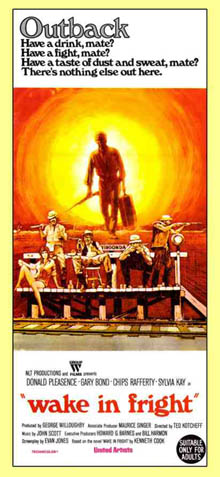

One of the centerpieces of this year’s Fantastic Fest was a screening of a little Australian film from the 1970s called Wake in Fright. Directed by Ted Kotcheff (First Blood, North Dallas Forty) and based on Kenneth Cook’s 1961 novel of the same name, the film follows John Grant (Gary Bond), a disgruntled intellectual from the big city who is unhappy with his teaching job in a Podunk town. On his way back to Sydney during a school-year break, Grant becomes stuck in an Outback community, Bundanyabba (known as “The Yabba”). The men of The Yabba are a hedonistic lot, who like drinking, wrestling, gambling, and shooting kangaroos. Despite the condescension with which Grant views these men, he finds himself pulled further and further into the Yabba way of life.

One of the centerpieces of this year’s Fantastic Fest was a screening of a little Australian film from the 1970s called Wake in Fright. Directed by Ted Kotcheff (First Blood, North Dallas Forty) and based on Kenneth Cook’s 1961 novel of the same name, the film follows John Grant (Gary Bond), a disgruntled intellectual from the big city who is unhappy with his teaching job in a Podunk town. On his way back to Sydney during a school-year break, Grant becomes stuck in an Outback community, Bundanyabba (known as “The Yabba”). The men of The Yabba are a hedonistic lot, who like drinking, wrestling, gambling, and shooting kangaroos. Despite the condescension with which Grant views these men, he finds himself pulled further and further into the Yabba way of life.

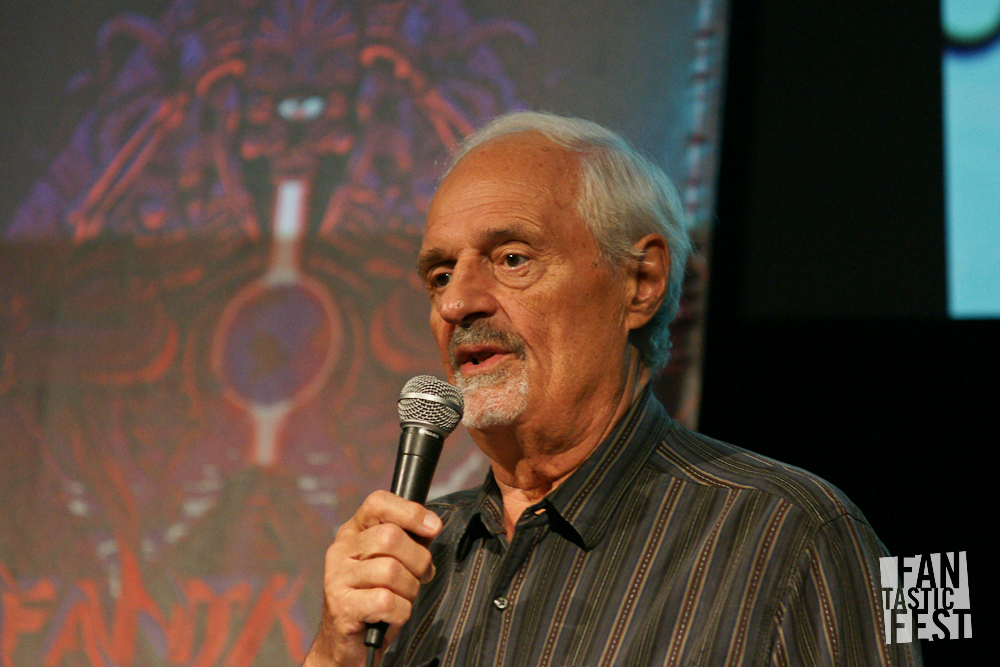

Originally released in 1971, Wake in Fright made a splash at the Cannes Film Festival and eventually became a national treasure in Australia. Yet it never made it to VHS. Or DVD. Or even television. No prints of the film could be found, and the film’s negative was completely lost. I sat down with director Ted Kotcheff in Austin to talk about the amazing story of Wake in Fright‘s rebirth.

Josh Miller: What initially drew you to the project? Were you already familiar with Kenneth Cook’s book?

Ted Kotcheff: No. I had worked on a film in 1967 called Two Gentlemen Sharing, about the racial situation in London. I was living in London. And the guy who wrote the script, Evan Jones, we became very good friends. And one day he said to me, “You know, Ted, I’ve been hired to do an adaptation of this Australian book called Wake in Fright, by Kenneth Cook. It’s right up your alley. I know you. You’ll love it.” So I read it and I did love it. He knew me so well. I really responded to the atmosphere of the book, the Outback, the central character, and the incredible tension.

One of the things I’ve realized about myself in retrospect, is that I’m always attracted to people, to central characters, who don’t know themselves. And they don’t know what they’re capable of, they don’t know what is driving them. And in this case with [John Grant] he REALLY did not know himself or what he was capable of under extreme circumstances and experiences. And I think that is true of all of us sometimes. You put yourself into situations where you can encounter yourself. At least I have. I want to know what’s the dark shadow side of one’s character. You’ll notice in the film, continually, there are lights flashed on [John Grant’s] face.

Josh: Like in the scene where he’s woken up, hung-over, by the light shining in through the hole in the roof?

Kotcheff: Right. Because it is as if the shadow side of him is being illuminated.

Josh: Why do you think you’re drawn to such characters? You seem like a very fun-loving guy. And you locked into your dream career at a fairly young age, [Kotcheff got his first major directing position at the age of twenty-four] so you certainly weren’t as adrift in life as John Grant.

Kotcheff: No, it’s true. That wasn’t me. But I think there is a shadow side to everybody. Where you wonder, if under certain circumstances, you might do things you’d be ashamed of.

Josh: I’m not familiar with Kenneth Cook’s book. How similar is the film?

Kotcheff: The film is very loyal to the book. The guy who wrote it, he had been in that same town, Broken Hill [which stood in for The Yabba]. He had a job working on the local paper or something. And he went through this horrible experience.

Josh: And he was a big city guy?

Kotcheff: Yes. He was from Sydney. And then he was out in this small town in the Outback. So it was a very autobiographical record of his experiences. So we were pretty loyal to the atmosphere of the book. And its story.

Josh: So jumping forward a bit. I’m personally very fascinated by lost films that are rediscovered decades later. There is just something special and even inspiring in a way by stories like this. And Wake in Fright has been missing since the 1970s. It has been gone for a lifetime — my entire lifetime, at least — kept alive solely by the impact it had on those who saw it back in 1971. I can only assume the situation is a hundred times more fascinating and emotional for you.

Kotcheff: I tell you, Joshua, it was miraculous. The craziest thing is I did not know it was lost. They didn’t tell me. And I’m glad they didn’t tell me until they found it again. Otherwise the little hair that I have left, I would have lost totally. You just take these things for granted. You make a film; it never occurs to you it might be completely lost. It’s not unusual, I have discovered, for the negative of even newer films to be lost. Especially for a film like this. It was an artistic success; got great reviews — at Cannes, in New York, Pauline Kael. But it did no business. Nobody came to see it. So [the studio and the distributor didn’t] really cared about it.

Josh: How was it received in Australia?

Kotcheff: Well, the critics loved it. But the popular reaction was very lukewarm because they didn’t like the way the Aussie male had been depicted. It was pretty harsh. Although I felt for them, I don’t go around condemning [people in my work]. I’m not judging my characters. I’m their witness.

At any rate, it was only twenty years later, that one of the producers was looking for it, thinking, “Hey, this is a seminal Australian film. Where is it?!” And there were no prints. Anywhere in the world. They found one print in Dublin, but it was in tatters. They searched for ten years. Finally, it was the editor, Anthony Buckley, who loved the film, and who with his own money found the film. He went London, to Dublin, New York, Canada, all over the place. Finally he tracked it down to a warehouse in Pittsburgh. And it was in two big boxes the said FOR DESTRUCTION on it!

Josh: Was the warehouse cleaning everything out or something?

Kotcheff: They were going to burn it! If he had come just one week later, it would have been incinerated. With no trace of it left!

Josh: That sounds like a movie itself!

Kotcheff: I know!

Josh: If the film played at Cannes I have to assume it got an international release, at least some places in Europe. Was there anywhere the film found some traction? Or did the general public just dismiss it everywhere?

Kotcheff: The French loved it. Especially the French critics. There was one guy who was besotted with the film. And he was on television. Very big television critic. And everyone listened to what he had to say. And he went crazy over the film. He had me on TV three times over the film.

Josh: All during its initial release?

Kotcheff: Yes, all in 1971! All during the Cannes festival. I was there for two weeks. He had me there three times. And he kept calling me “The Master.” He loved the film. As a result it did great in France. Otherwise, nothing. It did nothing elsewhere. In New York, despite being well-received by critics – Rex Reed called it one of the best films of 1971, Pauline Kael loved it – despite all that, United Artists said no one would come see it. They changed the title. They thought Wake in Fright sounded too much like a Hitchcock film. And I said, “That’s bad?” So they called it Outback. And I said that now it sounded like a National Geographic documentary. Please don’t call it that! But with distributors there are two areas where you don’t win, and that’s with titles and endings.

They opened it New York, on one screen, in a small movie house, on a Sunday. During a heavy blizzard!

Josh: That was the only place it opened in the entire country?

Kotcheff: Yes! And no one came. Then they said, “See, Ted, we told you no one would come.”

Josh: Speaking of the title. Wake in Fright is much more intriguing than Outback. Though it does make the film seem like more of a thriller than it is. I am curious what the title means.

Kotcheff: It comes from an Australian folk-saying. “May you dream of the devil and wake in fright.” And it means that there is a dark side in all of us, as I was saying before. The idea is that it is frighting to wake up to the reality of who you are and what you’re capable of.

Josh: Correct me if I’m wrong, but now that the restored version of the film has played Cannes again, Wake in Fright is only the second movie to ever play twice at the festival. [The other is Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura.]

Kotcheff: Yes and it is all thanks to Martin Scorcese, all because he remembered it from Cannes back in 1971. And when he heard that the film had been digital restored, he asked to see it again. And screened it again [in 2009] as part of the Cannes Classics. I have eternal gratitude to him.

Josh: Did you talk with him at Cannes in 1971? He hadn’t made many movies by then.

Kotcheff: He was a twenty-five-year-old kid! Boy, have I got a story. So I was sitting in the balcony at the screening [of Wake in Fright at Cannes]. And they put the director in the front row of the balcony. And the film starts. Then there is this voice behind me going, “Wow. Wow, what a scene. Boy. I didn’t expect that. This is great.” Of course, comments of approbation are music to a director’s ears. But it was unusual that he was American. It was Cannes. And I knew he was a filmmaker because only directors, producers, and writers are allowed to sit in that area, in the first balcony. And this guy just keeps going on and on. So you’ve seen the film. There’s the homosexual rape scene. Which may be nothing now, but in 1971 it was out-there. And the scene comes on and this guy behind me says, “This director. He’s going to go all the way. He’s going to go all the way. He’s going all the way! Oh my god he went all the way!”

So afterwords, the movie ends, the lights come up and I turn around to look at him. He’s this young America, with spectacles. I go outside. And the film’s PR guy comes up and asked how it was going. I said, “Good. But there was this guy sitting behind me. This American. And he kept talking; really liked the film.” At that moment the guy came out of the theater and I pointed at him. “Oh, yeah, he’s a young America filmmaker. Only made one film and it flopped.” So I asked if he knew the guy’s name. “You don’t need to know him.” I didn’t give a crap, I wanted to know his name. So he asks another person standing nearby if they knew the kid, and this guy says, “Yeah. His name is Martin Scorsese.” And I said, “You’re right. I’ve never heard of him.”

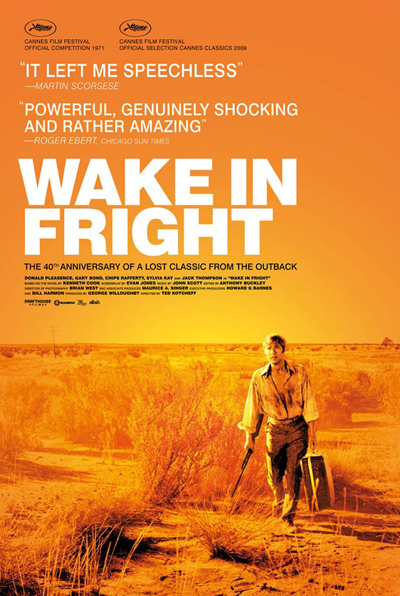

And after it was restored, when it was declared a Cannes Classic. You know who declared it a Cannes Classic, who was heard of the Cannes Classic department? Martin Scorsese. He remembered the film after all those years. 38 years. I found that one of the most moving things of my creative life. And his generosity has not stopped. There’s a line on the new poster that says, “It left me speechless.” He gave it to us last week to put on the poster.

And I only met him once. At an Oscar party. I saw him with DeNiro. So I went over to him, and Scorsese got all excited and started telling DeNiro who I was and how much he liked my film. And then later I told DeNiro the story about Cannes that I just told you, and he said, “Ted, he talks through everybody’s films! And not always complimentary either.”

Josh: Oh man. That’s a story right there.

Kotcheff: It is just so nice that people really respond to the film.

Josh: What do you think it is about the film that has created these strong reactions? That had people scouring the globe looking for it?

Kotcheff: That’s a very good question. And I’ve pondered it long and hard. And I don’t think I’ve ever had a definitive answer. I think everybody has a desire for self-knowledge. And this already sounds a bit too philosophical. But everybody has desire for this knowledge. We go into situations where we confront ourselves. And I think the film epitomizes that. Plus the setting is exotic. Incredible atmosphere — the heat and the dust and the kangaroo hunting and the drinking, it becomes a feverish nightmare. There’s something about it that captures people’s imagination, I guess.

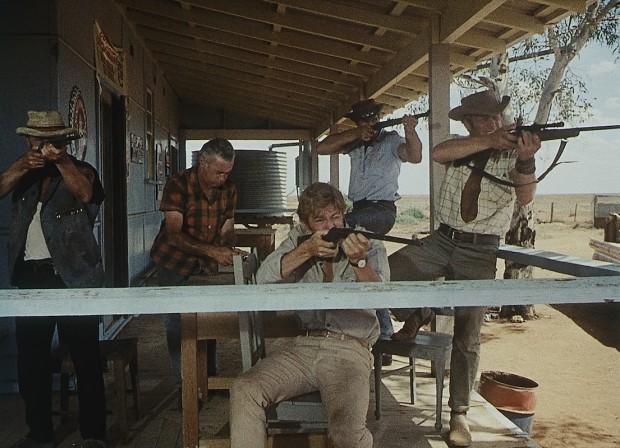

Josh: One last quick question before I set you free. The kangaroo hunting sequence you just referenced is extremely disturbing and has no doubt caused some controversy because it shows real kangaroos being killed. And it isn’t stock footage. Yet you didn’t actually kill them for the film. Our PETA-friendly readers would probably like to know how you came about the footage.

Kotcheff: It was a professional kangaroo hunt that we piggybacked along with. I was in the back of the truck. And it had the exact same set-up as in the movie, with a light that they’d use to hypnotize the karangoos with. And I just stood in the back of the truck and it was like I was making a documentary film. I hate to say it, but using the footage gave us tremendous reality. And I was encouraged in all this by the Australian Prevention for the Cruelty of Animals. Because nobody knew they were killing hundreds of kangaroos back then to be sold to America as pet food.

Josh: What?

Kotcheff: Yup. They’d kill ’em, then skin ’em. The skins were used to make those cuddly little koala bears tourists would buy. And then the carcasses where shipped to America to be sold to the pet food industry. Your dogs and cats were eating kangaroo meat! That was the real scandal of it all. One thing I am proud of — some of the footage, some of the footage that was too horrendous to be used in the film — the Australian environmental people used it. And they finally outlawed killing kangaroos to be shipped to America as pet food. They’d killed hundreds every night! It’s incredible.

_____________________________________________

The restored Wake in Fright will open theatrically this month in select markets. Do yourself and cinema a favor and go see it. Even if there is a blizzard.

10/12-Boston, Austin

10/17-Washington

10/19- Los Angeles, Portland

10/26- San Francisco, Phoenix, Berkeley, Seattle, Santa Fe, New Orleans

11/2- Hartford, Chicago, Detroit, Grand Rapids

11/8- Boulder

11/9- Nashville

11/16-Philadelphia, Columbus, Denver

12/1- Baltimore

12/7- Atlanta

12/14- Minneapolis