The quickest way to go broke in Hollywood is to fret about artistic integrity. Conversely, the quickest way to lose one’s voice is to compromise. But without compromise, there is no tending to one’s artistic integrity; therefore, the only way to truly succeed in this business is to adulterate one’s voice to ensure maximum accessibility. But what’s accessible for a mass audience is alienating for the artist. Success distances, makes it harder to connect, and, finally, renders the art either impotent or obscure.

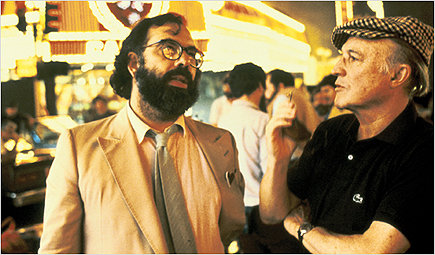

It’s beginning to sound like Francis Ford Coppola has finally embraced obscurity with his forthcoming "experimental" feature, Youth Without Youth (third-party reactions are an unfortunate necessity as CHUD was thoughtfully excluded from the recent press junket). It also doesn’t sound like he’s terribly happy about it. This morning, the New York Daily News‘ gossips, Rush and Molloy, hot to touch off a Clash of the 1970s Cinema Titans, excerpted a series of seeming disses fired off by Coppola (in the November issue of GQ) at three of his most legendary – and, currently, more financially successful – ex-collaborators.

"I met both Pacino and De Niro when they were really on the come," Coppola tells GQ‘s Nate Penn. "They were young and insecure. Now Pacino is very rich, maybe because he never spends any money; he just puts it in his mattress. De Niro was deeply inspired by (Coppola’s studio American) Zoetrope and created an empire and is wealthy and powerful.

"Nicholson was – when I met him and worked with him – he was always kind of a joker. He’s got a little bit of a mean streak. He’s intelligent, always wired in with the big guys and the big bosses of the studios.

"I don’t know what any of them want anymore. I don’t know that they want the same things. Pacino always wanted to do theater … (He) will say, ‘Oh, I was raised next to a furnace in New York, and I’m never going to go to L.A.,’ but they all live off the fat of the land."

Taken out of context, this smacks of hypocrisy: after all, where does the director of Jack get off criticizing anyone’s creative torpidity? Checking in with the gossip remora, the hilariously biting reaction to Coppola’s intemperance can be summarized thusly: "I’m sorry… Francis Ford Who? He’s still alive??? At least Pacino and De Niro and Nicholson have made a good movie or two over the last ten years. What’s Coppola done? The Rainmaker? More like Law & Order Lite. L-O-Motherfucking-L! Why doesn’t this fat jerk just shut up and get back to hawking overpriced wine and enabling the solipsistic follies of his children? He hasn’t mattered since Apocalypse Now, anyhow, and he forever ruined that non-masterpiece with Redux. By the way, The Godfather movies have aged horribly, and The Conversation is one big artsy-fartsy wank. His only great movie is The Rain People."

There’s no denying Coppola lost his way in the 1980s and 90s, but making movies to get out from under a mountain of debt has a way of throttling the muse. Yes, Jack is noxious. Undoubtedly, Bram Stoker’s Dracula is two hours of opulent art design and dreadful acting. But there’s a lot to love in The Rainmaker and Tucker: The Man and His Dream, and it’s not like Gardens of Stone is a complete embarrassment. There’s no reason to believe Coppola is completely tapped out creatively.

But the man who exploded the possibilities of the medium in the 1970s is never coming back. And no one’s more aware of this than Coppola. For anyone who cares to understand the source of the (rather mild) bitterness directed at Pacino, De Niro and Nicholson, here’s a comment from earlier in the GQ interview: "In fact, after Godfather II, nobody wanted to be involved with me on Apocalypse Now. Not the studios to help finance it nor any of my friends to act in it. Bobby De Niro, Al Pacino – nobody wanted to work on it with me. I thought, God, I made all these movies and I won all these Oscars, and still I can’t do the movies I want to do."

Now, the internal battles waged during the grueling production of Apocalypse Now would’ve occurred regardless of who played Kurtz; however, what Coppola seems to be getting at is the fact that his key collaborators, the ones he turned into movie stars, deserted him when he needed them most. Coppola’s business model for Zoetrope may have been deeply fucked, but who’s to say he wouldn’t have, with a little movie star insurance, secured the requisite financing to achieve the "live cinema" effect he dreamt of for One from the Heart? And, beyond that, who’s to say the hypothetical success of a fully realized One from the Heart wouldn’t have kept the wolves from the door long enough to give Coppola a less financially crippling exit out of that doomed scenario?

Unfortunately, Frederic Forrest was no one’s idea of a movie star then or now, and One from the Heart died an ignominious death. While the popular theory regarding Coppola’s abrupt artistic decline holds that Apocalypse Now burned him out, this is demonstrably false. The musical broke his heart. His dreams of an artist-friendly studio were ground up before they ever had a chance to take root (watch the supplements on the One from the Heart DVD for a painful glimpse at what might’ve been). And no one should have to suffer through the death of a child as Coppola did in 1986, when his oldest, Gian-Carlo, was killed in a boating accident.

Creating is painful enough, particularly when any form of acceptance is repeatedly denied. So when an artist like Coppola sidelines himself for an entire decade in an effort to "reinvent the language of cinema" with an epic like Megalopolis while his contemporaries become millionaires off of dross like Showtime, The Recruit and Something’s Gotta Give, there’s going to be bitterness. And it’s going to be earned.

According to Coppola, Megalopolis "brought me to my knees". He also admits, "It was clearly beyond the limit of my capabilities." It may be hard to grieve for an artist who’s able to cobble together $17 million for what he’s termed a "student film", but these are still awful epiphanies. Francis Ford Coppola fretted about artistic integrity too much, compromised too late, and, in the process, lost his voice entirely. E.M. Forester made it sound so easy. "Only connect." Why bother when no one wants to connect to anything save for their own imagined genius anymore?

But Coppola’s still out there, trying to speak to something while no one is listening.