the meantime, that’s left the press suffering an increasing sense of limbo. Contrary to popular belief, the games press has never existed as a PR wing for the publishers – at least, the corners of the games press worth following. Yet there’s a large chunk of the Internet that harbour an almost fanatical commitment to the idea that press and publishers really do exist as some dastardly anti-gamer Ouroboros, with its loudest proponents often being the ones with the least idea of what the job is actually like (As nicely laid out by popular commentator and ex-games journalist Matt Lees in this blog post).

But at the same time the dissent does stem from valid questions about how the games media has always operated. When your entire industry is in lock-step following the hype cycle and the advance review copy becomes the golden calf, only for a game to lose all perceived editorial value once the review is written and released to the public, it makes for an industry constantly chasing its own tail and gives publishers a disproportionate amount of power. While cases of actual corruption are rare, it can’t be denied that in the past the line between publisher and media has been a thin one. The brutal truth is that games media has always relied on reviews because they’re the principal source of the traffic that keeps it in business, and the dance between honest reporting and keeping publishers onside (thus avoiding the dreaded review copy blacklist) is one that is both difficult and perpetual. Outlets need reviews more than the publishers do, and publishers have often exploited this advantage with the promise of review exclusives and similar incentives (Of course, what also needs dismantling is the traditional reliance on publishers for advertising revenue, but let’s take one hurdle at a time here).

Of course, the louder corners of the Internet may love bemoaning game reviews, but that hunger for the things – even if for soapbox fodder – ironically perpetuates outlets’ reliance on them for the clicks that keep them in business. But isn’t that just a natural assumption based on what we’ve always known the industry to be? We’re all hardwired to focus on reviews, and see them as the be-all-and-end-all of the judgement of a game’s worth. But gamers are starting to realize what film and popular music fans knew decades ago, and lovers of literature and theatre have known for centuries: that reviews don’t mean a lot in the long term. They’ll always be valuable as an indication of the general quality of a game at launch, and unfortunately will impact developers financially until publishers’ vulgar obsession with Metacritic runs its course, but works with merit will have a life far beyond a vertical slice of opinions snatched from a brief moment in time.

However, this isn’t just about reviews; it’s also about the writing itself. The perennial obsession with future releases and exploiting the New Shiny while it’s still hot also makes for a pretty shallow creative well upon which to draw, promoting formula over invention and conformity over heart. Yet there’s a cultural imperative at play now that didn’t really exist for games in the past. As the first gamers from the 70s and 80s get older, so grows the recognition of the medium’s potential as a part of culture, and idea that so far has had no significant commentators to chart it simply because it’s taken the better part of thirty years for everyone to realize that games had even arrived to culture.

However, this isn’t just about reviews; it’s also about the writing itself. The perennial obsession with future releases and exploiting the New Shiny while it’s still hot also makes for a pretty shallow creative well upon which to draw, promoting formula over invention and conformity over heart. Yet there’s a cultural imperative at play now that didn’t really exist for games in the past. As the first gamers from the 70s and 80s get older, so grows the recognition of the medium’s potential as a part of culture, and idea that so far has had no significant commentators to chart it simply because it’s taken the better part of thirty years for everyone to realize that games had even arrived to culture.

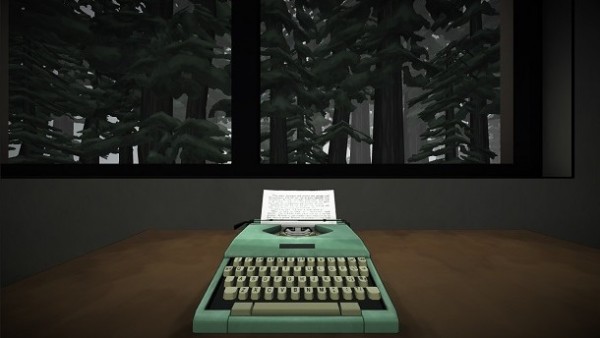

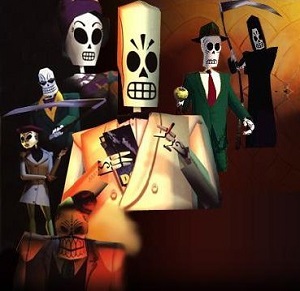

I’ve been writing about film and the arts on a freelance basis for just over a decade now, and it’s only recently that I realized the place gaming has had in my own life and that I could write about games the same way I write about cinema or music. My experience is very much like that of a lot of you reading this: I grew up with games, reached adulthood, maybe even thought once or twice that I was too old for this videogame stuff and put the hobby aside… only to find that I’d always end up getting into them again. After a while I realized that games weren’t just a thing I do to kill time: they were part of my cultural landscape, as ingrained in it as the movies I watched, the books I read or the music closest to my heart. Then it suddenly seemed that the games themselves were starting to realize this, becoming increasingly sophisticated on a creative level. Grim Fandango, Half-Life, Knights of the Old Republic, Red Dead Redemption, Gone Home, The Last of Us – milestones that showed me how games were slowly but surely learning to tell stories, employ cinematic language and world building, tackle theme and social issues, slowly becoming just as valid a source of art as music, film or literature. The medium is, frankly, still getting there, but in the last four or five years we’ve seen these strides get wider and more confident.

Gamergate, for all the ugliness that came with it, did have one massively positive effect: it pushed games’ increasing social awareness to the forefront, and raised the question not only of what games writers do, but what they can do, and what they can do is the job of any good critic: engage with the culture at hand. That means abandoning the traditional style of games writing, which has for the last thirty years been pitched at a fourteen/fifteen year old audience. Games are now older, gamers are older and this will no longer do. It’s time for a more analytical and observational perspective, for real critical praxis to take the reins.

I mean, it’s not like there isn’t an abundance of culture to talk about. There’s the fans, how they enjoy and adapt the games they love; flashes of genius, such as YouTuber gbbearzly’s spectacular Dark Souls playthroughs using a Rock Band guitar; the rise of games tackling contemporary social issues, such as Gone Home, Depression Quest and The Cat Lady; post-mortems of major releases exploring the practical, financial and artistic triumphs and constraints experienced by game developers; in-depth analyses and critique of games on a technical and narrative and literary level (such as in CHUD’s own Storytime with MCP series). There is basically a whole culture out there, one that has been largely ignored in the frenzied pursuit of the hype cycle yet is infinitely more interesting, and will ultimately shape the future of games journalism far more than a commercial system that is already well on its way to obsolescence.

Gaming has reached an age where it has finally realized that it is here to stay, and the question becomes ‘Now what?’ For many of us gamers, we’re asking ourselves that same question. Games are part of our cultural landscape, just as much as any other artform. We’re only just realizing that they can just maybe possibly be art, can hold significance past entertainment or guilty pleasure. Our tastes may have matured, but we didn’t grow out of this thing. So surely it stands to reason that we would naturally want to read writing about our games that treats us like the mature, culturally engaged people we are?

Gaming has reached an age where it has finally realized that it is here to stay, and the question becomes ‘Now what?’ For many of us gamers, we’re asking ourselves that same question. Games are part of our cultural landscape, just as much as any other artform. We’re only just realizing that they can just maybe possibly be art, can hold significance past entertainment or guilty pleasure. Our tastes may have matured, but we didn’t grow out of this thing. So surely it stands to reason that we would naturally want to read writing about our games that treats us like the mature, culturally engaged people we are?

What Kotaku have recognized is that games writing is undergoing just as profound a paradigm shift as the medium itself. As cinema and rock music grew out of their simplistic, entertainment-focused roots to branch out in increasingly adventurous and avant-garde ways, so did the criticism that charted their development. This eventually led to the emergence of names such as Lester Bangs. Pauline Kael, Roger Ebert, Steven Wells – critics who not just engaged with the technique of criticism and analysis with exceptional verve and intelligence, but were possessed of an artist’s flair of their own. People like this raised criticism in their fields to an artform, enriching the culture and showing that those that unpack and contextualize art can be heroes alongside its creators. Gaming doesn’t have equivalents of these pioneers yet, but it’s getting close with commentators such as Jim Sterling and Matt Lees are becoming increasingly known not just as personalities, but as authorities – an important distinction, and one that whose advent is more than welcome. In many ways, these guys are ahead of everyone, providing commentary that often far outstrips what the major outlets have managed. This is precisely because they’ve abandoned the traditional chase of the hype cycle and directly addressed games as a cultural phenomenon, encompassing issues that affect gamers that the traditional press have done precious little to explore.

We’re living in an exciting time, a time which is seeing games beginning the same metamorphosis cinema and rock music went through in the 20th Century – that of growing out of mere entertainment and novelty, and becoming its own cultural force. The games writers of today are lucky, really – I mean, writing about culture is one thing but how often do you get to be there when an artform comes into its own? I see a future where the best writers will not be judged by how entertainingly they can talk about the upcoming game of the moment, but by what they actually have to say. As someone who has only really just embarked in what I hope is a long career in the field, that would suit me just fine.