BUY IT: STEAM, WEBSITE

PLATFORM: PC/Mac/Linux (Steam)

PRICE: $19.99

DEVELOPER/PUBLISHER: The Fullbright Company

As gaming’s march towards higher storytelling standards continues unabated, so has changed the perception of how they should approach this goal. First, games wanted to be like movies; then, for a while, they wanted to be movies. In recent years, however, developers’ thoughts have progressed to a less imitative and more literary level, and scrutiny has turned to what games already are, how they can be used to tell stories that subsist on emotional truth as well as fantasy, and how to subvert or refocus well-worn mechanics to tell different kinds of stories. Some games, like Spec Ops: The Line, have framed expected mechanics in a new light; others, such as Dear Esther, have reduced mechanics to their most basic levels to make the narrative the defining substance of the play experience.

Enter The Fullbright Company and their debut game, Gone Home. Created by Steve Gaynor, creative lead on the fantastic Minerva’s Den DLC for Bioshock 2, the game tackles the main criticism that has dogged that franchise up to and including this year’s Bioshock Infinite – ‘Do we really need all the shooting?’ – and tackled it head-on.

It is 1995, and you play as Kaitlin Greenbriar, returning from a year spent traveling around Europe. You walk up to the front porch of the new family home, a country mansion bequeathed to her father by his estranged uncle, and are greeted with a hastily handwritten letter from your teenage sister Sam telling her that she’s gone, and not to worry.

It is 1995, and you play as Kaitlin Greenbriar, returning from a year spent traveling around Europe. You walk up to the front porch of the new family home, a country mansion bequeathed to her father by his estranged uncle, and are greeted with a hastily handwritten letter from your teenage sister Sam telling her that she’s gone, and not to worry.

Mysterious disappearances, portentous notes and a shadowy mansion on a stormy night? Nah, nothing to worry about here.

The game is first-person, but there’s no combat. Instead you explore this unfamiliar new house, gradually piecing together the truth through examining an almost ridiculous number of interactive objects. Mugs, papers, cassette tapes, ornaments, etc. Fullbright present a concept of a house as an evolving document of the lives within, and this house yields more than Katie could ever bargain for. It’s to Fullbright’s credit that these objects not only do a highly effective job of telling the various stories woven throughout the house, but are never less than a joy to read – even as it becomes quickly apparent that terrible things have happened in this place. The design work matches the level of the writing, creating an at times almost overwhelmingly oppressive and creepy atmosphere with only one jump-scare to be had (and it’s a doozy, too). This is assisted by Chris Remo’s beautiful, subtly looming score; funny how these Idle Thumbs guys are involved in all the best narrative games lately.

Though you control Katie as she explores the house piecing together her family’s fate, Gone Home’s real protagonist is Sam, who tells you her story of sexual awakening and forbidden love through narrated journal entries, beautifully performed by Portland actor Sarah Grayson.

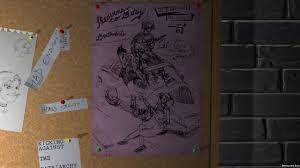

The choice of time period is key to Sam’s story. More than easy nostalgia value, or an excuse to not have to worry about pesky cell phones or digital communications spoiling the mystery, it represents a time that saw a generation come of age. It was the time of the Riot Grrrl, of the choice made by the youth of the day to start rejecting much of the sexual and gender orthodoxy that had previously been mainstream. It was the kind of time that defined lives, and we feel every last joy felt and every last wound suffered by Sam on her road of becoming. Combined with the growing sense of a darkness at the heart of this house, Katie’s apprehensive journey starts to reflect the fear and uncertainty her sister went through and it doesn’t take long until we start dreading the end to this vulnerable young girl’s story.

The choice of time period is key to Sam’s story. More than easy nostalgia value, or an excuse to not have to worry about pesky cell phones or digital communications spoiling the mystery, it represents a time that saw a generation come of age. It was the time of the Riot Grrrl, of the choice made by the youth of the day to start rejecting much of the sexual and gender orthodoxy that had previously been mainstream. It was the kind of time that defined lives, and we feel every last joy felt and every last wound suffered by Sam on her road of becoming. Combined with the growing sense of a darkness at the heart of this house, Katie’s apprehensive journey starts to reflect the fear and uncertainty her sister went through and it doesn’t take long until we start dreading the end to this vulnerable young girl’s story.

Sam may well go down as the most well-drawn and evocative character in video games this year, maybe ever. Square Enix pumped months of hype, multiple millions of dollars and enough virtual gore to fill several Manhunts into trying to convince gamers to feel the slightest wisp of concern for Lara Croft’s wellbeing; Gone Home eclipses this, for a teenage girl we don’t even get to meet onscreen, in the space of a couple of hours.And that’s even before a denouement involving an emotional rollercoaster of the kind I don’t think I’ve ever experienced in a game before.

But Fullbright’s wonderful character work doesn’t stop with Sam; while her story is the primary narrative thread, it is one of several stories we learn to varying degrees of specificity. There’s her father Terrence, the author of an unsuccessful series of time-travel thrillers (Blatantly fashioned by the developers as a cheeky riff on Stephen King’s 11/22/63) whose fractured relationships with his father and uncle have reverberated negatively throughout his relationship with his family; her mother Janice, whose career is on an upswing in inverse proportion to her happiness at home; the late Oscar, an inscrutable figure reduced by some unexplained tragedy, and the mansion that became his refuge then living tomb, known colloquially as ‘the psycho house’. And then last of all there’s Katie herself, whose long trip overseas feels increasingly less of an adventure but an escape.

But Fullbright’s wonderful character work doesn’t stop with Sam; while her story is the primary narrative thread, it is one of several stories we learn to varying degrees of specificity. There’s her father Terrence, the author of an unsuccessful series of time-travel thrillers (Blatantly fashioned by the developers as a cheeky riff on Stephen King’s 11/22/63) whose fractured relationships with his father and uncle have reverberated negatively throughout his relationship with his family; her mother Janice, whose career is on an upswing in inverse proportion to her happiness at home; the late Oscar, an inscrutable figure reduced by some unexplained tragedy, and the mansion that became his refuge then living tomb, known colloquially as ‘the psycho house’. And then last of all there’s Katie herself, whose long trip overseas feels increasingly less of an adventure but an escape.

Gradually a thematic foundation develops out of the idea that a family’s dynamic is often best understood not when they are together, but from the things they don’t tell each other. Coming from a Northern English family, where stoicism is in the blood and visible emotion is often a no man’s land, I could see a lot of myself and my own family in the Greenbriars. I recognized that hesitance belying love, and identified just as much with Terrence’s fumbling, insecure attempts to cross those divides as I did Sam’s need to escape it and find something of her own. I’ve done both, in my own way; I still do. Gone Home explores the tension between family and the members’ individual lives and secrets, how these dynamics dictate these levels of secrecy, and whether it really matters in times of need.

That’s not to say that Gone Home is completely without flaw. The game regularly experiences frame-rate hitches despite not being especially complex in terms of visuals or action. The game also doesn’t completely do away with the more convenient videogame tropes. Sam’s journal narration plays a little fast and loose with digesis. Fullbright gives them a plausible place in the world, but it’s an example of occasional moments when what the player learns and what Katie should or should not know at this specific point slip slightly out of sync. Conveniently locked doors and scripted events also occasionally pop up in the name of guiding the player to the next narrative hot spot.

That’s not to say that Gone Home is completely without flaw. The game regularly experiences frame-rate hitches despite not being especially complex in terms of visuals or action. The game also doesn’t completely do away with the more convenient videogame tropes. Sam’s journal narration plays a little fast and loose with digesis. Fullbright gives them a plausible place in the world, but it’s an example of occasional moments when what the player learns and what Katie should or should not know at this specific point slip slightly out of sync. Conveniently locked doors and scripted events also occasionally pop up in the name of guiding the player to the next narrative hot spot.

The question that needs to be asked, however, is whether these tropes really matter if they’re in service to an overall experience. Legendary architect Le Corbusier described a house as a machine for living in. Fullbright’s house is a machine for delivering the narrative, balancing drama, humour and mystery with impressive restraint. Because of this, however, its story operates under clearly-defined restrictions: it implies enough to suggest why some doors are locked to avoid dissonance (And maybe send a chill down the spine when you figure it out), but those who equate ‘exploration’ with ‘free roam’ may have problems accepting the guidance built into the game’s design.

Gone Home is an important game, but it isn’t going to be loved by everybody. It’s going to take some out of their comfort zone, narratively, aesthetically and mechanically, to places they won’t feel is appropriate for games to go, or where they feel games simply don’t suit. Others will feel cheated for paying $20 for a two-to-three hour game, or by the way the developers employ certain tropes to manage player expectations.

Gone Home is an important game, but it isn’t going to be loved by everybody. It’s going to take some out of their comfort zone, narratively, aesthetically and mechanically, to places they won’t feel is appropriate for games to go, or where they feel games simply don’t suit. Others will feel cheated for paying $20 for a two-to-three hour game, or by the way the developers employ certain tropes to manage player expectations.

But ultimately, Gone Home triumphs because it doesn’t take the beaten path, even when it seems to be. Many have this idealized view of games ‘growing up’ and ‘becoming art’ just by doing the same old stuff in a more palatable package, but the truth is that artforms grow through challenging traditional notions and defying expectations. It’s a journey into the heart of small but fiery lives, a journey that strips the cushioning off the mundane and reveals the life-changing dramas within. It is a journey gamers have never quite taken before, and one the industry may never forget.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars