I figured that April would be

Grindhouse month, but mainstream audiences proved that’s not the case, and the

Weinstein Co’s beancounters agree. Still, if you loved the film there might be

a temptation to dig up some of the original films referenced so thoroughly by

Rodriguez and Tarantino. And digging through the grindhouse archives means that

sooner or later, you’re going to go home with a movie by Umberto Lenzi.

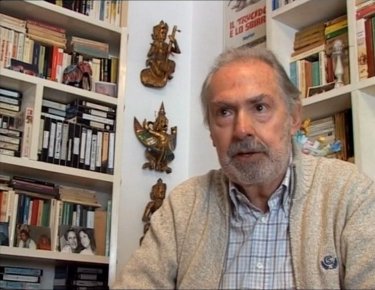

Jeremy ‘Mr. Beaks’ Smith referenced Lenzi in his excellent Grindhouse

review. What you didn’t see in that piece was a missing reel paragraph

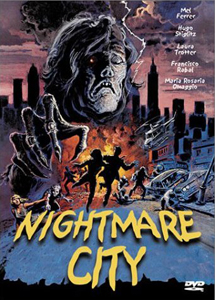

ridiculing Lenzi’s most commonly known film, Nightmare City. Not

to worry, Jeremy, I’ve got the trash talk covered here. With a little love

thrown in, too.

name that should inspire tremors of uncertainty. Bringing home a new Lenzi

flick is like picking up a girl with a bag over her head…you might unwrap a

Miss America stunner or a wildebeest. Or a wildebeest with poorly painted

makeup, decaying latex and visible hair netting. That’s more likely. Yeah, this

whole paragraph is sexist. But this is exploitation! Gotta set the mood.

Lenzi is famous for a

Lenzi is famous for a

couple of entries in the cannibal genre (like Cannibal Ferox, aka

Make Them Die Slowly, and Eaten Alive) but had his

hand in nearly every other pop movie mode between the ’60s and ’80s: spy

pictures, horror, giallo and crime. He claims to have invented the Italian

thriller with Orgasmo in 1969, which is patently absurd — there

was this guy named Mario Bava before him — and he hardly defined it as Dario

Argento did a year later with The Bird With The Crystal Plumage.

and skewed viewpoints are appropriate to his films. Looking at your average

Lenzi movie is like verifying your own appearance in a melting mirror. Nothing

feels right. People don’t behave like people, character is a distant

afterthought and physical laws might keep car tires planted on the ground, but

they don’t have any command over time and space. These movies either reveal the

process of a mind that is magnificently childlike in its lack of morality and

motivation, or truly deranged for exactly the same reasons.

average output, not

distinction between Lenzi’s inability to portray reality (or any version

thereof) and Lucio Fulci’s disinterest in doing so. Crucially, Lenzi almost

always lacks style, the presence of which in Fulci’s films lends a lot of

credence to his otherwise adrift stories. Watch any Lenzi horror movie and then

watch The Beyond, and the importance of style is obvious. And if

you haven’t watched The Beyond, why not? It’s glorious, and does face melting

as well as Spielberg.

Let’s start with Seven

Let’s start with Seven

Blood Stained Orchids, possibly one of the most unremarkable gialli in

existence. That is, once you factor out the attractive presences of Marisa Mell

(Danger: Diabolik) and Uschi Glas, in her single thriller

appearance most notable Italian appearance. Almost doggedly foregoing the visceral zeal with which Argento

dispatched females in his thrillers, Lenzi coughs up a list of seven women

about to get the axe. They’re nominally linked through their presence at a

resort hotel one fall, and more diabolically linked through the determination

with which a black-gloved pair of hands seeks to do them in.

justifiably revered for being hotbeds of experimentation, whether in content

(gore and sexual transgression), visual style or sound design. Orchids

boasts none of those indulgences. Riz Ortolani’s music is entertaining, but

there’s no theme strong enough to carry an audience through the interminably

long segments in which lead Antonio Sabato drives around looking for clues. The

set pieces are largely non-existent and the photography flat and drained of all

tension.

is tame and even yawn-inducing, relying only on nudity (not featuring Glas or Mel)

in the first act to keep the guys watching. In the long run, Uschi Glas makes

for a refined giallo heroine, in part because her perfectly sculptured hair is

so meticulously maintained. She’s never a mess. But that doesn’t make for very

interesting viewing, and even when she’s set up as bait for the elusive killer,

you won’t be held in suspense.

almost any typical form of Giallo titillation, the most damaging void in Orchids

is ideological. Lenzi’s most common theme is a distaste for the

lifestyle of the elite, and while that shows up dramatically in the two movies

I’ll talk about next, it’s barely a shadow here. The argument could be made

that Sabato’s mostly ineffectual ‘heroic’ presence is commentary enough (he’s a

famous and wealthy fashion designer) but since he doesn’t croak, I don’t buy

it. Beyond ‘hey, I like FPS killing!’ this movie has nothing

to say.

Two years later,

Two years later,

Lenzi would improve his cred slightly with Spasmo, which if not

nearly as sick as the title implies, at least keeps us off balance. Not only

does it string along a subjectively paranoid story in which the hero constantly

doubts his perceptions, it uses a strange sub-motif of violence against

mannequins to set an uneasy tone.

with a lady friend on the beach, Christian (Robert Hoffman) finds a woman

seemingly washed up dead on the sand. Barbara (Suzy Kendall) is actually alive,

and (to him) kind of sexy, so he tracks her to her boyfriend’s yacht and soon

the pair are hightailing it to her hotel. There, a man intrudes upon them and

is supposedly killed by Christian. That sets off a cat and mouse game of

murder, assumed identities, deceit and (not nearly enough) sex.

like a lot about Spasmo, which is the way Lenzi just breezes right through the

relationship between Christian and Barbara. It’s initially a one-night stand,

but Christian’s instability and Barbara’s apparent vulnerability merge to

create a co-dependent relationship that is almost a metaphor for something

larger

Here Lenzi’s distaste for the rich

gets more room to grow. Most of the film takes place in decadent, daylit

resorts and residences, where idle elites have the time and money to contrive

plots against one another. Eventually, we’re even told that the evil permeating

the film isn’t just located within the elite, but potentially stains the entire

class.

walks away from another woman without a word to begin a mercurial, meaningless

union with someone else, who might just be after him for his money.

George Romero was hired to shoot several minutes of gore to fill out the murder

scenes, which are mostly presented in one big flashback at the end. That

footage isn’t in the current DVD, or anywhere else I’ve been able to find.

Lenzi, in a supplemental interview, decries Romero for his involvement. I can

understand his point of view, but goddamn – extra Romero gore is extra Romero

gore, and I’ll never stop trying to track that stuff down.

pissed because he knows his movie is pretty tepid without the gore. Sure,

there’s an air of unpredictability to the storyline, but that’s due as much to

the fact that it makes no objective sense — the reveal of the mannequin

subplot throws all continuity to the wind — as to his ability to conjure up

the core of uncertainty within all of us.

So far you’re

So far you’re

thinking that Lenzi isn’t much worth consideration, but then, just maybe,

you’ll happen upon Almost Human. A crime flick in the very

classic Poliziotteschi mold, this is one of his best movies, and actually a

sick hardcore crime movie in general. Lenzi was at his best working on

euro-crime, and looking at Almost Human, you’d think the movie’s title

might even apply to Lenzi after all.

playing Giulio Sacchi, a cowardly sociopath who smothers his insecurities with

a full metal jacket. How’s that for a tagline? After being scorned by his

fellow gang members for panicking during a heist, Giulio concocts a scheme to

make half a billion Lire by ransoming a wealthy industrialist’s daughter. As

the scheme gathers momentum, he sheds all humanity, killing first impulsively,

then willfully and finally massacring nearly everyone he touches.

the camp bent that marked some of his comic and western roles, is nonetheless

as frightening a criminal here as you’ll find in the genre. He begins as a

simple empowered goof, much like Michael Moriarty in Q, but

sprints away from normal criminal acts so quickly that you can’t help but fear

him. Moriarty’s quirks are self-serving, but Milian’s are anti-social in every

possible sense. He’s a hair’s breadth from cashing it all in.

because Milian is ferocious, but also because Lenzi shares creative duties with

screenwriter Ernesto Gastaldi and cinematographer Frederico Zanni. Gastaldi,

also a jack of all genres, was much more attuned to the quirks of humanity than

his director. And Zanni captures real atmosphere in almost every frame,

something that Lenzi would otherwise assiduously scrub away. This movie is

dirty and full of suggestive shadows.

together not only on Eaten Alive, but on some of Lenzi’s other

good crime work: Rome Armed To The Teeth and The Cynic, The

Rat and The Fist. Look forward to coverage of those in one of the next

couple columns.)

