FF #1 (Marvel, $2.99)

By Adam Prosser

I haven’t been reading many Marvel comics lately, and I’m actually not sure why that is. I am, historically, a DC guy, but I’m not so partisan that I refuse to read the competition, or acknowledge it when it’s better. And right now Marvel is definitely putting out the better work of the “big two” superhero publishers, if only by default. While DC has been displaying its contempt for both creatives and readers with its pandering, tired, poorly-conceived gimmick series, Marvel’s been going through a minor creative renaissance, hiring some of the more innovative and talented creators and allowing them to push things in rather unique directions on several books. This has been epitomized by Jonathan Hickman’s reworking of the Fantastic Four into the Future Foundation. A concept that could easily have been a silly gimmick or a “shakeup” that reverted to the status quo a year later, the Foundation was instead rooted in a well-thought-out philosophy and Hickman’s distinctive point of view, and as such, has provided some of the most fresh and exciting FF books since the days when Stan and Jack were making them. It’s not a coincidence that even with Marvel Now! offering the temptation to reboot and strip away continuity, Hickman’s vision of the FF is continuing onwards with a new writer and a separate book (also providing a convenient way for Marvel to double up on the franchise, but it’s done elegantly and organically enough that I’ll say no more about it.)

FF #1, like Fantastic Four, is being written by Matt Fraction, so the two should complement each other elegantly. With the classic FF about to leave Earth for a journey through space and time, Reed Richards has decided to appoint a new FF to keep their interests, particularly the Foundation and that whole “defense of Earth” thing, going in their absence. Of course, Reed’s intention is only to be gone for four minutes (from the perspective of those left behind; subjectively, the trip will seem like a year), but of course, the chances that it’ll actually work out that way are pretty slim, so the backup team makes sense. The oddball assemblage consists of Ant Man (Fraction’s smart enough to use Scott Lang and not Hank Pym, the latter being a character I think is now irreparably broken), She-Hulk, Medusa, and a new character, Darla Deering, aka Miss Thing (who will apparently be wearing a battle suit modelled on Ben Grimm’s rocky hide, though she doesn’t in this issue).

While I don’t think Fraction’s some kind of infallible wizard (even here, he slips in some of the typical continuity-based angst—Lang recently lost his daughter, Cassie, aka Stature of the Young Avengers—that I find so tiresome in modern superhero comics), he can be really great. He certainly has a tremendous understanding of how to structure a first issue—it cuts between rounding up the team and a series of introductory speeches by the inductees of the Foundation, mostly children, that introduces them efficiently and effectively. Fraction also knows how to use the promise of more as a tantalizing hook instead of a desperate delaying tactic; even though the story’s just getting started by the end of this issue, you don’t feel cheated. Heck, there’s no real action and barely even any conflict here, and yet I was left eager for more.

As effective as Fraction is, though, the real draw for many will be Mike and Laura Allred, for whom no introduction is needed at this point. Their quirky, retro style—oddly stiff, but in a somehow charming way—conveys more character with a few clear lines and flat colours than any three more typical modern superhero artists could do. Jack Kirby once responded to the host of imitators he’d spawned by saying that, if people really wanted to be true to his artistic philosophy, they’d do something new. The Allreds seem to embody what the King was talking about: without being imitative of Kirby’s style, they’ve evoked his spirit, and that of the great Silver Age comics in general.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Clone #1 ($2.99, Image/Skybound)

Clone #1 ($2.99, Image/Skybound)by D.S. Randlett (@dsrandlett)

There have been a lot of science fiction comics coming out probably since Brian K. Vaughn, Pia Guerra and friends gave us Y: The Last Man. Y was a seminal series (no pun intended) for its ability to get right what writers in serial media of all kinds typically get wrong: the long running feeling of mystery and revelation. What also made that series a landmark, and what makes Vaughn a very good science fiction writer, was Vaughn’s ability to ground his high concepts and breakneck pop storytelling on a foundation of humanity. Vaughn is definitely a “pop” author, but it’s also obvious that he reads books that deviate from the standard pop culture paradigm, which lends his work a more literary and humane sensibility than many of his contemporaries.

Unfortunately, his imitators have learned all of the wrong lessons from the success of Y and Saga. Where Clone goes wrong isn’t its high concept, but in its thinking that that high concept is enough. After the story ends, there’s a brief afterword by the book’s writer, David Schulner. It shows that he’s a much better writer and that he has more on his mind than the actual comic lets on. After reading this brief block of text, I was a little bit baffled, and a little bit pissed off. The ideas that he cited as important to him for this story were actually compelling (What if you met another you, but that other you isn’t who you think you are?), but they are barely present in the story itself.

I understand that this is a first issue, and first issues typically serve as an introduction to characters and plot, and to serve up some sort of hook. The only hook that Schulman presents us with is a dull narrative one when his concept is capable of supporting thematic hooks that cut deeper and go to some more unsettling places. But we just end up with a high concept Bourne knock off.

Which is a shame, as there’s a lot of talent in this book. Juan Jose Ryp has been around for a while now with his Geoff Darrow-esque style. He doesn’t skew toward humor as much as Darrow does, and his faces aren’t quite as expressive, but his lines feel very similar, and he’s every bit as adept at capturing movement amidst all of his detail. Here, Ryp feels like a very big gun in the service of a very small child. He makes the story feel urgent and important, but it ultimately doesn’t have the experience and the touch necessary to really hit anything.

Rating: Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Avengers #1 (Marvel, $3.99)

By Jeb D.

The relatively few criticisms of Jonathan Hickman’s run on Fantastic Four centered around the fact that the end of his grand storytelling run seemed to leave the team more or less unchanged by their experiences; quite apart from the corporate necessity of putting all the toys back in the box when you’re done with them, I was actually rather pleased that he left future writers with a few new resources to draw on (the Future Foundation, the time-and-space-hopping extended Richards family), without slapping a lot of gimmicky change-for-its-own-sake on the book. And while I hesitate to draw too many conclusions from a first issue, I get a similar vibe from Hickman’s debut on Avengers: there’s enough foreshadowing and tantalizing hints to suggest that he’s got an epic journey and firm endgame in mind; and the more open-ended nature of what constitutes an “Avenger” will allow him to bring in pretty much any Marvel character that interests him without having to shoehorn them into an existing family structure.

This first issue is an exciting and dramatic opener, though of course it’s only that. Hickman does a fine job of laying out a series of threats of epic scale that he has in store, with roots in the very creation of the universe, while the immediate one is personified by an intriguing set of foes who challenge the now-standard “movie-verse” team. It’s up to the individual reader how they feel about incorporating traits from the films into the comics (would a pre-Chris Evans Cap have called a female supervillain “ma’am”?), but I’ll take it over the need to cram Spidey and Wolverine into the team willy-nilly; the jury’s still out on that, though, since this issue ends with Cap, the only one left standing from their throwdown with Ex Nihilo and company, essentially summoning up every possible permutation of Avengers to take on the threat. I trust Hickman enough to say that, if he brings an “overused” character into the book, he will do it with purpose.

Art-wise, Hickman couldn’t be better served: Jerome Opena gives the book a grandly cinematic feel, without dipping into the obvious “widescreen” playbook. It’s emotionally-charged, inventively laid-out, lovingly detailed, and graphically exciting; Opena also tosses a few tantalizing Easter eggs into the exposition sections.

As is typical for a debut issue, I try to balance my grading between what’s actually contained within the book’s covers, and what expectations are created by the creators’ track records, and what they offer for openers; given that, I’m expecting some great things.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Blackacre #1 (Image, $2.99)

Blackacre #1 (Image, $2.99)

By Adam Prosser

On the first page of Blackacre, writer Duffy Boudreau promises “ZOMBIES VS. PIRATES!!!” It’s a tease, and a rather cheap one, to be honest–the actual comic has nothing to do with this idea, and is in fact a more thoughtful (and debatably more “realistic”) story. Zombies vs. Pirates is just a metaphor for different perspectives on the apocalypse, or more precisely, on the slow undermining of society that we fear may be coming. I can’t decide if Boudreau’s bait-and-switch is a cheap tactic or a ballsy subversion of the typical concerns of comic book geeks.

Either way, the comic that follows is well-executed, with smart dialogue and world-building, but I can’t help but feel it’s lacking something. The same university lecturer who promises us zombies vs. pirates proceeds to fill us in on the history of the coming hundred years, the “new American dark age”, in which the country declines not with a bang but with a whimper. As America’s grasp slackens overseas and eventually within its own borders, A consortium run by a “visionary billionaire” constructs “the mother of all gated communities”, the titular Blackacre, a more plausible version of Judge Dredd’s Mega-City One, as the rest of the country (and the world?) falls into chaos and barbarism. A hundred years later, Blackacre essentially maintains the American way of life, defended by a high-tech military from religious fanatics beyond its walls. One of those military men, Hull, is given a new assignment: to retrieve an agent who’s been undercover among the “barbarians”–except Hull doesn’t realize he’s on a suicide/assassination mission…

I only just realized, reading what I’d written, that Blackacre is very much in the tradition of “Atlas Shrugged”, with wealthy supermen constructing a haven for civilization while the rest of the world becomes a band of ravenous pirates and superstitious savages. I can’t help but notice that Boudreau seems to think the world will be ending due to stuff like the debt crisis and turmoil in the middle east, not to mention the “fall of America as a superpower”–you know, stuff the newspapers have been trumpeting for decades–rather than far more likely and serious concerns like possible ecological devastation and the attendant resource wars. Yeah, I’m a dyed-in-the-wool granola-munching lefty, what of it? But I don’t think you have to be particularly left-wing to find Ayn Rand’s vision of capitalist ubermeschen “going Galt” and forging a perfect society implausible; there were always a lot of gaps Rand’s explanation of how this new, capitalist society consisting entirely of the 1% was going to work. (As a Bob the Angry Flower strip put it, “What? You guys all forgot to bring an army of indestructable robot labourers?!?”) Fortunately I don’t think Boudreau is making a Randian argument per se–it’s clear Blackacre is no paradise, and there’s a running subplot that’s clearly sympathetic to the “savages” outside the walls. In fact I’m tempted to give this comic points for the relative subtlety of its politics. The flip side of this is that there’s a certain blandness to the scenario, but this is the first issue, after all–the depth of the conspiracy and the villain’s plots (or even who the villain is) has yet to be established.

It’s possible the sense of blandness is partly emanating from the artwork, by Wendell Cavalcanti and Sergio Abad. Sterile and stiff, with rather distorted-looking human faces, this is a decidedly amateurish effort that can’t seem to decide if it’s going for old-fashioned sleekness or modern detail, and as a result falls between two stools. Even the colors are mechanical and flat. I’ve given better reviews to comics with worse art, but that’s usually because there was a sense of amateurish exuberence present; here, there’s an assembly-line feel that makes it seem like an attempt to ape some of Avatar’s lesser offerings. I don’t mean to sound TOO harsh here–Blackacre #1 isn’t really worse than some of the weaker issues of, say, Astro City–but the art really turned me off. Too bad, because the script shows a really impressive level of proficiency.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Thunderbolts #1 (Marvel, $2.99)

By Jeb D.

I sympathize with the Marvel fans who feel that this series has moved too far off the rails from Busiek and Bagley’s original “villains-pretend-they’re-heroes” concept, but over the past few years, the series has made room for effective political commentary, character work, twisty plotting, and black humor from writers like Warren Ellis, Andy Diggle, and Jeff Parker, and a blithe sense that it could go pretty much anywhere, though the artwork could be a tad spotty. The Marvel Now! version suggests a more pared-down concept that, at first read, feels a bit reductive compared to what’s come before.

I presume that this is the book that chased Greg Rucka off his terrific Punisher series, since the arc of this first issue involves Frank Castle being “persuaded” (read: given no real choice) to join “Thunderbolt” Ross’ new self-named black-ops team of super-powered reprobates. Writer Daniel Way’s Ross is a close cousin to Garth Ennis’ Fury, unabashedly embracing the realpolitik involved in assembling an amalgam of the damaged and dangerous (Venom, Deadpool, Elektra, etc.); the issue alternates between Ross laying out Castle’s lack of options (it’s basically join up or die) with flashbacks to his somewhat better-received recruiting trips involving the other members. I’ll say this: while this first issue might appear to close off some of the intriguing possibilities that other writers have brought to this franchise (it’s hard to envision much in the way of convincing grey areas for this bunch), it’s near-perfect as a blueprint for what’s to come.

In addition to slightly resenting this series for sundering Rucka’s relationship with the Punisher, it’s also tough to see the character back in Steve Dillon’s hands and not pine for more of his collaboration with Ennis on the character. Dillon always gives good gore, and having a cast of characters that don’t all have the same nose (given that we have both masked and female characters featured) will add a bit of visual variety. There’s the usual stiffness to some of his paneling and postures, but his aggressively bleak work is certainly appropriate for what Way has set out for him; the question is whether we really need another black-hearted book about psychotic superheroes, even one executed as efficiently as this one.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

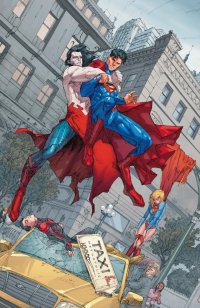

DC’s First Month of H’el

DC’s First Month of H’elby D.S. Randlett (@dsrandlett)

I’ve long suspected that the reason why Superman comics are so frequently bad is that the people who frequently write them have grown up reading only superhero comics and pulp scifi. Or at least, when it’s time for them to write Superman, they act like that’s all they’ve ever read. You would think that that approach would work, as there are other superheroes that it does work for. For example, some of Batman’s best stories are just simply well written and well drawn yarns, and the same can be said of of pretty much any other superhero. I think that this might be because these characters came after Superman, after the superhero genre had been established, whereas Superman draws from earlier literary traditions. If a Superman story has even a hope of being any good, it has to about something. Superman was making (sometimes radical) political statements from the beginning, and he’s long been an effective vehicle for exploring modern emotional struggles from the perspective of heroic fiction. He is the Heracles for post-Enlightenment ideas of self, but he also contains elements of Huck Finn, and is at his best when his titanic feats of strength are married to personal and social sojourns. Even then, it can go wrong, but the truly great Superman stories somehow get a handle on those elements of the character.

The problem with the Superman family line (Which has excluded Morrison and co.’s Action Comics, a title with problems all its own) is that it’s made the mistake of thinking that the idea central to Superman is power. It’s an easy mistake to make, as it’s an obvious surface element, but Kryptonian power and strength has deeper resonances when used as an image of a self that’s completely “on.” That’s not to say that we can’t have fun with Superman’s power and have some big slobberknocker fights, but they have to be earned.

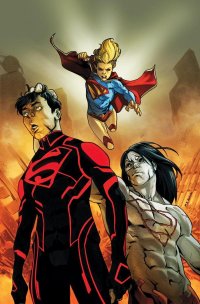

So here comes H’el on Earth, a crossover between the Superman, Superboy, and Supergirl titles. We had a prelude to it a couple of months ago with the pretty much alright debut of Scott Lobdell and Kenneth Rocafort, which set out to set down New 52 Superman’s personality. Really, they needed at least a few more issues to let plots like “Clark quits the Planet!” come to more of a head before launching into H’el on Earth, which kicks off on the last page of the thirteenth issue of Superman, with the reveal of the big villain, H’el, who comes from out of nowhere with no build up. More is revealed about him in Superboy and Supergirl. He’s essentially a dressed up Zod (complete with the psychic powers from Superman 2!) or Bar-El. A Kryptonian exile and adopted member of the El family who flew a test space flight for Jor-El, he became lost in the Universe, eventually discovering his Kryptonian powers plus a few extra. He seeks to resurrect Krypton through some as yet hidden means, but I think we all know how that will turn out.

Supergirl titles. We had a prelude to it a couple of months ago with the pretty much alright debut of Scott Lobdell and Kenneth Rocafort, which set out to set down New 52 Superman’s personality. Really, they needed at least a few more issues to let plots like “Clark quits the Planet!” come to more of a head before launching into H’el on Earth, which kicks off on the last page of the thirteenth issue of Superman, with the reveal of the big villain, H’el, who comes from out of nowhere with no build up. More is revealed about him in Superboy and Supergirl. He’s essentially a dressed up Zod (complete with the psychic powers from Superman 2!) or Bar-El. A Kryptonian exile and adopted member of the El family who flew a test space flight for Jor-El, he became lost in the Universe, eventually discovering his Kryptonian powers plus a few extra. He seeks to resurrect Krypton through some as yet hidden means, but I think we all know how that will turn out.

There’s still some mystery surrounding the character, which is quite the feat considering all of the hasty exposition that’s gone into building him up so far. That’s mainly what the crossover has been so far: H’el beats the shit out of whoever’s title is running that week while spouting off his motivations and origins. The only issue in the crossover where there’s really any forward momentum is Superman #14. From a publishing standpoint, it’s easy to see why: that’s the best selling, marquee title, so you want the big developments to happen there. Supergirl, which is actually a pretty solid title, deals with this industry fact actually rather well with its focus on the main character and her relationships, all in a fairly new reader-friendly way.

Superboy is pretty terrible. I thought that this book was actually off to a pretty strong start last year, but I haven’t kept up with it. There appears to be a new creative team here, and they’re not very good. In terms of this crossover, nothing happens in this issue. Superboy gets taken down by H’el pretty early on, and then the Teen Titans come to lend a hand. They get taken down, but the conflict here has absolutely no relevance to any of the characters present. Even though it’s big superhero stuff that’s happening, it is absolutely boring and meaningless.

Superboy is pretty terrible. I thought that this book was actually off to a pretty strong start last year, but I haven’t kept up with it. There appears to be a new creative team here, and they’re not very good. In terms of this crossover, nothing happens in this issue. Superboy gets taken down by H’el pretty early on, and then the Teen Titans come to lend a hand. They get taken down, but the conflict here has absolutely no relevance to any of the characters present. Even though it’s big superhero stuff that’s happening, it is absolutely boring and meaningless.

Superman #14 is, like the issue before it, frustrating as hell. For every flash of quality or character, there’s a compensating bit of clumsy exposition, or the flow of events is a little too busy resulting in pacing that’s off. I don’t know if that has anything to do with the talent involved, as Rocafort’s art is pretty great, and there are moments that show that Lobdell just might have a grasp on how to write Superman as a character, but the narrative is simply too busy, and so the flaws stick out more than the virtues. I’m pretty sure that the sense of rushed-ness stems from the lack of a cohesive vision in the first year of the main Superman title. They’re trying to pull of a Night of the Owls style event here, but that had the benefit of being grounded on Snyder and Capullo’s vision, which was given half a year to build.

But even if this crossover were paced like Night of the Owls instead of this first month of infodump, would it matter? Possibly, as there is some vision for the principal characters on display, but also a lack of consideration at some of the more traditional, powerful, and core ideas surrounding them. In the end, H’el on Earth and the Superman family titles are interesting to watch because they represent a microcosm of everything that’s wrong and right about the New 52. The old status quo needed to be retired, and there are hints of exciting ideas and stories, but they appear to be getting lost in a larger boondoggle of an editorial board and general creative mindset that can’t resist its past mistakes.