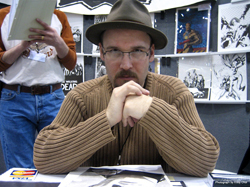

It was two in the afternoon and Ed Brubaker was on the phone with me slurring his words. It’s easy to imagine Brubaker, the guy who killed Captain America and who has written hard-bitten crime comics like Lowlife, Sleeper and now Criminal, as sitting at his computer with an open bottle of bourbon and a rumpled shirt with a tie open at his neck, cigarette smoke spiralling up into a lazily spinning ceiling fan… but in reality the guy just came from the dentist.

It was two in the afternoon and Ed Brubaker was on the phone with me slurring his words. It’s easy to imagine Brubaker, the guy who killed Captain America and who has written hard-bitten crime comics like Lowlife, Sleeper and now Criminal, as sitting at his computer with an open bottle of bourbon and a rumpled shirt with a tie open at his neck, cigarette smoke spiralling up into a lazily spinning ceiling fan… but in reality the guy just came from the dentist.

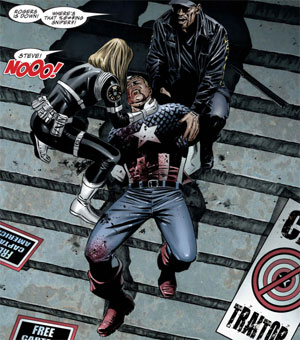

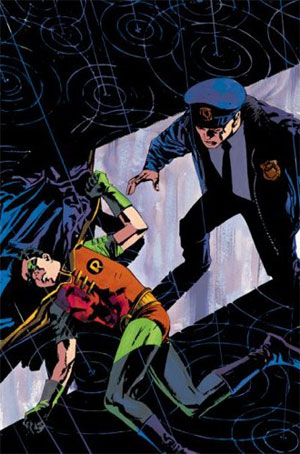

As you’ll read in the interview, Ed’s hardest-edged days are probably behind him, but his best writing days are happening now. Ever since moving from the DC Universe, where he wrote the truly incredible series Sleeper and co-wrote one of my all-time favorite comics, Gotham Central (imagine Homicide: Life on the Street set in Gotham City), Ed’s been tearing shit up at Marvel. Aside from a stellar run on Captain America that recently brought the American icon down by assassination, Brubaker has been continuing a streak of great Daredevil stories (that character’s at his best since the days of Frank Miller), getting all mutanted up with X-Men and now has his own creator-owned crime comic, Criminal, from Marvel’s Icon imprint.

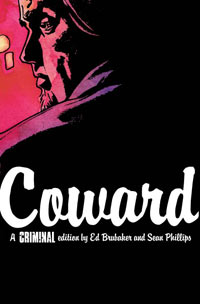

The first volume of Criminal, featuring art by the always impressive Sean Philips and called Coward, is out in trade paperback right now (buy it by clicking here), and it’s a major reminder that the medium of comics can be used to much better effect than just having guys in spandex punch each other. The first volume collects issues one through five; issue six, starting a new arc called Lawless, is on stands now. The final trade paperback collection of Gotham Central also hit stores last week (buy that here), and while I hate what the DC editorial dopes have done with two major characters from that series, the book went out as strong as it came in.

Special thanks has to go to my late friend Dan Epstein, who put Ed Brubaker in touch with me. Dan knew I wanted to do more comic creator interviews but never had the get and up and go that he did to hunt them down. This interview wouldn’t exist without Dan Epstein.

What is it that attracts you to crime stories?

I kind of always attracted to them growing up, I think. My uncle was a noir screenwriter in the 40s and 50s, so I grew up with those movies around a lot. But growing up reading superhero comics and watching cartoons, even Bullwinkle and Rocky is about crime – they’re always trying to stop Boris Badenov from doing something. It seems like there’s some kind of crime or mystery in every story, even fiction aimed at kids. The other part of it is that I was an alternative cartoonist from when I was 18 until I was in my late 20s; I used to write and draw comics, and a lot of what I wrote about was semi-autobiographical. When I got out of wanting to write about myself I noticed, reading a lot of private eye novels, the same kind of narrative voice came across. It was a first person narrator talking about the world and they way they viewed it, but it has so much more of a plot involved. I think that was one of the things that made me think maybe I could write a mystery, and once I started writing mysteries I started seeing mysteries everywhere – almost anything that happens I say, ‘That’s a great premise to start a mystery from.’

That’s part of it, but they say write from experience, and I’ve had various different periods of my life when I was living on a more shady side of the law. When I was in high school my friends and I were into drugs and were pretty belligerent, punk rock assholes into vandalism. We were the guys who, if you had a party when your parents were out of town, would raid your medicine cabinet. As I got a little bit older, after high school, I sort of lived among that life for a few years, where you don’t sleep a lot and you stay up three or four nights in a row and you get paranoid and you get into fights with people. You sit in drug dealers’ houses and watch people you don’t know walk around with guns and all sorts of craziness happening. After a few years of living that life I really wanted to get away from it. I did some things I’m not proud of at all – twentysomething years later it’s good fodder for stories, but for a while I was ashamed of what I did and what I’d been through. A lot of it is I can see that world still; I can see a world where the idea of ‘This is against the law’ is true in theory, if you don’t get caught.

With Criminal you’re looking at the crime story from the criminal point of view. Does there always have to be a kind of morality to the character you’re writing about, or could you write a story about a truly evil person?

With Criminal you’re looking at the crime story from the criminal point of view. Does there always have to be a kind of morality to the character you’re writing about, or could you write a story about a truly evil person?

You probably could. I certainly would love to, but I think to get reader empathy, even if you had a completely amoral or evil person, the reader’s need to get a sense of some way to identify with that character and to agree that there’s something done to the person that made them like that. Look at the Ripley series that Patricia Highsmith did; I’ve had friends tell me they get halfway through the second or third book in that series and they can’t read it anymore because Ripley is just a survivor and he’ll do anything to anybody so he doesn’t have his picture of what his life is going to be damaged at all. So there you go, a completely amoral, mostly evil person, and he’s the star of five books that were all bestsellers in their day, and a couple of them adapted into really good movies.

I choose to tackle the characters that are a little bit more, ‘I’m a criminal but I’m not an evil person, this is the just the world I live in.’ You look at the Parker novels by Richard Stark, and Parker clearly does not care about anybody but himself – but at the same time the reason why he doesn’t kill innocent bystanders isn’t because ‘Boo hoo, I killed an innocent person,’ it’s because if you kill an innocent bystander it’s a whole of a hell lot harder to get out of town. It’s all about survival and being smart. I think that, just like anywhere else in the world, there are as many evil people or asshole people living on either side of the law. I’ve met plenty of police officers in my day who I would consider evil – I had a guy who confiscated my scooter, and he told me he confiscated my scooter because his wife hadn’t fucked him that morning. If that isn’t evil, I don’t know what is. He made me walk home in pouring rain for four hours!

I think when you write from the point of view of the criminal, you try to find your own way in. You’re always writing about yourself to a degree, and like with Coward I was really writing about the frustration I have about rage inside myself at the world. The storyline I’m writing now for Criminal, Lawless, is really about family history and relationships I have with brothers; the strange relationship brothers have where even if you don’t like each other you have a kinship and can feel guilt and responsible all the time for your family. That, more than anything, is what it’s really about… but it’s also about a bunch of guys killing people and doing a heist.

I try to remind myself more and more that the people who are actually professional criminals in real life, while they may be smart and clever, there are plenty of people who live in that world who are complete fucking pricks and complete assholes. A lot of them are on a lot of drugs and are drunks; their concept of the world is completely different. I prefer the noir version of that as opposed to the real version, where there’s a romanticism to them not being a part of the world, where they view people like us who pay taxes and vote with utter contempt because we bought the illusion.

Coward is self-contained in that it has a full story, and then Lawless is going to be self-contained as well… but they have a small connection, right?

Yeah. They exist in the same world in the way Elmore Leonard’s characters all exist in the same world and a lot of them know each other. One of them may take center stage and then fade into the background for the next story.

And that’s the general plan for Criminal – these stand-alone but interwoven arcs?

That’s the plan. I’m bouncing around a bunch of ideas for what to do after Lawless. There are so many stories I want to tell. I’m thinking of doing three standalone stories that are a little longer, thirty or thirty-two page issues, and then have those be standalone stories that actually link together to tell a crime story from three different perspectives. To use the crime at the center as pivot to tell the stories about the characters. That’s because I like people to be able to buy a single issue; I’d love to be able to give someone an issue of Criminal that’s a self-contained story, and then the next issue is also a self-contained story, but if you read them both you see the links between them.

With the main story that I’m serializing I wanted it to be that you could give any trade paperback to anybody. If it’s volume three or volume four they don’t have to have read volumes one through three to get it. As much as I love Y: The Last Man or Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing or Sandman or Fables or 100 Bullets, I’m never going to be able to give anyone 100 Bullets Volume 8 and say, ‘Read this one, it’s the best one’ – they have to read volumes one through seven first. With Criminal I wanted it to be much more like you can read Rum Punch before you read the book that the characters were in before that. With the Parker novels they’re in a sequence, but if you feel like it you could pick any one up and read the book.

With this book, which is creator owned, you can have a beginning, middle and end to the stories you’re telling. That’s so different from the serialized mainstream books, which were going long before you got there and will go on long after you leave. How do you approach those different kinds of storytelling?

It’s a different mindframe, in a way, but as a writer you’re always thinking in terms of where the characters will go after the story… unless they’re all dead, so in noir you do it less. Dickens did it in his book, ending with a chapter that said what happened to the characters up until they died. With the superhero stuff I think the reason some of my friends who got in the 90s and didn’t last doing the mainstream superhero writing is that they didn’t feel like it was their real work. They didn’t make the characters their own enough, and I think with Daredevil, with Captain America, with X-Men and Iron Fist, we take those characters and make them our own, and we’re willing to break them. We’re willing to push them into places where, if you were being too precious or worrying about the fact that you don’t own this character, you wouldn’t do it. But you have to make a mental switch in your head where you go, ‘OK, I don’t own Daredevil, but if I was reading Daredevil, what would I think was kick-ass? What would shock me? What would make me keep coming back every month?’

I always liken it to the pulps, really. Like if you were writing The Shadow or Doc Savage you have to know that someone will come along the minute you’re done writing it, but you can’t think about it like that. You can only think about it as, ‘What’s my story and what’s my character’s arc, and where does he go from there?’ It’s really the same for me – I don’t make a differentiation in my head when writing Criminal versus writing Daredevil or Cap. I think about all the things I know about the characters; with Criminal I just know it in a different way than I know Daredevil or Cap. With Daredevil or Cap I know it because I read all the back issues, so I know how they would react or I’d look at the back issues and say, ‘This guy got it wrong, that’s not how Daredevil would have reacted.’ But you’re always doing your version of it, and if you’re doing it right, you’re doing it without fear. Like Daredevil.

have to know that someone will come along the minute you’re done writing it, but you can’t think about it like that. You can only think about it as, ‘What’s my story and what’s my character’s arc, and where does he go from there?’ It’s really the same for me – I don’t make a differentiation in my head when writing Criminal versus writing Daredevil or Cap. I think about all the things I know about the characters; with Criminal I just know it in a different way than I know Daredevil or Cap. With Daredevil or Cap I know it because I read all the back issues, so I know how they would react or I’d look at the back issues and say, ‘This guy got it wrong, that’s not how Daredevil would have reacted.’ But you’re always doing your version of it, and if you’re doing it right, you’re doing it without fear. Like Daredevil.

Isn’t there a point where it become impossible to shock the mainstream audience? I don’t know what your long term plans are for Captain America, but you and I both know that some day it will again be Steve Rogers in that suit. Does it become pointless to continue on with these serialized characters, since the readers know they’ll end up back at the status quo? Is there a way to keep it fresh?

It’s not so much about the shock – sure, when you kill a character there’s always a shock value to it – but there has to be a reason. For me, killing Captain America means I finally get to explore what Captain America and what Steve Rogers actually mean. When he’s running around in the book he takes up so much attention you can’t stop and go, ‘What does he stand for?’ Plus, I hate when he stops and gives a big speech, because he’s a superhero so it just seems… I don’t know, it’s a comic book – there are enough people standing around talking to move the plot forward; Captain America standing around talking about what he means or what America means, even as a kid that bored me to tears. You can’t really say anything controversial anyway, because it’s a comic book. That aspect never appealed to me, so taking him out of the book and exploring the vacuum is interesting and is something I don’t think has been done in the way I’m doing it.

If you look at it as, ‘Is there really a point in continuing any of these characters,’ it’s a double edged sword. If you continue these characters you’re continuing the way American comics work, where the publishers own all these characters. Someone was pointing out that the difference between the American industry and the Japanese industry is that the reason why American comics do so many superheroes is because the companies own those characters, so it behooves them to keep them going. Whereas when people bring in new concepts we generally don’t bring in new superhero concepts, because there are already 500 superhero comics coming out a month – what’s the point of being the tiniest fish in a giant pond?

So yeah, I’m conflicted about it. I make a good living writing superhero comics, and I read some written by my friends that I like, but I don’t see it as the be-all, end-all of comics either. But I also love serialized fiction, and within serialized fiction you have a grand tradition of shocking things happening to the characters. People were up in arms when Conan Doyle killed Sherlock Holmes.

Oh yeah. That’s why they brought him back.

Exactly. That’s the first time outside the Bible that they did something like that with a character!

With this Captain America story, for example, where you want to explore certain themes and concepts, how much leeway do you have to do that in today’s publishing environment? You’re exploring a world without a Cap but then there’s World War Hulk and then there’s whatever comes after that, and you have to have your tie-in issue.

I don’t have any of that stuff coming up, thankfully. I’m fortunate that I’m not some guy fresh off the boat; I was hired by Marvel because they knew what I had done before and I had a pretty good reputation coming in and they saw they could put me on bigger books and make a bigger name for me. They succeeded at that, and the reason they succeeded is that I’ve been doing this a while and know what to do. I talked to my editors a lot about what I’m going to do, but they don’t force me – and I don’t think they force a lot of people – to be a part of those crossovers if I don’t want to be. With Civil War there was no way around having a couple of issues of Cap take place during Civil War, but for the first four months of Civil War – or what was supposed to be the first four months of Civil War! – I had a story where Cap was in London. They don’t force as much on me, but I think part of that is because I expressed early on that I wasn’t interested in doing that and breaking up the stories I was telling with my books. I have a pretty good map of where I’m heading with all my books, and it makes no sense to suddenly have an issue of Daredevil all about Civil War when I have Daredevil running around Europe.

I’ve been through that storm at DC, working in the Bat office where every three months you’re asked to tie into something or the minute you finish some storyline you’re starting a yearlong event where you’re chapter four. I’ve been through that enough to know that, for me at least, that’s not the way I like to create. It’s fun once in a while, like for instance in X-Men we’re doing a thing where for three months we’ll all tell one long story. I got to do the first two chapters, and that seems to be the best way to go – write the first two and you can really help set the tone for it. Now I have to write two more chapters for the whole thing and I’m really looking forward to that, because I haven’t done something like that for three or four years now. It’s kind of fun, but those things can be nightmares of logistics. I’ve seen the drafts of Civil War, and I think there were six or seven drafts of every issue because the scripts would come in and every person who had a character in it would have a note about something or other. I was just like baffled by some of the changes – it would a line edit, but every page had 80 line edits. Everybody had input because you’re using every character and every character is important for various people’s books.

Gotham Central was, I think, one of the best books on the market when it was being published, but it had a hard time finding an audience. Do you think that we’re going to be able to break out of the superhero thing and reach larger audiences with books that aren’t featuring guys in spandex?

Gotham Central was, I think, one of the best books on the market when it was being published, but it had a hard time finding an audience. Do you think that we’re going to be able to break out of the superhero thing and reach larger audiences with books that aren’t featuring guys in spandex?

I hope so. The best selling books you’ve had in bookstores over the last few years are things like Naruto, V For Vendetta or 300 or Sin City. If you notice the best of the comic book movies that seem to spark sales of the product are the ones where it’s a single book. Road to Perdition sold a couple hundred thousand copies after the movie came out; a lot of people didn’t know it was a graphic novel to begin with. History of Violence, which I think has been my favorite adaptation of a book, sold plenty of copies of the trade paperback. I think that’s part of how we break out of that cycle.

But I think the Marvel and DC superhero empires are, for better or worse – and right now, I’m really enjoying Marvel and what Marvel is doing and I’m enjoying being there – not going to change. They know what they’re doing and they’re good at making money doing it. They would have to start losing money so badly like comic publishers did in the early 50s to try to find the next thing to hit it big. Even manga – you hear various numbers of how much the manga books sell in bookstores, but they point out the five or six things that sell amazingly well, but they don’t point out the 700 manga things sitting on the shelf at Barnes & Noble that you never heard of. All of that stuff, they didn’t have to pay anyone to produce it – it’s all pre-produced and they just paid someone to translate it into English; they don’t even flip the art anymore. They probably paid translators a bit of money and production a bit of money, but it’s nowhere near the cost of generating a 300 page graphic novel.

I think for better or worse we’re a little bit stuck with the system that we have at least through Marvel at DC. But DC has Wildstorm and Vertigo, and Marvel is starting to do other stuff. Marvel had huge success with the Stephen King adaptation, and they’re probably talking to more people about stuff like that. It’ll be slow because the superhero has such a firm grip on the direct market. You almost want to call it a death grip. But at the same time, Criminal is probably selling better than most crime novels by somebody nobody ever heard of. We’ve sold a lot of the trade paperback already, and we’re moving like 20,000 copies of every issue so far.

It’s a tough market, but it is what it is. I used to feel that I wanted DC and Marvel to go away and have this market that would be different than that, somehow, but there isn’t enough material outside of Marvel and DC to maintain the direct market. Everything beyond the exclusive publishers in the Previews catalog are so badly ordered by most of the stores that there’s no way they could maintain it. You always need popular material to maintain a system. Even in the European comics market, where you hear how wonderful it is, if you talk to people who work in the European comics market, it’s just like here: there are some things that really, really well, but the things that sell best are always some kind of adventure or scifi or something. They’re not Blankets or something. Look at XIII, which is basically like The Bourne Identity – that’s the biggest comic in Europe right now, and they sell three million copies every time they put out a book of it. The books are only 48 pages long, though, and if it were me I’d be putting one out every two months, based on the three million sales number!

We’re reaching a lot more people on Criminal than we were on Sleeper already by virtue of being in the Marvel catalog. There are a lot of stores that won’t order outside of the Marvel catalog, or the top twenty DC books.

The Criminal single issues had these text pieces by guest writers– are you punishing me for waiting for the trade by not reprinting them?

No, I’m not punishing you… I’m rewarding people who bought the single issues! The text pieces don’t have anything to do with the story. It’s like if you bought a novel by James M Cain and in the back of it it had eight movie reviews by pals of James M Cain, you’d be like, ‘What the hell is this?’

The way I perceive Criminal is that Criminal is a magazine. We serialize our comic story in it, and we have letters pages, I have little rambling text pieces and every month we have some form of article or short story or something in the back that is something you can only get in that magazine. It’s a comics magazine for people who like noir and crime stuff. These are fun things we use to fill the back pages. It rewards the people who make it happen; like a lot of creator owned books, we own everything but we don’t get page rates for producing it. I don’t get paid to write Criminal. I write the book and send it to Sean and all the money the book makes goes to paying us to produce it. I need to make sure the book sells enough each month to pay my artist before I think of taking anything. The people who buy that book every month on the stands are the people who are making us be able to have those trade paperbacks. But also we didn’t have any room in the trades if we wanted it to be there.

I want every book to be a stand on its own crime graphic novel, and yeah if you read them in order there are Easter eggs. If you read issue 6 there’s a character from issue 5 who people are asking, ‘What happened to her?’ We don’t draw attention to her but there she is, and it seems like another detail in the story.  I said from day one that the extra stuff wouldn’t be in the trade paperbacks. And we work our asses off to get that stuff in there, believe me! I’m waiting for two different articles for the next couple of issues; I don’t pay these guys to do it so I can’t hassle them too badly. But when Josh Olsen offers to write a thing for The Silent Partner, I’m over the moon!

I said from day one that the extra stuff wouldn’t be in the trade paperbacks. And we work our asses off to get that stuff in there, believe me! I’m waiting for two different articles for the next couple of issues; I don’t pay these guys to do it so I can’t hassle them too badly. But when Josh Olsen offers to write a thing for The Silent Partner, I’m over the moon!

Well, you’ve convinced me to buy the individual issues now.

We’re doing well. We’re not in any danger at this point, and I don’t think we’re going to be. We’ve got pretty good European sales and between the money we make over here and the European sales, I’ve made enough to pay my guys.

Has Hollywood come calling about Criminal?

They’ve come calling a lot but I haven’t made any deals with anybody yet. I’ve been on the phone with people, nothing I can talk about too much. There have been a couple of actors who’ve really wanted to get Coward as a starring vehicle for them. It’s been kind of crazy, actually – I spent four hours on the phone last with a hot young director (well he’s not that young, he’s a couple of years younger than me), a guy who has a lot of heat right now, and he really wants to make it. Later this week I’m having a conference call with my manager and a producer and director who want to make it. It seems like not a week goes by where I don’t have somebody inquiring with my manager.

Would you want to write the script, or would you let someone else do that?

I’m attached to write anything that happens with Criminal – unless they’re willing to pay enough for the privilege of me not writing. And I know the whole story. The director that I talked to the other day, I really hit it off with this guy, and he was saying he would actually give the graphic novel to producers who want to make the movie and he would say, ‘Read this. Consider this the first draft. This is basically the movie.’ I liked hearing that a lot. But yeah, I’ve written a couple of screenplays, one that I’m proud of, and one I would never show anybody. I have one that’s on the verge of being made with David Goyer, so we’re just waiting to get all the financing and casting in place. It seemed like it never was going to happen and then a few months ago a bunch of financiers read the script and came forward and said, ‘We’ll give you money, just get a cast locked up.’

My gut feeling is that I see a lot of movies, I’ve read a lot of scripts and I write for a living – what’s the worst that I could do? I see a lot of movies, and most of them suck. How bad could I do? I’ve already written the story! I don’t hope my first draft of anything would be as good as Kiss Kiss Bang Bang or The Lookout, but I can aim at that. And I’m good at dialogue, and the hardest part of a screenplay is the structure and the dialogue. I’ve been doing this for a decade and the technical details of writing a script are taken care of by a program at this point.

Which script is that?

It’s called The Fall. It’s adapted a short comic I did in the late 90s with Jason Lutes. It’s a slacker noir. It’s pretty strange to be in this place where people are reading the script. Even that seems odd to me. But I’ve told [my management] that I don’t want to go down to LA every week for some bullshit meeting with somebody who wants to meet me just because they heard I killed Captain America!