Gastaldi, this film even packs some of the sexual deviance that should be highlighted

in Lenzi’s giallo output. There’s a constant threat of rape in any kidnapping

scenario, which isn’t downplayed here. But the real sexual attack occurs in a

Bunuel-esque scene, in which Giulio and his cohorts follow their quarry into a

rich villa. The occupants are having a typical rich folks’ night at home,

enjoying drinks and innuendo. After casually offing one of the villa’s elite,

another (male) guest is given the chance to live…if he orally services Giulio.

nasty enough, but it’s Milian’s face that pushes it into dementia. They’ve

barely begun their caper, and you can see that he’s already so far gone into

his power bender that he’s ready to commit any atrocity. And he does.

16mm blow-up car chase photography, the ever-present car going over a cliff and

Henry Silva as a determined cop. Fortunately the R1 DVD has both Italian and

English dialogue tracks, so you can listen to Milian’s original lines on the

Italian track and switch over for Silva’s dubbing of his own lines on the

other. Great stuff.

With at least one

With at least one

honestly decent movie out of the way, I can finally get to

people have heard of, and it’s one of the worst zombie films in existence,

which means that with a group of people it’s a fantastic way to kill 90

minutes.

starring alien invaders. Not a single frame of film is soiled by anything that

could be called human experience or response. It’s entertaining in the most

mind-altering way, because for ninety minutes you’ll try to figure out how

everything common to the lives of earthbound life has been stripped from the

film. You might even be tempted to call Lenzi a superb director; certainly even

Gilliam, Bunuel or Lynch never created such a fully formed alternate existence.

plane carrying a nuclear scientist makes an unscheduled landing at a big city

airport. Met by the Civil Defense Force, the hatch doors spew out fast moving

humans infected with latex and cake makeup. These Radioactive Face Zombies

(their makeup never goes below the jawline, except to occasionally affect the

hands) also spontaneously grow knives and hatchets, with which they quickly lay

waste to a bunch of guys carrying machine guns. I guess a Radioactive Face

Zombie can bring a knife to a gun fight. There’s an exception to every rule.

to the entire city, Lenzi’s directorial skills are demonstrably less developed

than a two month fetus. He doesn’t seem to care that Mexican main man Hugo

Stiglitz is barely coasting through his scenes, that the latex barely passes

for flesh, or that one scene leads to the next only because the inexorable

passage of time demands that it be so.

Don’t mistake my opinion, however.

that everyone can see that Resident Evil and the films of Uwe

Boll are by no means the depths to which genre can sink.

laughable gore, including the most prosthetic breast slicing since Anna Nicole’s

autopsy and the massacre of

dancers are magnificent. Just have some Fulci horror or Lenzi crime flicks on

hand to cleanse your palate afterwards.

Playlist

best thing about most of Lenzi’s movies is the music; represented here are two

Morricone scores, one Cipriani and one Riz Ortolani. Even if they’re not any composer’s

best, I’ll take them over almost anyone scoring today.

something else. As per Nick’s old Steady leak tactic (and early comics by Paul

Pope) I’m going to start listing what I listened to while writing each entry.

And since some future Videodromes (like the next one, if things go well) will

be focused around music in movies anyway, I figure I’ve got all the

justification I need.

Zombi

Zombi

Surface To Air / Cosmos

If the

Morricone/Goblin/Ortolani/Nicolai music in any given gialli has ever been more

entertaining than the movie it accompanies, this band is for you. Bass, drums

and synthesizer (primarily Korg and Prophet-600 for the geeks out there) are

harnessed into original tracks that will instantly write a better movie in your

mind than John Carpenter has made in 20 years.

http://www.myspace.com/zombi

Gamelan Into The Mink Supernatural

title, but Gamelan is my ideal combination of skilled playing and outsider

ethos. Massively heavy tunes that combine Echoplex guitar dones and boilingly

repetitive bass and drum rhythms. This is the space/psych record you always

wanted the Melvins to make.

(Currently touring with Zombi in support of the

inferior Trans Am. Definitely worth seeing.)

http://www.thepsychicparamount.com/

Grinderman

tendency towards simplicity that began with the last couple Bad Seeds albums

bears real fruit here. This is a short blast of fun for world-weary rockers.

Cave claims that his guitar sound here is pretty much exactly as it was when he

first plugged the thing in, and I love that; instead of hearing the endless

twiddling of knobs you’ll hear rough, ugly, fuzzy tones that are ideal for

Cave’s lyrics.

http://www.myspace.com/grinderman