I’m pleased to have seen this film at the wonderful Savannah Film Festival, where Bruce Dern received a well-deserved lifetime achievement award.

Plain speak and pragmatism coat the people and places of Alexander Payne’s Nebraska. The black and white photography wisely abstains from competing with the earnestly captured local color of these tiny Midwestern towns as Payne works with professional, local, and non actors to tell this story. The result is emotionally vivid and texturally authentic and quietly profound. More plainly, it’s real damn good.

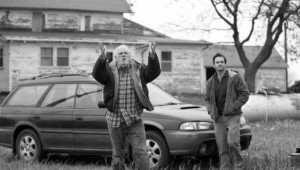

Bruce Dern plays a man we meet walking on the shoulder of a highway on-ramp with a purposeful, arthritic gait. He’s heading to Nebraska to claim his million dollars promised by a bullshit contest mailer. Or maybe he’s walking to get attention, or to get some time away from his wife. It’s all of them really, but he immediately attracts the attention of a police officer who gently investigates. This if the first of a number of beautifully anecdotal scenes that paint a perfect portrait of the Grant family- Mom, her two sons, and Woody, whose confusion is getting just about out of hand. Before long we’ve met Will Forte’s David, who drives the film (literally, for much of it) as the son who is just seeming to realize he’s fast approaching life-long mundanity. It’s a very fine dramatic performance from Forte, further suggesting his dramatic career will be as rich his comedy. His brother –Bob Odenkirk reminding people he can do earnest just as well as sleazy– has made good as a local newsman, but is the more distracted sibling. June Squibb is utterly remarkable as Kate Grant, the matriarch who is a steady fountain of nagging complaints and yet is never not entirely endearing. (Dern is of course the film’s warm center, but Squibb should receive every bit as much attention for her work and any justice means some of it manifests as statues.)

Another incident later and David agrees to cater to Woody’s delusion and drive him the two days to Nebraska, and we have a movie.

Though it flirts with being a road trip movie, David and his father settle for a while in the latter’s home town on the way. From there Payne masterfully unfolds scenes of subtle humor, small town passive aggressivism, and familial frustration that will play awfully familiar to anyone with a branch of rural-settled, aging family. I was particularly struck by a tableau of eight men melted into couches and chairs, quietly staring at a Football game as three aunts and grandmothers do church gossip over dishes. Swap  out football for NASCAR (unless Georgia is playing) and I’ve watched this exact scene on every cousin’s birthday my entire life. Payne nails the strange tone with which rural folks manage to speak their minds with unfettered abruptness, and yet can remain completely mysteries.

out football for NASCAR (unless Georgia is playing) and I’ve watched this exact scene on every cousin’s birthday my entire life. Payne nails the strange tone with which rural folks manage to speak their minds with unfettered abruptness, and yet can remain completely mysteries.

The meat of the film comes as Woody and his son spend more time in bars and meet more people from his past. Small bits and pieces of informational and stories remembered differently by different people start bringing David’s father into focus for him. As these new shades are revealed, we in turn learn how little he knows about the man, and get a sense of how weak the relationship really is. The shadow of alcoholism –the kind that breeds detachment and passivity rather than abuse– hangs over much of this, and the portrait of Woody begins as one of an ineffective, weak man. More stories and small adventures widen that image considerably though, leading towards the most honest, simple, and brave catharsis I’ve seen in a movie in some time.

Nebraska is not couched in your standard cinematic sentimentality. Neither David nor the film have any illusions that Woody has long left, making this film about scratching out a little bit of dignity, a little bit of connection with your heirs a moment or two before it’s too late. This doesn’t mean deathbed exchanges or tearful confessions. After all, this is a film made my people who have accepted an R rating just to leave the word “cocksucker” in the film, as it’s so brilliantly uttered by Dern. Where other movies would have overwrought monologues, writer Bob Nelson is content to let a single sentence do the work. Have you ever spoken much with a retired Korea vet who lives in a flyover state? You’d be a fool to think you’re ever going to get much more out of one at any given time. But the right sentence at the right time in the right place? That can altar an entire relationship in this world.

Nebraska is not couched in your standard cinematic sentimentality. Neither David nor the film have any illusions that Woody has long left, making this film about scratching out a little bit of dignity, a little bit of connection with your heirs a moment or two before it’s too late. This doesn’t mean deathbed exchanges or tearful confessions. After all, this is a film made my people who have accepted an R rating just to leave the word “cocksucker” in the film, as it’s so brilliantly uttered by Dern. Where other movies would have overwrought monologues, writer Bob Nelson is content to let a single sentence do the work. Have you ever spoken much with a retired Korea vet who lives in a flyover state? You’d be a fool to think you’re ever going to get much more out of one at any given time. But the right sentence at the right time in the right place? That can altar an entire relationship in this world.

Like all of Payne’s films, a sense of place is terrifically important, and no scene is not perfectly staged in a quaint, cluttered home or spare, aging dive bar. It’s obvious this story –which has been gestating between Payne and co. for nearly a decade– has been affected by the changing times. The erosion of –if not the American Dream proper– that particularly American confidence in the directly proportional relationship between hard work and happiness seeps in at the edges. These people are getting old, so are their towns, and those of the next generation that have stuck around are not at ease. But whatever larger subtext you want to apply, none of it is as potent or interesting as what the film does with the meaning of being old, being a father, and being a son.

Nebraska is a timely American film, but it’s built on an incredibly rich core of honesty and insight into family that I must imagine translates more widely. All of us have things we wish we could say or wish others knew about us and, honestly, how long have any of us really got?

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars