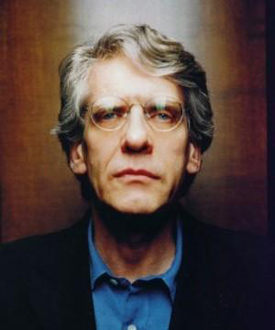

Eight AM on a Sunday morning is not the ideal time to do a phone interview. But I’d been pestering Focus Features for a chance to talk to David Cronenberg since well before the Toronto Fest started, and when they kindly hooked me up with a one on one towards the end of my time there, I wasn’t able to do it because of scheduling problems.

Eight AM on a Sunday morning is not the ideal time to do a phone interview. But I’d been pestering Focus Features for a chance to talk to David Cronenberg since well before the Toronto Fest started, and when they kindly hooked me up with a one on one towards the end of my time there, I wasn’t able to do it because of scheduling problems.

So when Focus called last week and offered this Sunday breakfast interview, I had to say yes. Never mind that we were having a party at my house Saturday night (my birthday party, no less, so I couldn’t well skip it) meaning I’d have to work to stay sober to be up in time for the conversation. As it turned out, the party was done at about five, leaving me three hours to wait out before the call. When he rang at eight, I was stupid and exhausted and he, as it turned out, had a cold.

Therefore, this isn’t quite the ideal conversation with Cronenberg about Eastern Promises, the license of success and torture porn. We only had a few minutes and I could easily have followed up with those three subjects to fill an hour, not to mention all the other topics that come to mind when you’re on the phone with a filmmaker like Cronenberg. Even so, he was in a good mood. You can’t necessarily tell from the transcription, but throughout, Cronenberg was chuckling and joking.

Waiting for your call, I was watching Kirby Dick’s movie This Film Is Not Yet Rated, and that got me wondering if you had problems with the MPAA approving Eastern Promises for an R.

No, it got an R rating very quickly, actually.

Do you think the success of A History Of Violence helped with that? It seems like there could be a bias based on success that could affect the rating.

I don’t really think so, no. I haven’t had a film that gave me some trouble since…well Crash was NC-17, but we understood that. Earlier on Videodrome was one where I had to make some cuts I wasn’t too happy about. But since then I haven’t had a problem at all. With A History of Violence I understand there was a lot of discussion, but you hear that sort of thing second or third hand. With this movie, I don’t know that there was any particular contentious moment, and we submitted it as I wanted it to be and it was accepted.

Have there been other positive effects from the success of History in a general sense? There’s always a public idea that success translates to a license to work with more freedom.

That license does not exist. There is no such thing as a license to do whatever you want. Talk to Marty Scorsese about it, or even Spielberg. Don’t forget, it’s not as if History made two hundred million. It didn’t. I have found that everyone is very pragmatic. There are some crazed moments, but they do read your script. Let’s put it this way, let’s say I’d done History then wanted to do Spider for twenty-five million. I wouldn’t have gotten it made! For example, after I did The Fly, which was a huge hit and my biggest hit when you correct for inflation, I still couldn’t get Dead Ringers made. In other words, people read that [script] and say, gee, why don’t you make something more like The Fly? So it’s not like there’s some magic where everyone is hypnotized by your last success and you can command them to do whatever you want. I wish that could happen, but it never does. People are pretty pragmatic and they can see what a project is.  Now, having said that, I can definitely say that I have gotten phone calls from various things that I would not have had after Spider. There are some things I was interested in after I’d done Spider and studios were not interested in me because they just looked at the last film I did and thought it was too weird, too obscure, too uncommercial. So after History, those people would now return my phone calls, and that’s something. It’s true, I’m in my ‘hot’ ten minutes right now. We’ll see what happens in the next ten minutes! So it has made a bit of a difference, definitely.

Now, having said that, I can definitely say that I have gotten phone calls from various things that I would not have had after Spider. There are some things I was interested in after I’d done Spider and studios were not interested in me because they just looked at the last film I did and thought it was too weird, too obscure, too uncommercial. So after History, those people would now return my phone calls, and that’s something. It’s true, I’m in my ‘hot’ ten minutes right now. We’ll see what happens in the next ten minutes! So it has made a bit of a difference, definitely.

I understand that the Eastern Promises script is significantly different now from what it was when you received it. Can you hit on the most crucial differences?

Well, unfortunately to do that, I’d have to give a lot of the movie away. The ending was totally different.

But in general, I’ll just say that it was definitely a first draft that had never got a chance to be evolved, and Steve was really excited to get me involved, because most studios or producers don’t want to spend money on a script unless there’s a director involved. That script had languished at BBC Films for some years, and Steve was excited to have a collaborator; there was no ego involved. As a first draft, he had maybe gone off in five different directions at once, because there are various possibilities and he sort of tried them out all at once in the script. I was able to say, no, reading this objectively I can see that this is the way to go and not that way.

[There’s some conversation in between here that he wanted off the record, so we end up jumping to a vague discussion of the ending of Eastern Promises…]

I think that Steve has a tendency to fall in love with his characters, and then he has difficulty hurting them. That happened in Dirty Pretty Things, he wanted them to be happy ever after. I don’t have that problem. I’m happy to hurt them. I felt then, that this is kind of a half-happy ending. It’s a mixed ending, sort of bittersweet for Anna and Nikolai. It’s an ambiguous ending that way, which to me is kind of the way it works in life. I don’t really think that I’m imposing a pessimism or a negativity on my films…I think my films are pretty realistic that way. It’s rare that we score a total victory in our lives, so I think this is accessible but realistic.

So the ending that was might have been too easy…

Yes, and it depends on your approach as a filmmaker. There was a time when, for example, poetry was meant to present a beautiful, ideal world. If presenting is something idealistic and comforting is your approach to filmmaking and you’re not looking for hard realism or a realistic reflection of life as it’s lived, you’re looking for life as we wish it were. I don’t think that’s a bad approach at all, it’s just not my approach.

There’s a reveal in the film which some audiences see as a twist, but I got the sense that wasn’t the tactic you were trying to employ.

Well, I’ve had all kinds of responses. I’ve had people say they didn’t see it coming, but it’s not presented as a massive ‘oh my god!’ kind of twist. In a way it’s set up rather well. You begin to see that this man is more tender or sensitive than you would expect from a guy like that. So from his character as it is, it’s not a total shock. Nothing in the story is presented as the twist of all twists, by any means, it just rolls along. Some people are surprised by it, some people aren’t, and either way it’s OK with me. If I’d presented it as…well, if it were like the revelation at the end of The Crying Game and it didn’t work, then yes, that would be bad and would mean the movie didn’t work. But it just rolls along, in the sense that everybody in the movie has secrets, everybody is guarding something, everyone is trying to manipulate everyone else, including Anna and this is just more of that.

A twist like that in The Crying Game doesn’t seem like a storytelling tactic you’ve ever been interested in.

It’s because it beomces a one-trick pony. It becomes a joke with a punchline. If you’re after more complex things, then that’s a completely different structure and approach to what you’re doing. I don’t want to be boring, and I don’t want to be totally predicatable. But I am working, in this film in particular, within a genre, which is crime/gangster. And playing with genre there are conventions, people come to it with expectations and you want them to have those because it gives you some strength and some structure but at the same time if you only follow the conventions like A, B, C, D you’re predictable and boring. So you have to confound expectations rather than just satisfying every one of them.

It’s because it beomces a one-trick pony. It becomes a joke with a punchline. If you’re after more complex things, then that’s a completely different structure and approach to what you’re doing. I don’t want to be boring, and I don’t want to be totally predicatable. But I am working, in this film in particular, within a genre, which is crime/gangster. And playing with genre there are conventions, people come to it with expectations and you want them to have those because it gives you some strength and some structure but at the same time if you only follow the conventions like A, B, C, D you’re predictable and boring. So you have to confound expectations rather than just satisfying every one of them.

I’m curious to hear your take on the term ‘torture porn’, which has become a popular tag of late.

It’s interesting, since I alluded to it in Videodrome almost thirty years ago with a TV show presenting torture as entertainment. But I haven’t seen these films, Saw and Hostel, so I’m speaking out of a certain ignorance, please let people know that. But I think people see horror to confront fears in a safe way, and we are living in a very strange time when you can see snuff porn on your computer any time of the day or night in the comfort of your home. So if you want beheadings, throat cuttings, people being stoned to death, you can see it for real. That is being used for political propaganda, but also for North Americans, who are confronting seeing soldiers and citizens being beheaded you could make a case for that having something to do with the success of these movies. It’s just a theory, of course, but I think it’s a solid one.

I know you have to run — quickly, can you comment on the rumors that you might be involved with HBO’s show Preacher?

Yeah, I have no idea where that comes from, it’s a complete falsity. I’ve never seen it, I haven’t been approached about it, I don’t know anything about it.