He worked with John and Alan Lomax at the Library of Congress in the 1940s. He co-founded the Almanac Singers with Woody Guthrie. He adapted and co-authored the definitive protest song of the twentieth century – a little ditty you’ve probably heard called "We Shall Overcome". As one of The Weavers, he seeded the 1950s – 1960s folk movement, mentoring such young artists as Bob Dylan, Peter, Paul & Mary, Joan Baez. He appeared before the House Un-American Activities Community in 1955, refused to invoke his Fifth Amendment rights (or discuss his very public involvement in the Communist Party of the United States of America), and was blacklisted for his troubles. He’s led the way in the clean-up of the Hudson River.

He worked with John and Alan Lomax at the Library of Congress in the 1940s. He co-founded the Almanac Singers with Woody Guthrie. He adapted and co-authored the definitive protest song of the twentieth century – a little ditty you’ve probably heard called "We Shall Overcome". As one of The Weavers, he seeded the 1950s – 1960s folk movement, mentoring such young artists as Bob Dylan, Peter, Paul & Mary, Joan Baez. He appeared before the House Un-American Activities Community in 1955, refused to invoke his Fifth Amendment rights (or discuss his very public involvement in the Communist Party of the United States of America), and was blacklisted for his troubles. He’s led the way in the clean-up of the Hudson River.

He is Pete Seeger.

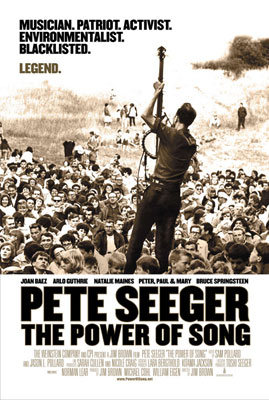

And he is the subject of an excellent new documentary titled Pete Seeger: The Power of Song. Directed by Jim Brown (who also helmed the 1982 must-see The Weavers: Wasn’t That a Time), the film is an inspiring overview of Seeger’s legendary career bolstered by interviews with Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Joan Baez, Mary Travers, Peter Yarrow, Arlo Guthrie and many other cultural luminaries. It also, predictably, has one of the better soundtracks you’re likely to hear this year.

When you’re offered the opportunity to interview the man who wrote "Turn, Turn, Turn", "Where Have All the Flowers Gone", "If I Had a Hammer" and countless other folk anthems, you leap at it. And you try not to gush or tear up or sheepishly ask whether he really tried to axe the wires during Dylan’s live set at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival set. And when you do, you’re glad he laughs it off as apocryphal.

Pete Seeger is a lifelong hero of mine. This is our conversation. I hope you enjoy it. And I sincerely hope you see the film (which is currently playing in New York City and will open in Los Angeles on November 9th, 2007).

Q: What was the impetus for this documentary?

Pete Seeger: I’m a little embarrassed by it, but Jim Brown is somebody I’ve known ever since he was a teenager. He made a very, very good movie about The Weavers about thirty years ago, the quartet that recorded "Good Night, Irene" way back in 1950. So I let him make this movie about me. But I am a little embarrassed because it doesn’t tell any of the stupid things I’ve done in my life.

Q: It’s too kind, you think?

Seeger: Yes. On the other hand, it does have some good music in it. I’m glad you can hear folks singing these old songs.

Q: You mentioned The Weavers: Wasn’t That a Time. In that film, you were sharing the spotlight. Here, you are at the center.

Seeger: At age eight-eight.

Q: I’m amazed by your liveliness. And your voice still sounds like it did on those records my mom played for me as a child.

Seeger: (Laughter) I’ll be darned. Well, I’m fortunate to live in the country, where I have to do a fair amount of physical work just to keep going: raking the leaves, shoveling the ditches and splitting the firewood.

Q: Jim Brown has done a number of folk music documentaries, and you’ve been on camera for him numerous times. But now he gets to talk to your extended family, and you get to see them all discuss your life, your music, your convictions and so on. What was that like?

Seeger: It’s probably good to have pictures. I’ve tried to write about these things with just words, and words can mean different things to different people. And I’ve told a lot of people that the human race won’t be here unless we use all the different means of communication that are possible, whether it’s pictures or music or food or dancing… as well as words. One of the songs I sing almost all the time – whether I’m singing for kids in third grade or senior citizens – is called "English is Crazy". (Reciting and tapping the rhythm) "What other language do you drive on a parkway and park on a driveway? Recite at a play and play at a recital? Have noses that run and feet that smell? And if a vegetarian eats vegetables, what does a humanitarian eat?" (Laughs)

Q: Have you perceived much of a change in your audience?

