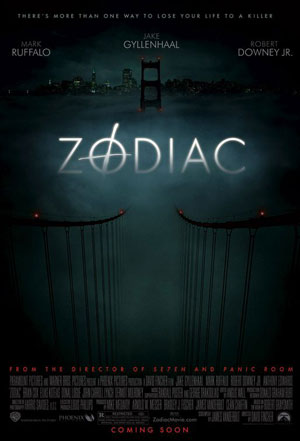

Zodiac is journalism. Zodiac is a David Fincher movie unlike any other David Fincher movie. Zodiac feels a lot like a masterpiece.

Zodiac is journalism. Zodiac is a David Fincher movie unlike any other David Fincher movie. Zodiac feels a lot like a masterpiece.

David Fincher’s feature career, with the exception of the disastrous Alien 3, is filled with gimmick films. He uses visual gimmicks, and he often uses storytelling gimmicks. As individual experiences, these gimmick movies can be exhilarating, but after a while that exhilaration wears off, leaving…. what? For me the act of revisiting a Fincher film is often a surface pleasure only; The Game has little to offer on multiple viewings, while Seven is reduced to mostly atmosphere. Panic Room is too bloated to be the down and dirty movie it’s supposed to be, and the misguided fanboys have tainted Fight Club so much that I need another decade before I can be fair to it.

Zodiac has so little in common with these films that it feels like the product of another filmmaker. It’s a major turning point in Fincher’s career, a movie that announces that the director is done dazzling us or tricking us. Where other Fincher movies grabbed your attention like a shiny object, Zodiac is like quicksand, inexorably drawing you deeper and deeper into itself. The movie is about obsession, and I predict it’s a film that will become an obsession for many.

But how many? Box office prediction has no place in a real movie review, but it’s worth noting that Zodiac is defiantly uncommercial. Not only has Fincher seemingly eschewed almost all of his visual tricks, he’s dared to make a serial killer movie in which the killer is not caught… and in fact where the killings stop halfway through. The moments that stand out from Seven are the crime scenes, but Zodiac treats the killings in almost matter-of-fact way. We see them, but rather than horror show sequences they feel like very mannered reenactments of police reports. Which, in many ways, they are.

Fincher has achieved many incredible things in Zodiac, but one of the most amazing is the air of authenticity he has created. I have been growing weary of 60s/70s period pieces that are nothing more than bad wigs and ugly clothes, as if every person in America suddenly lost their fashion sense in those years. Fincher dresses his characters like people – the fashions of the times are reflected, but where most films set in the period feel like the costume designer only looked at the worst pictures from a 1972 wedding, Zodiac feels like its of the time. Every detail is flawless, and most of them are invisible. Fincher isn’t drawing your attention to the period detail, but it’s there. It’s everywhere, nestled in the corners of every shot, quietly enforcing the reality of the setting.

That eye for detail really focuses on the aspects of the Zodiac case. Walking into the film I knew very basic, very sketchy things about the killings. Walking out of the film I felt like I had just read a book on the case. The only film I can compare Zodiac to in this regard is Oliver Stone’s JFK, but that’s just in the presentation of information, not in style. Like Stone with JFK, Fincher finds his own way to give us the mountains of information without turning his film into a boring expositionfest. For Stone the way to do that was with a kinetic, inventive visual style. Fincher has chosen a more conventional style, though, so he uses damn fine storytelling to keep us involved. And then, along the way, he trusts in the details themselves, knowing that we’ll get slowly more and more obsessed with them, just as the characters are on screen.

The movie opens with a Zodiac shooting but quickly moves on to its true subject, Jake Gyllenhaal as Robert Graysmith, a cartoonist at the San Francisco Chronicle. Fincher is known for his title sequences, and Zodiac’s could be the best yet… even though most of it is about the delivery of mail. Fincher connects the Zodiac with the Chronicle by following a letter from the killer to the newspaper as it works its way through the system, set to a driving Santana song. It’s the most exciting mail delivery sequence in motion picture history, I believe.

Graysmith happens to be in the editorial meeting where the first Zodiac letter is read; the killer has included a cypher and a demand that it be printed on the front page of the paper, otherwise he’ll go on a killing spree. Flamboyant and hard living crime reporter Paul Avery (Robert Downey Jr in yet another goddamn amazing performance. When is this guy going to be recognized as one of the greatest living actors?) gets assigned the story, but Graysmith becomes fascinated by the code – he’s a puzzle freak. In what begins a long history of civilian involvement in the case, the code is cracked by armchair sleuths who see it in the paper, but the deciphered message brings more questions. The Zodiac case begins to grip the public imagination, and when he kills a cabbie in San Francisco, Dave Toschi – the inspiration for Bullitt – and his partner William Armstrong (Anthony Edwards, completely redeeming the last few years of his career with this one supporting role) get assigned to investigate. Graysmith, Avery and Toschi are the three men who the film revolves around, as the case slowly consumes them.

Mark Ruffalo plays Dave Toschi, and at first his performance feels like a caricature – his Toschi has a Columbo feel to him, and an overplayed fondness for animal crackers – but over time what felt like an affectation becomes ineffably real. Ruffalo immerses himself so deeply into Toschi that after a while it stops feeling like acting, which means that no one will end up paying much attention to it. Audiences and critics sit up and notice when an actor ACTS, but they never seem to realize when real acting happens, when an actor just submerges himself completely into a character.

Downey doesn’t submerge himself into Avery, but you suspect that it’s because the man and the actor have a lot in common. Robert Downey Jr is the kind of actor who doesn’t need the best written lines to have the best lines in a movie; he has a way of delivering lines that makes them instantly pithy classics. Thankfully he’s given well-written lines in Zodiac, so that when he delivers them so well they truly sing. I like the way that Downey approaches Avery, not feeling the need to make the man into a hero, being comfortable with having him just be really good at what he does.

The weak link in the picture, sadly, is the lead. Graysmith’s story is one of a descent into a consuming obsession; long after the police have essentially given up on ever catching Zodiac (only Toschi remains on the case after years of fruitless leads) and the public has lost interest in the inactive killer, Graysmith takes it upon himself to keep looking for clues. His inability to let Zodiac go destroys his marriage and costs him his job, and his downward spiral is a juicy arc that any actor would kill for. Unfortunately Gyllenhaal can’t make it real. He’s a great choice to play the Graysmith of the first two acts, the guy who is very into the case but hasn’t yet let it consume him, but he can’t make us believe in him during the scenes where Graysmith is home alone amidst piles of boxes or obsessively pounding on a police station door in the middle of the night, trying to get one look at an important document.

Thankfully everything else is strong enough to make up for Gyllenhaal, and by the time Zodiac gets to a point where his character is going places that he can’t get to as an actor, we’re already completely absorbed in the case. By the third act we’re just as into the mystery as the characters are.

Zodiac runs for two hours and forty minutes; I sat rapt for every second of it. Television has made the police procedural into a small screen, formulaic affair, but Fincher recaptures it for the cinema here. Technically, Zodiac doesn’t feature anything you couldn’t see in a cop or other crime solver show (and honestly, a crime solving political cartoonist isn’t a bad hook for a TV show), but Fincher’s movie is sweepingly cinematic, a widescreen spectacle without action. In fact, Fincher makes the movie utterly gripping and tense without putting his characters into any thriller scenarios – with one huge exception, a scene featuring Charles Fleischer that is almost unbearable in its intensity.

The characters in Zodiac slowly fall apart because of their obsession with the case. It’s public record that no one was ever convicted for the crimes, but Graysmith, who wrote the books that form the basic skeleton of this film, believes that he finds his man. Zodiac is sort of a love letter to obsession, and knowing what a driven perfectionist of a filmmaker Fincher is, it’s not surprising that this would be how he views the subject. Obsession is damaging, it can destroy you… but it’s worth it. And it’s very interesting that the Zodiac case itself contains some strange and unexpected film-related elements, and that the entire movie could be viewed metaphorically as the obsessive attempt to capture something that can never quite be caught – the filmmaker’s essential dilemma.