The director’s cut DVD is often bullshit: a couple of extra scenes shoehorned in to a film that was perfectly fine, a way to sell a couple of extra discs. Every now and again a director’s cut emerges that is the real deal, though, a complete reworking of the original film. And sometimes those director’s cuts are much, much better than the original movie.

The director’s cut DVD is often bullshit: a couple of extra scenes shoehorned in to a film that was perfectly fine, a way to sell a couple of extra discs. Every now and again a director’s cut emerges that is the real deal, though, a complete reworking of the original film. And sometimes those director’s cuts are much, much better than the original movie.

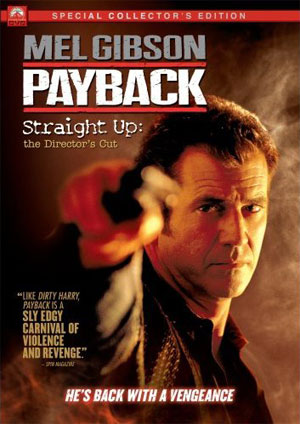

That’s the case with Payback: Straight Up – The Director’s Cut. This version of the film, out on DVD Tuesday, is a completely different experience from the original version that hit theaters in the 90s. Writer/director Brian Helgeland’s adaptation of Donald E. Westlake’s The Hunter was deemed a little too edgy by Paramount and star Mel Gibson’s production company, Icon. They wanted Helgeland to do reshoots to soften things up and add a happier ending, and the director refused. He was fired and about a third of the film was replaced with new material. All new characters were added, like Kris Kristofferson’s villain, as well as new story elements and a brand new ending. And in case you wanted more evidence of Mel Gibson’s S&M fetish, all of the torture scenes in the original were new – none of that stuff existed in Helgeland’s cut.

Now that Payback: Straight Up – The Director’s Cut is coming on DVD you’ll have a chance to compare and contrast the two films. It’s not a contest for me at all: the director’s cut is almost infinitely superior. I couldn’t believe how much more I liked that version. Click here to buy the DVD from CHUD. I really recommend it, even if you weren’t a fan of the original. Hell, especially if you weren’t a fan of the original.

Earlier in the week I got on the phone with Brian Helgeland to talk about the resurrection of his movie, as well as his troubled career as a director. He also spilled some beans on the proposed LA Confidential 2.

Watching some of the extra features, you seem to have a pretty good attitude about the situation with this film, but I imagine that you were pretty pissed off when this was all going down.

Yeah, but it’s one of those ‘time heals all wounds’ things. Enough water is under the bridge. But at the time, I had started out strictly as a screenwriter, and they have that old expression that screenwriters direct in self-defense. That was why I wanted to direct, because I thought this was the way to get what I wanted on screen completely, but then I figured out that could be the case but it wasn’t always the case. It’s funny – the Writer’s Guild moans and cries about it all the time and the Director’s Guild is smart enough to pretend that what ends up on the screen is 100% what the director wanted.

But yeah, it wasn’t good. I was going to get fired because I refused to do the reshoots, and my attitude was that if my father told me to do something I wouldn’t do it, so why should I do it for Paramount? I was nominated [for an Oscar] at the time for LA Confidential, and I remember thinking that if I could just win the Academy Award they might not have the nerve to fire me. And I ended up getting fired two days after I won.

What was the impetus for the director’s cut? Did they come to you?

I had a bootleg on a crappy VHS that wasn’t even my version so much as it was the last version I was trying to get past them before I was terminated. I had that, but it wasn’t really what I thought the film was. I wanted to do a version if I could only figure out with all the people involved how I could do it. But eventually all the people at Paramount left – they’re literally even out of the movie business, even – so it was really just Mel and me left. What I ended up doing was emailing him saying I wanted to put out my version of the movie but I needed his OK to do it. Fifteen minutes after emailing him I got an email back saying he thought it was a good idea and how he could he help. The next day he called Paramount and asked them to make the resources available to me to put this version out. I never discussed it with him, but judging by his actions I think he felt bad about how it all turned out. He stood by his decision, but he felt bad about the acrimony and how it turned out, so this was his way of trying to make up for that.

Why did you keep your name on the original cut?

I went to the Director’s Guild to find out about Alan Smithee-ing it, which they’re very reluctant to do. They have approval over whether you can Alan Smithee it or not. I had to meet with a panel over there and they very sensibly explained to me that if on my very first directing job I was Alan Smithee, my chances of having a second directing job were going to be very difficult. So I kept my name on it, apparently having done more footage than some directors who happily keep their name on a film. I just thought it was kind of cutting off my nose to spite my face.

What’s your status as a director now? It’s been four years since your last film.

I had a similar experience on the film I did with Fox last, The Order. A lot of meddling, a lot of not wanting to release the film the way I did it until I sort of pumped up the special effects and reshot the beginning. I’m just a little tired of it. I’m a little tired of it, but I just wrote something that I’m going to try to direct. Not that I’m so delicate, but it takes a lot out of me and when it goes wrong… well, I’d rather play basketball. I get more satisfaction out of basketball.

Your first film was a crime movie. I’m not quite sure what genre I would place A Knight’s Tale in…

Which I actually made wanting to have a lot of fun and make a movie that was fun to do after my Payback experience. You had to be noble to joust was the idea. Doing a story about peasant who wants to be noble so he can compete is a bit like a screenwriter wanting to direct. The script I’ve written that I want to direct is called Get Up, Sonny Liston. It’s a romance first and a thriller second; I’m just trying to get that going now. It’s not a boxing movie.

There have been so many rumors about LA Confidential 2. Are any of them true?

I don’t know if that’s going to happen or not. Curtis [Hanson] myself and James Ellroy have been talking about different scenarios, but just a little bit, just kicking it around. I don’t think we’ve found anything yet that we thought was good enough to merit a sequel.

Whatever happened to your Moby Dick?

I need to get a hundred million dollars so I can get that off the ground. It’s just kind of out there.

Were you able to find all the footage you needed for this director’s cut?

Just about. There was some footage that the trailer department lost – actually I think the Warner Bros trailer department. There are a few shots where the negative got cut and some frames were missing so I couldn’t use some takes, but 95% of what I needed was there.

I thought it was really interesting that you guys couldn’t use an Avid to edit this, that you had to do it the old fashioned way.

I had never cut on film except for Super 8 films I had made. I’m not a big fan of it only because it takes so long to do different things. On the Avid you can compare different takes easily and you can’t do that on film. Everything takes so long and I don’t think I needed more perspective on it after all the time that had gone by! In some ways you have to think about what you’re doing because it takes so long to undo it, but in some ways it might limit what you can do because it does take so long to do it.

Have your experiences made you more cynical in general about Hollywood?

Not cynical but more understanding about how things work. It’s be hard to find a film out there that’s completely 100% what the director wanted it to be, and the more money of theirs you spend the less chance you have of putting out a film that is what you want it to be. You’re obligated to so many financial pressures that it’s impossible.

When you’re working as a screenwriter are you the kind of person who hands in the draft and moves on or do you fight to stay involved?

Scripts are like children – you don’t want to have someone else raise them. I stay on as long as I can, but that’s at the discretion of the director. So far I’ve been lucky: with Richard Donner I was onboard the whole way through Assassins, and the film I did with Tony Scott [Man on Fire] I was on the whole way, my Clint Eastwood movies I was on the whole way, LA Confidential I was there all through shooting. I’ve been lucky that way. Of all the screenwriters I know, I’ve been on the set and been with the project from start to finish the most.

There’s a lot of talk on the special features that the studio and Icon felt that maybe audiences didn’t want the kind of movie you had made with Payback. Besides being a weird thing to say because they saw the script, do you believe that?

No, I don’t think so at all. I think 300 is a good example in that the hero dies at the end. I think it’s the testing that has gotten them to so second guess everything and to feel like they have this insight into the mathematics of what audiences want. I’ve always maintained that the audience is a lot smarter than the executives are, and a lot more willing to go with a filmmaker than executives are. The sad thing is that people want to take away the mystery of film. William Goldman’s ‘Nobody knows anything’ is the truest thing and everybody quotes it… with a ‘but’ at the end. ‘But I kind of know what the audience wants.’ The micromanaging of film and trying to anticipate what’s going to sell – it’s that corporate thinking, which goes with corporations buying up all the studios. There are a lot of movies out there that never got made or were never conceived because of all that.