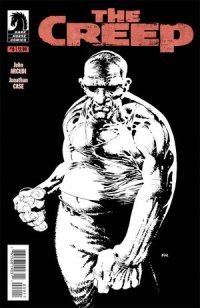

The Creep #0 ($2.99, Dark Horse)

by D.S. Randlett (@dsrandlett)

Over the past decade, with books like 100 Bullets and Criminal gaining popularity and influencing other, lesser titles, crime is slowly but surely becoming comics’ “other” genre. Sometimes it has a genre twist, so we end up with crime-horror, or crime-scifi. There are many other books that, if they are not overtly crime books, they have been at least greatly informed by the conventions of the genre. Something that almost all crime comics seek to draw upon is the noir element. It’s easy to see why: it’s a ready-made aesthetic with a certain deal of prestige cultural cache. So, when one sees a cover by Frank Miller depicting the deformed main character of a book called The Creep in his Sin City style, there are only so many things that you’re going to expect.

Once you open the cover, though, you’ll quickly find that The Creep is none of those things. What it is is a slow-burn mystery story that bristles with humanity. What you get is one of the year’s best comic books.

The titular “Creep” is a private detective named Oxel (the story seems to be set sometime in the 1980s), and like many in the fictional private eye profession his inbox isn’t exactly full to bursting. He has a disease called acromegaly, which doesn’t seem to cause him much pain, but it does make him look somewhat like a bruiser detective from a stylized noir. Of course, this isn’t a stylized noir, but rather a very tenderly drawn drama. In another genre, Oxel would hardly look out of place, but in this story his looks really make him stand out, and it really registers how it feels for him to be seen as a freak. Arcudi’s script really captures Oxel’s loneliness. One gets the sense that he took up the private eye business so that he could have people to talk to. The fact that the case that comes across his desk is a plea from his first (and, it’s implied, only) love twists the knife a little. It’s a story about an abnormal man whose past comes back to him, and with it maybe a chance to feel normal again, and it really registers.

The art by The Green River Killer artist Jonathan Case fits this story perfectly. It’s one of those rare cases where the comic book feels like the work of one person, leading to a sort of immersive flow in the story telling. Case goes for a sort of pseudo realism here, with enough of the real to keep the emotions grounded in something resembling the here and now, and enough of the cartoon to allow for maximum expression in his characters. This isn’t a heightened reality that we’re in: it’s a world of secret hurt and suburban disappointment, and Case gets that across beautifully.

Both a compelling mystery and a heartfelt examination of urban loneliness, The Creep is something that you simply must check out.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

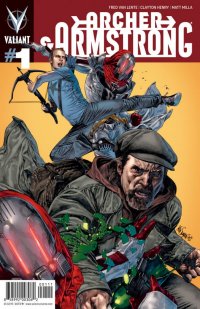

Archer and Armstrong #1 (Valiant, $3.99)

Archer and Armstrong #1 (Valiant, $3.99)

by Graig Kent

Searching through my now hazy memories of the comics of the 1990s I remember the original Archer & Armstrong being the best of the Valiant titles, or, at the very least, my hands-down favorite series within the line. It was the story of a tormented kid with serious parental issues named Obadiah Archer who joined a monastery to train in martial arts. Unable to let go of his rage towards his parents he was kicked out and wound up on the streets of New York fending for himself, until he encountered Armstrong, a 10,000 year old immortal who would have a hard time deciding whether drinking or fighting was his favorite thing. What resulted was a ripping, often poignant buddy-action-comedy from comics legend Barry Windsor Smith (and later Mikes Baron and Vosburg) that was cut down shortly after its second anniversary since, well, the entire Valiant line was collapsing like most of the industry at the time.

20 years after its original debut, Archer and Armstrong has returned, and, I have to say, it’s just as good, if not better than it ever was… if one can make such a claim based on just one issue and faulty memory. Writer Fred Van Lente has taken the original conceit and twisted it brilliantly for a modern audience. Obadiah Archer is still the child of an evangelical preachers, but now his parents are members of congress and owners of a creationist theme park. They’ve adopted almost two dozen children, all of whom are firmly indoctrinated in their cult-ish religion and rigorously trained in multiple fighting disciplines to take down a true child of satan, a 10,000 year old “man of sin”, referred to only in Voldemort-esque fashion as “he who is not to be named” (a point which pays off hilariously later on). The siblings compete for the honor of finding and destroying this “son of perdition”, and Obadiah wins out. He is provided the Fulcrum, a piece off an ancient weapon that “he who is not to be named” destroyed (but not before it obliterated most of civilization) that will guide Obadiah towards him.

