Is it real?

Maybe it’s silly that so many people asked that question of The Blair Witch Project 15 years ago, but make no mistake, that was a major selling point for the film. Sure, a lot of people wanted to see what a $15,000 movie looked like, but when rumors started circulating about VHS tapes left in parking lots—before any film festival screenings—the chill that ran up everyone’s spine came from the possibility that they might be watching something real. A horror movie come to life. Since then, found footage has become so commonplace as a genre, that the question of authenticity is a complete non-starter. It’s not real and it never was. By sticking a camera in every darkened hallway, we didn’t expose a nest of ghosts, we just confirmed what we already knew: dark hallways, while creepy, are empty. The glimmer of an authentic experience got snuffed out by the new film grammar that promised to provide it.

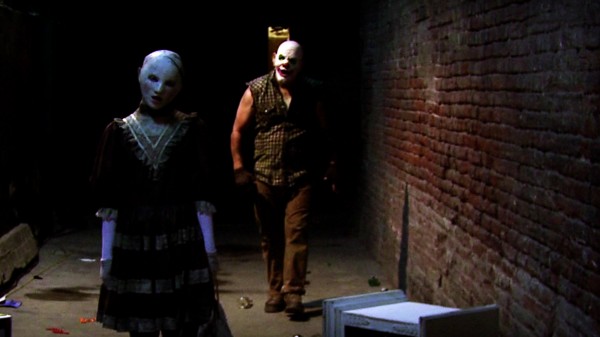

The Houses October Built is a film in search of an authentic experience. Or it’s characters are, anyway. They’ve heard the same urban legends that most of us have: some of the Halloween corn mazes or “haunts” use real dead bodies as props*. Or that the people who work there really are homicidal maniacs who’ll take the scare too far and kill you before you make it to the exit. So they rent an RV, equip everyone with a camera (we’ve come a long way since 1999) and head off into the “backwoods” in search of an “extreme haunt.”

Of course, they find it.

Like David Fincher’s The Game, it’s easy to start second guessing things we should already know (i.e. “Is this really a game?”) and I’m happy to say, this is what the film does best. This is much more of a psychological thriller than I ever expected it to be, mostly because that’s not something the sub-genre tries all that often. Common sense dictates that “found footage” is objective, rather than subjective, making it a bad match for anything other than cheap jump scares. That’s wrong, of course. We’re only ever seeing the shallow perspective of the camera, which is the definition of subjective. For some strange reason, we very rarely see it that way. So even when we’re told over and over again, that the experience these characters are seeking is nothing more than an extreme haunt, when the “scares” leave the confines of the haunted houses, we—like the characters—shift our perspectives. This is real.

But why would it be? That’s the dramatic push and pull that the movie gets really right. When you asked to be fucked with and you are, what do you expect? Sure, the main characters see a few haunt workers wearing the same masks—giving the appearance that they’re being followed from state to state—but these are masks sold all over the country. Why couldn’t these be different people? Is it more likely that there’s a shadowy syndicate of carnies luring people into deathtraps because—what?—they wanted to be scared? Or is it possible that when you actively seek out fear, you find it. By the end of the film, the answers are a little more definitive than I might have liked, but this is far more ambitious than it has any right to be, so I’m giving it a pass.

Shockingly, the biggest problem with the film is the haunts. On paper, it makes all the sense in the world that—like a walk through a Halloween maze—these scenes would be full of jump scares to goose the audience. Unfortunately, they just don’t work that way. There’s too much visual incoherence and the majority of these scenes play out like a YouTube video shot from the front seat of a roller coaster. You understand that the people on the ride are having a great time, but the experience is non-transferable. That’s going to make or break a first viewing of the film. People expecting a jump-scare-generator are going to be disappointed by the lack of anything viscerally frightening, flat out.

The scares may not translate, but the cast does a great job, first in selling their decades-long friendship and later with their confused journey deeper into…whatever it is. They keep the soap bubble that is the film’s high concept intact right up until the end. When they’re asked to take another step forward into something that could either be a trap or the thing they’ve crossed many state lines in search of, the schism feels earned.

The Houses October Built isn’t the scariest film of the year, but it’s not trying to be. The final note we’re left with isn’t a jump scare. Even though the film is ostensibly about those kinds of scares, it’s more interested in who makes them and—even stranger—who seeks them out.

THOB opens this Friday in theaters and on VOD.

*That dead body thing, by the way…that’s real. It happened in Long Beach, where I live.