Seeger: Well, I’ve sung for a wide variety of people. It’s almost a basic philosophy of mine: people say "How do you make a living at this?" I say, "I sing for everybody. Conservatives, radicals, old people, young people, sentimental people, hard-boiled people." And you’ll learn from every different kind of person you sing for by the different reactions you get. I also urge people to communicate with those that they disagree with. If I meet some radical youngster, I say, "Don’t forget to sing for conservatives."

Q: I like how, in the documentary, you say that if you could get two people of different political persuasions in a room together, talking to each other, that they’d find a common ground. My only problem with this is that when two people harboring two very extreme points-of-view get together, they tend to talk past each other.

Seeger: Yeah. That’s right. It’s very easy to say a common phrase that gets misunderstood.

Q: "Misunderstood" is a good word. Your son says at the beginning of the documentary that yours is a "misunderstood patriotism". You were interested in and joined the communist party for a while, and you were always on the extreme left side of most issues. As the country got a little more conservative after World War II, those ideas became anathema. And you were persecuted for those beliefs.

Seeger: I’ve always been aware that musicians could be under attack. Plato is supposed to have written, "It’s very dangerous to allow the wrong kind of music in the republic." And I’m told there’s an old Arab proverb that goes "When the king puts the poet on his payroll, he cuts off the tongue of the poet." I think of this whenever I get a job on TV. Or radio, for that matter.

As a teenager, I was of two minds about pop music. Lots of the songs were very clever, but they were obviously meant to try to cheer up people in this horrible thing called "The Great Depression". I remember singing with my ukulele and getting my school friends to sing along with me:

(Singing and tapping the rhythm)

"He’s just a sentimental gentleman from Georgia, Georgia.

Gentle to the ladies all the time.

And when it comes to lovin’, he’s a real professor. Yes, sir!

Just a Mason-Dixon valentine.

Oh, see them Georgia peaches hanging around him now.

‘Cause what that baby teaches nobody else knows how.

He’s just a sentimental gentleman from Georgia, Georgia.

Gentle to the ladies all the time."

Q: And those songs do serve their purpose, but there is a galvanizing effect that music can have, one that you really helped to exploit. Again, as a young man, listening to your songs, and singing "Turn, Turn, Turn" or "We Shall Overcome" for myself… the power of those songs would invigorate you and make you believe that pretty much anything is possible.

Seeger: It can give you hope in an otherwise seemingly hopeless situation. And this is the extraordinary experience of Africans in America, making up songs while they’re out in the cotton fields. Lots of times, they’d take a tune from Europe; they might be listening at the window of the big planter’s mansion, and there’s a dance going on. They’re playing the Irish fiddle tune. (Pounds out and phrases the melody.) And the next day out in the cotton field, he remembers the tune and slows it down. "Rock-a my soul in the bosom of Abraham, Rock-a my soul in the bosom of Abraham." And so on. (Laughs) I had a song I used to sing back in World War II: (same tune) "No more… business as usual! No more… business as usual!"

Q: I’m not sure many people realize you served in World War II.

Seeger: I was in the Army for three-and-a-half years.

Q: You were there with your banjo and ended up singing for the troops?

Q: You were there with your banjo and ended up singing for the troops?

Seeger: I started out learning how to repair B-24 Bombers, but I got switched to what they call a "Special Service Outfit". I ended up on the Island of Saipan in the Western Pacific, putting together shows for hospitals. There were thousands of wounded coming in from Iwo Jima and Okinawa, and I’d bounce around the island in a jeep putting up a mimeographed poster on bulletin boards saying, "If you can make music or entertain in any way, call this number. There are thousands of guys who could stand some cheering up." I booked string bands, gospel quartets, jazz combos and so on.

Oh, I remember once booking a group of local people. They were islanders from the Marshall Islands, and they had stick dances you’d have to see to believe. Big clubs like huge baseball bats! And sixteen of them would dance a vigorous dance whacking their clubs against each other. I said, "How are these dances used? For weddings and parties?" "Oh, no! Before we go into battle!" (Laughs)

Q: While we’re talking about World War II, I’d like to go back to your comment about how you’re embarrassed that this film doesn’t show what you consider the stupid things you did in your life. You were at one time opposed to FDR.

Seeger: Oh, at one time I thought he was all wrong. And I still think he was wrong in some places.

Q: Over his lack of support for the workers?

Seeger: It wasn’t as simple as that. In many ways, he made some very wise decisions, like the bank moratorium when he first took office, to give people confidence that they wouldn’t lose their savings if the banks failed. On the other hand, he supported Somoza, who had been running Nicaragua like a dictator for decades. [Roosevelt’s] Secretary of State, Sumner Welles, once said "Somoza’s a bastard!" And Roosevelt replied, "Yes, but he’s our bastard." I think this is one of the biggest mistakes of the United States of America throughout the last century: trying to control Latin America. We got cheap products from them, and it was a way to sell our products down there. But they didn’t get real democracy largely because of the United States.

I’m very active these days in trying to get the Congress to pass a bill stopping what they call The School of the Americas at Fort Bening. I’m a very strong supporter of a Catholic priest named Father Roy Bourgeois. About twenty-six or twenty-seven years ago, a friend of his, a Catholic nun, was assassinated in Bolivia. He went down to try and find how it happened, and found she was assassinated by a graduate of the School of the Americas in Fort Bening, Georgia. A year later, he was in El Salvador when Archbishop Romero had made a speech saying that people should be allowed for whoever they want to vote for without being in fear of assassination or massacre. Then Archbishop Romero was assassinated, and, again, one of his assassins was a graduate of The School of the Americas. So Father Bourgeois goes to Fort Bening and gets a copy of the manual; they’re being taught how to assassinate, how to torture, how to massacre whole villages. The polite term for it is "counterinsurgency". If the peasants are getting angry and want to get a more democratic country, you put them down. This had been going on for fifty years or more, and a thousand students a year had trained there at Fort Bening.

So Father Roy started a silent vigil. Then, later on, it became a singing vigil, And it goes on every November on the anniversary of Archbishop Romero’s assassination. It grew from a few dozen to a few hundred to a thousand to a few thousand. When my wife and I were down there – and we went three times – it was 5,000 people. The next year it was 10,000 people. But my wife’s health is not too good now; we haven’t been for three or four years. One year ago, it was 28,000 people – simply standing, listening to a few prayers and speeches, and joining in on songs for two days. And on each of these two days, Father Roy, or one of his assistants, says to the crowd, "Please repeat after me: I will carry no weapon of any sort on me. I will not shout insulting words at the police." And after about ten or fifteen nonviolent pledges, there is a very important one: "If I cannot agree with these pledges of nonviolence, I will disassociate myself from the demonstration." So they’ve been able to keep it peaceful. And if some paid provocateur tries to start something around him or her, say, "Hey, didn’t you make that pledge? Quit what you’re doing."

I am now convinced that if there is a human race in a hundred years, it’s going to be what the future centuries would call "The Great Nonviolent Revolution." The revolution in agriculture took thousands of years; before that, we were hunters and gatherers of food. Then the Industrial Revolution took hundreds of years. But the Information Revolution is only taking a few decades, and if we use it correctly, there will be a Nonviolent Revolution. Of course, this is what Dr. [Martin Luther] King was in for, and one of my best songs is about Dr. King. I made it up right after the Twin Towers were bombed, and I sing it for young and old wherever I go.

Q: What’s the title of the song?

Seeger: "Take it from Dr. King." It has a very syncopated chorus.

(Singing and tapping)

"Don’t say it can’t be done.

The battle’s just begun.

Take it from Dr. King,

You, too, can learn to sing,

So drop the gun."

Then I go into another verse:

"Songs, songs, songs kept him going and going.

They didn’t realize the millions of seeds they were sowing.

They were singing in marches, even singing in jail.

Songs gave them the courage to believe they would not fail.

Don’t say it can’t be done

The battle’s just begun

Take it from Dr. King

You too can learn to sing

So drop the gun."

Q: How do you feel when you hear other musicians interpreting your songs in various ways, like Bruce Springsteen recently did?

Seeger: It’s a great honor. No two people sing songs alike. If he gets the crowd singing with him, that’s the important thing. Participation… if the human race recovers the importance of participation. You see, we did participate years ago when we lived in the small villages. Anthropologists call that style of living "Tribal Communism". If the hunter shot a deer, it was shared; there’s no such thing as one person being rich, and another person being poor. If there was hunger, everybody was hungry, even the chief and the chief’s wife and children. They sang all the time. They sang when they were on hunting parties, they sang when they were pounding corn together. They sang at meal time, perhaps.

Oh, you’d be interested… today in South Africa, when a couple gets married, the friends of the bride form a chorus and the friends of the groom form a chorus, and there are two days of singing. It’s not a two-hour celebration; it’s a two-day celebration!

Q: You know, with my generation and the younger generation today, there’s a real self-consciousness, an embarrassment to sing and feel and participate. They would rather keep a skeptical distance, I guess.

Seeger: I suppose so. On the other hand, you learn a lot from participating, and not just from music. I think participation in politics is important no matter what you opinion is. Swap ideas, and talk about the pros and cons of this and that. The good and bad are all tangled up in this world. You know, we started cleaning up the Hudson almost forty years ago, and, now, what’s happening is that the Hudson Valley is doubling in population every twenty years. I was arguing with a local politician. I said, "We’ve got to slow down." He said, "No, Pete, if you don’t grow, you die." I didn’t have an answer for him then, but at one o’clock in the morning, I woke up and said, "If it’s true that if you don’t grow, you die, isn’t it also true that the quicker we grow, the sooner we die?" I think the world is only so big. We’ve got to find a way to level off and stabilize things.

Q: I recently saw the new Bob Dylan biopic, I’m Not There, and they have a scene in which an incensed Newport Folk Festival organizer – they don’t name names – gets upset about Dylan going electric at the ’65 festival and tries to cut his amplifier wires with an axe.

Seeger: (Laughs) That’s the way someone told the story, but it’s not true.

Q: You’ve refuted this story for years, and yet it still sticks. Why?

Seeger: Because I don’t normally use electrical instruments when I play, although many of my friends do. The sound was so bad, you could not hear one word of what Bob was singing. And it was a good song: "Maggie’s Farm". And I ran over to the sound man and said, "Fix the sound so you can understand the words!" And they had it blasting, absolutely blasting; you could not hear a single word. And the sound man shouted back, "No, this is the way they want it!" And I said, "Damn it, if I had an axe, I’d cut the cables!" But I didn’t have one with me. Probably lucky I didn’t.

Q: Do you think that was Bob’s youthful defiance–

Seeger: Perhaps, yes. Bob is the most independent guy in the world, and he didn’t want anybody – left or right or upside-down – to tell him what to sing. And this was an experiment for him, as much of his life has been a series of experiments.

Q: But many of the other popular acts of that era – Peter, Paul & Mary, Ian & Sylva, Joan Baez and so on – pretty much stayed true to the acoustic sound. I kind of see that as a tribute to your commitment to the music. Do you see it like that?

Seeger: I know what I can do, and I usually try to stick with it. But I’m experimenting all the time. One of my better songs was made up ten years ago for a demonstration to keep the community gardens in New York from being bulldozed and auctioned off for developers. We had a rally for a couple thousand people on Sixth Avenue and 42nd Street in Manhattan, with traffic all around. And I had new words to a beautiful two-part melody in Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony. It’s a famous two-part melody. And I had the emcee ask, "Are there any women who can read music on site?" Because that morning I’d gotten a magic marker and written out the alto part and the soprano part. And I got three altos and three sopranos; they rehearsed it, and, an hour later, I stood between them and said, "One, two, sing!" They sang, I just went oompa-oompa on the guitar, and Beethoven’s Seventh just floated out over the New York City traffic. It was wonderful. (Laughs)

Q: Do you think another widespread folk revival is possible?

Seeger: I don’t think there’s ever been a folk revival that’s widespread, and I don’t particularly want to see it. It inches up in different ways and different places. Some people like to sing gospel songs: those are folk songs. Some people like to sing rhythm-and-blues with lots of metal (laughs), and that’s kind of folk music, too. Some people like Irish songs. In fact, you’d be amused, the tune for "Where Have All the Flowers Gone" I got from an Irish lumberjack song sung seventy or eighty years ago by some guy in the Adirondacks. "Johnson says he’ll load more hay/Says he’ll load ten times a day." I didn’t even slow it down. (Laughs)

Q: Recently, you felt moved to compose a song excoriating Joseph Stalin called "Big Joe Blues".

Q: Recently, you felt moved to compose a song excoriating Joseph Stalin called "Big Joe Blues".

Seeger: Oh, that was just a foolish idea. Somebody asked me "What songs do you think Woody Guthrie would’ve written if he’d been able to write songs in 1956 when Khrushchev made his speech about Stalin?" I just improvised. Guthrie wrote not hundreds, but thousands of songs. And more often than not, he’d put new words to an old tune. So I said, "Maybe he would’ve made up a ‘Yodeling Blues’ called ‘Big Joe Blues’." It’d go, "I’m not talking ’bout middle-aged Joe who wanted to become a new dictator, but he was just small potatoes. I’m not talking about my nephew Little Joe; he’s still going to school, but he still likes to break all the rules. I’m talking about Old Joe. Big Joe." But I’ve never sung that in public, nor do I expect to. It’s not a great song. Actually, not all of Woody’s songs are great, needless to say. He made up a new one every six hours. (Laughs)

Q: I think it’s great how so many of your songs have endured, and can be applied to various situations. "Bring ‘Em Home" ends this film, and, again, it’s sadly relevant. Having witnessed the folly of Vietnam and watched as we went and did something very similar, I’m wondering what your thoughts are on that?

Seeger: Well, in the first place, I think getting out of Vietnam was one of the great victories for the American people. We snuck into it almost without knowing; Eisenhower is supposed to have said, "We need tungsten, and only China and Vietnam have tungsten". At that time, we weren’t even talking to China; it took Nixon to open that up. The Vietnamese Communists looked like they were going to take over the country again because they’d driven the French out. So the next thing you know, there was a puppet in charge of Saigon, and most of the Vietnamese people didn’t think much of him. So then we got another puppet and another puppet, and, before long, we found ourselves deep in an undeclared war. At first, people think, "Well, your country’s at war, you’ve got to support your country." But as the truth came out, the country turned against it. And it took a whole generation of young people to get us out.

Q: Once again, we’re trying to do the same thing, but the approach is different. There are people out in the streets, but not in the numbers seen during Vietnam.

Seeger: Oh, I’m convinced that if there is a human race here in 100 years, it’s not going to be big things that do it; it’s going to be millions upon millions of small things. Have you read a book called Blessed Unrest? It’s written by Paul Hawken.

Q: I know of it, but I haven’t read it.

Seeger: He’s spoken at, like, a thousand places over the last fifteen years, and he finally comes out with a book boiling down his opinion. The subtitle of this book is "How the Largest Movement in the World Came into Being and Why No One Saw It Coming". What is this movement? It does not have a name, and will not have a name. These are peaceniks, econiks, civil rights-types, people who say "Stop this!", "Save that!". And they’re all working pretty much locally. One of the bigger little groups is Clearwater, which is trying to clean up the Hudson River. It’s halfway clean now; we’re swimming in it again. It’s still not safe to eat all the fish: the little ones aren’t too bad, but the big ones still have a lot of chemical in them – which was put in them by General Electric. They don’t want to spend the money to clean it up because it’s very expensive.

Q: Of course!

Seeger: They have modern dredging devices, which are not like the old ones that just scooped out the muck. They’re more like a vacuum cleaner, and they do it in a control situation so they don’t stir up the muck, they just suck the PCBs off the surface.

Oh! You know what happened? Just two weeks ago, nine people from Greenland came down to visit us because they say they’re getting PCB in their food; the seals that live in the Arctic are eating the fish which, after they’ve gotten PCB in them in the Hudson, are now swimming north. They get eaten by the seals. And every time you step up another link in the biological chain, you get a higher concentration of PCB. So a little fish might have one part per million, and the Striped Bass have got forty parts per million. They’ve found the snapping turtles have a thousand parts per million. Now, the seals are the main food supply of Greenlanders: there aren’t many of them up there; in all of Greenland, there are fifty-six thousand people. They live in little settlements, a hundred here and 200 there – mostly on the west coast, and a few on the east coast. Most of the island is a great big hunk of ice: two miles thick at the top. But it’s melting. Slowly, but steadily. If all the ice in Greenland, the ocean would be twenty-three feet higher. The Dutch are already building their dikes eighteen-feet higher. It’s going to be a worldwide tragedy for people on islands; they’re going to have to move somewhere else? Where’s Bangladesh going to go?

The bad and the good are all tangled up in this world. On the other hand, I think it may be the wake-up call the whole human race needs. We’ve got to start working together, folks. Or else there won’t be any human race here.

Pete Seeger did pretty well by the human race in the twentieth century. It’s probably not a bad idea to pay him heed for another 100 years. At least.

Again, Pete Seeger: The Power of Song opens at the Laemmle’s Music Hall 3 in Beverly Hills on November 9th. See it.