When we meet the present-day Armstrong, he is as he should be, found hanging out in a bar, where, on occasion, he gets paid for stopping fights (when he’s not too caught up in them). When the two men meet, Armstrong is immediately tipped off by the Fulcrum what this naive kid’s misguided mission is, and proceeds to try and dismantle his world view while the kid tries kicking his ass.

Just like the original series, the chemistry of characters is rendered immediately, but I think I like the dynamic that Van Lente presents here even more so. That Archer is the product of a strict religious upbringing, as well as trained to be a warrior, and grew up cut off from the world in a propaganda-filled theme park with 22 siblings immediately makes him one of the more interesting characters introduced (reintroduced) in comics in recent years. I hope that Van Lente holds strong with Archer’s conservative fundamentalist background (which is equally funny and frightening) and doesn’t dismantle him too quickly as he opens his eyes to the lies he’s believed all his life. Armstrong is perhaps less slovenly than when Windsor Smith wrote and drew him, but feels relatively true to that original characterization, with some added elements to his history and distinguishing the mythos of the new Valiant eternal warriors very early on from that of 20 years ago. In some ways, Armstrong is a variation on another character Van Lente wrote for a lengthy period, Marvel’s Hercules, but he writes the excitable, hard-drinking immortal warrior archetype so well that it’s just a pleasure to read him playing with any variation of it.

The art from Clayton Henry is exceptionally clean, with strong lines and shadows. He’s good with details but uses them sparingly, leaving his exceptional figure work to stand out. Henry’s strongest trait his his physicality, the movement of his figures are both natural and dynamic, and he equally has a talent for faces and expressions, and they’re used to their maximum effect, especially in the comedic sense (emetophobes may wish to skip page 17, though).

Though Archer & Armstrong remains the only Valiant title to survive the recent purging of my comic book collection, my fondness for the characters was relatively faint. Consider it rekindled.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

It Girl! and the Atomics #1 (Image, $2.99)

By Jeb D.

Writer Jamie S. Rich has described this series as the Madman universe’s version of B.P.R.D.: a series of spinoff adventures centered on secondary cast members. That’s a daunting task, given the success of his model: Mike Mignola has carefully spent the past decade or so accommodating a wide range of writers’ and artists’ interpretations of his creations: if there isn’t already more Hellboy out there without Mignola’s participation than there is with him, I’m sure it’s just a matter of time. Too, Hellboy/B.P.R.D.‘s tropes of the horror/monster comic, and paranormal investigation, provide a time-honored story structure that is both basic and flexible enough for other creators to work with. But Mike Allred’s Madman defies that sort of thematic reduction: its wide-eyed psychedelic dreams of the Silver Age meet Hellboy’s gruff “Aw, shit!” with an awestruck “Oh, wow!”; think a less didactic Alan Moore, or a more bemused Grant Morrison. So striking off into a new direction requires balancing the impossibility of duplicating Allred’s specific vision, with the need to at least approximate it somehow. And the result is a mildly parodic comic that is… well, nice. Imagine something like Dan Slott’s Great Lakes Avengers, with less focus and fewer jokes.

Luna (It! Girl) is one of a loose team of super-powered folk associated with Frank (Madman) Einstein, who’s currently off touring outer space. In his absence, her life’s grown pretty dull, and she’s bored enough that her roommate Dorrie insists she put down the video games and get out of the house and go find some superheroing that needs doing. What she finds turns out to be an obvious inversion of typical low-level vigilante stuff; not even the dullest reader will fail to spot the mistaken conclusion she jumps to in trying to foil a robbery. What appeals about Madman isn’t simply ringing changes on vintage superhero clichés, but filtering them through Allred’s distinctive artistic vision; unfortunately, Rich doesn’t offer one of his own in its place. I kind of doubt that Rich shares Allred’s childlike affection for old-school superhero comics; he demonstrates familiarity with them, but no particular level of fondness. He seems to understand silliness without actually embracing it: when an old foe, trying to go straight, is “recruited” by his former gang of costumed super-criminals, Rich seems to feel that just giving them silly personas like ferrets and hedgehogs is enough of a punchline on its own, with no hint of an authorial wink or smile. It also doesn’t help that Luna’s opening fantasy segment goes on for several pages without a hint of anything like amusement, let alone any actual jokes; throughout, there’s a lot of setup without much payoff.

