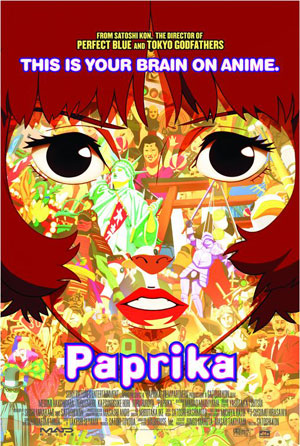

Satoshi Kon is considered one of the giants of anime. His previous films, like Perfect Blue, Millenium Actress and Tokyo Godfathers, have made big splashes not just among the otaku of America but also the critical community. His latest, Paprika, played the New York Film Festival last year and has now been given a stateside release. A psychedelic (and baffling) trip through the dream world, Paprika has been mostly met with positive reviews (read my take on the film here).

Satoshi Kon is considered one of the giants of anime. His previous films, like Perfect Blue, Millenium Actress and Tokyo Godfathers, have made big splashes not just among the otaku of America but also the critical community. His latest, Paprika, played the New York Film Festival last year and has now been given a stateside release. A psychedelic (and baffling) trip through the dream world, Paprika has been mostly met with positive reviews (read my take on the film here).

I interviewed Kon at a Park Avenue hotel where a translator helped bridge the language gap. I never know what the proper etiquette is when meeting a Japanese person – do I bow, do we shake hands, what? I did both here, but I always feel like something out of Shogun when first meeting someone from Japan, like a smelly, hairy barbarian. Kon was the picture of precise and neat bohemia, with a goatee and long ponytail. He was an engaging interview, and sadly our thirty minutes was up pretty fast because of the back and forth with the translator.

How does the development of something like Paprika, which is based on a novel, differ from the development of an original concept?

I don’t distinguish in terms of process between something that is an original work and something that is based on a novel. It’s more about what is interesting, what is wonderful about the ideas I’m working with. The main difference is that there’s an original novel that this was based on, and what was important, what was a priority, was protecting what we felt was wonderful and interesting about the original work.

I haven’t read the original novel, so with this is it that you want to protect the spirit of the book, or is it that you want to protect specific relationships or characters?

The original novel it’s based on is a work of great volume that couldn’t be made into a 90 minute feature film if it was faithfully adapted bit by bit. I was a huge fan of the work from the time it first came out. I was also a great admirer of the writer, Tsutsui Yasutaka. What I was most drawn to about the novel, initially, is the idea of being able to go into another person’s dream. I thought there is a mystery to the imagery that are within dreams. Also the idea of the invention being used by evil forces, for evil purposes instead of dreams.

Did you use your own dreams as the template for some of the dreams in Paprika?

I did of course reference some of my own dreams; on a day to day basis I would take notes on my own dreams and try to think of what influenced them. I also read into psychologist’s writings on dreams and more academic textbooks on dreams. Out of that, there was one particular book that asserted in the world of dreams and dream logic it’s less about the relationship of ‘I do this to you’ and cause and effect but it’s about association through imagery. That’s the big difference between the real world and the dream world, and it’s less about whom does what to whom since the objects of that action in a dream may change quickly, and it’s more about the association moving from images to images. That thinking greatly influenced the way we approached the dream world in this film.

You said that the book was so big that it could never be made into a faithfully adapted 90 minute movie. You’ve worked in television as well – do you find that working in TV is more freeing, creatively, or do you like having the structure of the 90 minute movie?

Depending on what the idea of the project is, some mediums are more suited for a particular idea. As far as TV series goes, the schedule is generally much tighter, and the budgets are much smaller as well. You have to choose which part you want to emphasize – if it’s an interesting story you have to tell the story right, so it’s a little bit of a challenge. As far as a feature film goes, the final length may only be 90 minutes or two hours, but you do have a much bigger budget to work with and much more time on the schedule so you’re able to produce something that is higher quality. While there may be fewer minutes to work with than a TV series, it’s more packed full of quality per minute than a TV series is. I prefer film.

In America 2D hand-drawn animation seems to be on its way out, while it’s still going strong in Japan. Do you think that Japan will continue producing 2D hand drawn animation, or will you eventually turn to the 3D computer animation that’s so popular in America?

3D animation is growing in Japan, and I think it will continue to grow and there is a movement to develop it further. But I don’t think it will ever be like it is in America; for one thing there is a culture of manga, where people of all ages and backgrounds enjoy reading comics. To take the comics that are drawn by hand two dimensionally, the attractive part about the characters, physically and their expressions, don’t work out well in 3D. With anime films there often are original scripts developed just for the film, but often they are adapted from comic books. Stories and characters are taken from manga. For that reason I don’t think 3D animation will be as big in Japan as it is in America.

Obviously in 2D animation, even hand drawn animation, uses computers to some extent to supplement. How does Madhouse use computers in the animation process?

Most of the film is drawn by hand, but the composites are done in the computer. In Paprika there are moments that are a combination of hand drawn and computer elements. For instance there’s a scene where the hallways start to wobble and distort, or another scene where a room is drawn into a hole – that’s a hybrid of hand drawn animation and computer effects. So that’s how I personally prefer it, where the foundation is hand drawn and the computer effects are hybridized into it. That’s the direction most Japanese animation is moving in.

When I was growing up, Japanese animation was a fringe thing in America. Some people knew about it, and there was some anime that ran on TV, but now it’s becoming more and more of a mainstream part of the American culture. Where do you see the integration of anime and American culture going in the 21st century?

Even in Japan we do hear that anime is becoming very popular in America, and it might make some people think that if Japanese anime is so great then American animators should work in that style. But I think it’s better for Japanese animators to work in the style that has developed there and, for example, Japanese anime didn’t try to imitate Disney style way back when and it’s developed it’s own story-telling and visual style, and that’s great. If America is developing the computer animation and that’s developing into a great thing, America should keep going in that direction. It’s good for the works to influence each other, but there’s no need for them to mix or intermingle.

Animation is a very long process. Do you find that as a creative person you get a backlog of ideas, and right in the middle of Paprika you come up with a new idea and you can’t wait to get to it? And if you do have a backlog, what are planning for next?

Creating a feature length animation is a lengthy process, and even if everything goes smoothly it can take two years. Really great ideas come up that I want to pursue, but you really have to focus on what you’re doing. As far as Paprika, we finished it last summer and I’ve had a lot to do in terms of promotion overseas and such. But there is an original film, an original idea, that I’ve wanted to do for a long time and that’s moving into the script process.