One of the perils of visiting the Madman-verse without Allred would be attempting to ape his visual style, and falling flat: Seth Fisher might have done it, or maybe Geoff Darrow, but even at that, you’d only get a surface resemblance; better, really, to take a wholly different approach, and artist Mike Norton does a very capable job. He begins with a classic superhero-batters-thugs-in-an-alley encounter, with It Girl looking like Ms. Marvel’s kid sister. It’s not much of a spoiler to say that this is not quite the reality of Luna’s superhero life, but, disappointingly, Norton doesn’t really play that up: his shift to the “real” world that the characters inhabit isn’t that drastic: Luna’s blond hair is a bit less long and flowing, the urban backgrounds are cleaner and more colorful, but otherwise, It! Girl and the Atomics inhabit a familiarly comic-booky universe, one that looks more what you’d expect from a well-made corporate Big 2 comic than one of Allred’s flights of fancy (and there’s more than a touch of irony that this comic is released just as Allred himself is getting back into Marvel work-for-hire again). Don’t get the wrong idea: for the most part, this book looks delightful, with lots of expressive faces, colorful costumes, and nice visual angles (colorist Alan Passalaqua is a real star here). But the script needed something off-the-wall to kick the book into overdrive, and the art really doesn’t supply that, particularly given the possibilities suggested by Luna’s living a fantasy life through video games. Again, Great Lakes Avengers is a good comparison: Paul Pelletier’s classically-styled superhero art worked because of Slott’s sly, subversive scripting; here, Norton is doing a perfectly straight job of illustrating a slightly-too-straight story. Madman fans and Norton completists will want to check it out; otherwise, I suggest waiting for Allred’s upcoming collaboration with Matt Fraction on FF.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Daredevil Annual #1 2012 (Marvel, $4.99)

Daredevil Annual #1 2012 (Marvel, $4.99)

By Jeb D.

So you’ve seen all the accolades and awards that Mark Waid’s current run on Daredevil is piling up, and you’re wondering if maybe this annual would be a good one-shot jumping-on point to see what’s up. Well, the short answer is “no”-Waid isn’t involved, and the story has no relation to the current Daredevil series. But that doesn’t mean I don’t recommend it-you just need to be looking for something a little different… and familiar, too.

Writer-artist Alan Davis is spending the summer of 2012 taking some of the cast of his cult favorite ClanDestine series on a little tour of pockets of the Marvel Universe. In last month’s Fantastic Four Annual, Ben Grimm, Johnny Storm, and Dr. Strange went on an entertaining time-traveling journey with the troubled Vincent Destine. This annual (and Wolverine, to follow) is a loose sort of sequel: Vincent’s wandering spirit now inhabits a mindless, unstoppable robotic “plastoid,” and naturally, Daredevil (again with the help of Dr. Strange) has a fisticuff-laced encounter with Dominic and Jasmine Destine before the plastoid problem is addressed.

Daredevil’s a tougher character to get a handle on than Ben and Johnny, though: one of the things that has made Waid’s run on Daredevil so effective is his ability to continue dealing with the residue of the wringer that Bendis and Brubaker put the character through, while not losing sight of the sheer fun of watching Matt Murdock bounce around Hell’s Kitchen, delivering punches, kicks, and billyclub mayhem. But, as is his wont, Davis blithely writes the character in pretty much the same way he would have twenty or thirty years ago; again, not a bad approach to the FF, but not addressing current continuity is awkward where Daredevil is concerned. And Davis’ love of the vintage days of 70’s Marvel comes with the odd whiff of fustiness: the police detective is drawn as a young Walter Matthau, while some incidental black characters of Haitian origin are presented in a… shall we say, “less than enlightened” manner.

Fortunately, Davis remains a brilliant visual storyteller (beyond the sheer aesthetic beauty of his work), and you’d have to go back to the heyday of Gene Colan to find an artist who so perfectly marries the darkness at the heart of the blind hero’s world with the sheer visual delight of superhero storytelling, with its blend of urban grit and rooftop exhilaration; here, Davis, longtime inker Mark Farmer, and colorist Javier Rodriguez, give a truly epic quality to the rather slight story. There’s also a glorious, extraneous, splash page, with Matt having a flashback that gives Davis an excuse to draw Elektra, Bullseye, Black Widow, Gladiator, Typhoid Mary, and a fistful of other familiar faces, without (sadly) actually including them in the story.

This is the first Davis book I’ve read in a while that I can’t endorse without reservation: the script is simply not up to the level of his best, certainly not a patch on the breezy fun of last month’s FF annual. But compared, say, with what his rough contemporary, Neal Adams, is offering these days, then just for the art alone, I’d say it’s five bucks better spent.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars