Southerners make the best storytellers. Craig Brewer is one of those storytellers. This interview happened in an office in Midtown Manhattan on one of the coldest days of the year, but the feeling was like sitting on a front porch in the Southern summer heat, drinking beers.

Southerners make the best storytellers. Craig Brewer is one of those storytellers. This interview happened in an office in Midtown Manhattan on one of the coldest days of the year, but the feeling was like sitting on a front porch in the Southern summer heat, drinking beers.

Black Snake Moan is Brewer’s third film. His last was the excellent Hustle & Flow, which finally launched Terence Howard to stardom and made history by winning a gangsta rap group an Oscar. His first film was the very little-seen The Poor and Hungry, a black and white feature made for a few thousand dollars he got when his dad passed away. All three films are soaked in Southern attitude and baked in Southern heat, creating the kind of regional cinema that has felt dead in the age of megacorporate moviemaking. In fact, I feel like Brewer’s only real contemporary is David Gordon Green, another filmmaker whose movies have an ineffable sense of Southern place.

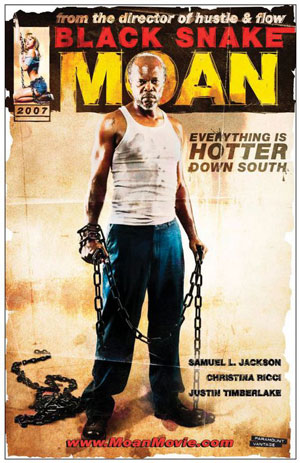

Black Snake Moan is a strange, and sometimes difficult film, but an incredibly rewarding one. Christina Ricci is a wild child nymphomaniac named Rae, who is raped and beaten and left for dead by the side of the road. Samuel L Jackson is Lazarus, a recently divorced old bluesman who finds the white girl, brings her home and chains her to a radiator to help her get the devils out of her. And like Hustle & Flow, Black Snake Moan is a movie that doesn’t just talk about the redemptive power of music – it redeems you with it.

Black Snake Moan opens this Friday.

You take on interesting racial and sexual politics in this film. Are you expecting people to just see the image of the woman chained to a radiator and not look beyond that?

Do you mean on the poster or going to see the movie?

Just the ads, the poster, the trailer.

I don’t know. First of all, I’m very much part of this marketing campaign; this isn’t just a studio trying to sell this. And I don’t think anyone who can’t get past [the campaign] doesn’t need to see the film. However I’m hoping that credibility of Hustle & Flow… now a lot of people are seeing it because of DVD and because of online who originally said, ‘I’m not into rap, I’m not into pimping,’ who have come up to me and said the movie was about more than they thought.

This is my most moral movie. I’m a filmmaker from the Red States and I’m really coming at the South with my thought of what being a person of faith should be. And that means a lot of patience and a lot of unconditional love – even if that means going about it in a rather unorthodox way! But I don’t know if people are going to stop when they see the black man and the white girl, because I think as much as people are terrified about that, they are incredibly titillated by it, and nobody wants to talk about that. I’m not doing a movie where I’m exploring race or where I’m exploring gender – it’s there for people to experience without me commenting on it. But what people aren’t talking about is that imagery and, because of whatever reason, it’s taboo and we’re attracted to it. We get a reaction from it.

It’s interesting that you say that this is your most moral film, because this movie seems to live in a place similar to the drive-in rednecksploitation films. But what people miss today when they go for that exploitation feel is that, in their own way, many of those films were very weirdly moral. Evildoers were punished. When you began this picture, there was some confusion about I Spit On Your Grave –

Yeah, I mentioned that to Harry [Knowles] and I think it got a little bit out of control. I was thinking of the aesthetic of I Spit On Your Grave, or Gator Bait, for Rae. If you look at even the poster of I Spit On Your Grave with the dirty cotton panties, that’s what I was explaining.

But I did not, to be honest with you, make this movie to be a race bating exploitation picture. As much as I think there’s a resurgence of that kind of stuff with Carnahan and what Quentin and Robert Rodriguez are doing, and while we have a love and respect for those kinds of movies, I wasn’t thinking of that when I was writing this movie or even when I was making it. It’s hard for Hustle & Flow not to look like Truck Turner when I’m shooting in Memphis with that particular kind of language and that particular kind of soul music behind it. This movie, with its humidity and the sexual tension, was much more inspired by the works of Flannery O’Connor, Tennessee Williams – especially a movie by the name of Baby Doll, which not many people have seen. It’s got Carroll Baker sleeping on this crib and Karl Malden is her husband and he’s waiting for her to turn 21 so he can fuck her. The Catholic Church banned it, said you were going to hell if you saw it. I’m much more into the melodrama for this movie, because it comes from the blues.

The New York Times recently called you the Fellini of Memphis. I can see that, but I also feel like you’re the Martin Scorsese of Memphis, where music is your crime. Obviously this comes from the blues – there’s a blues song in the title – but how does music affect the way you approach a movie?

I don’t sit down and go, ‘Ooh, this would be a great story.’ That’s not how it works with me. For a long time it used to be that way, but what it led to was a lot of cynicism. You start off in filmmaking when you’re not in film school or in Hollywood and you want to go off and make a film on video, you start off with cynicism. And you start off with analysis. You’re saying, ‘Well this movie sucked because of this, and if they just did this…’ So you write scripts where you think the story will be so great that people are going to have to make this movie.

When I moved to Memphis full-time, about 13 years ago, and I really committed to Memphis and to the musicians of Memphis and to hanging out with the people who recorded the greats, things changed. Where they changed was I would listen to the music and I would just kind of zone out. Whether that means I was with some friends and drinking or smoking of whatever, but images would come to me. And when these images would come to me I would then turn into a detective a little more. What was happening with that image? With Hustle & Flow I could roll around Memphis listening to Three Six Mafia and 8Ball and MJG and roll down Vance Avenue heading towards downtown, and I could see it. I could see a desperate family that had come together because of their squalor and their, let’s be honest, life of crime, and they wanted to do one pure thing. They wanted to make music.

With the blues, they day it finds you, and I really felt the blues found me. I fell in love with the blues when I saw Risky Business and it was Tom Cruise with the Ray-Bans and the music behind him was Muddy Waters’ Mannish Boy off the Hard Again album, and that was the first album – I think I was 13 when it came out, and I had to get that album.

That’s such a white boy way to get into the blues!

It is such a white boy way. You know, the only way to get into blues these days is the white boy way. African-American young culture needs to embrace the blues a little bit more otherwise it’s just a bunch of white intellectual college boys that are into it. But I came at it as this is from Memphis, Tennessee, or this is from the South. I always collected things of the South, like short stories – even the painting, Southern Cross the Dog is over the couch the whole thing. Photography of William Eggleston…

It is such a white boy way. You know, the only way to get into blues these days is the white boy way. African-American young culture needs to embrace the blues a little bit more otherwise it’s just a bunch of white intellectual college boys that are into it. But I came at it as this is from Memphis, Tennessee, or this is from the South. I always collected things of the South, like short stories – even the painting, Southern Cross the Dog is over the couch the whole thing. Photography of William Eggleston…

But anyway, I was having these bad anxiety attacks when I was getting Hustle & Flow going. I never had them before, but then my dad of a heart attack at 49, completely unexpectedly. A healthy guy, never drank, never smoked, and then – bam – dead. It really began to mess with me, and that’s when I felt like the blues found me again. I was zoning one night, listening to some Skip James, and this anxiousness came over me again. I don’t know if you’ve had them or know people who have had them, but they’re very random, but your mind can trigger them if you feel them just a little bit. If you start obsessing about it you release this adrenaline rush into your body and you’re just fucked.

Well, one night I saw this image while I was listening to Skip James singing Hard Time Killing Floor Blues. I was going through the front door of my granddad’s house in the woods and there was a radiator there, and a chain around it. This coiled chain that was coming uncoiled and was just zipping past me as I was coming in on this radiator, and the anxiety was building and building and building in me. I was like, ‘Pull out! Stop thinking about this!’ And then it went tight against the radiator and it clanked and the radiator just held and I saw this chain just keep yanking against the radiator and dust flying off of it. And then my panic attack stopped. I didn’t know what that image was, but it fascinated me, and I just couldn’t picture it without playing some blues. So I started playing all the blues that I had in one night and I saw this whole tale about me as this… crazy young sexy white girl! [laughs] But I felt like at that moment in my life I needed some no-nonsense old man sense, someone to just say, ‘Calm down.’ And it needed to come to me not from a place of righteousness or judgment, it needed to come from a place of, ‘No, it’s OK, we all fuck up. We all get drunk, we all fall into the wrong beds once in a while. Keep going, you’re alright.’ I think I needed to hear this, and that’s how the tale came about.

The elements of exploitation, I think, are more functional than ornamental. It’s important with this movie that the audience feel a little conflicted with their lust for her. It’s important that they feel conflicted with, ‘Are they gonna fuck? Is he gonna screw her?’ People both terrified and titillated at the prospect of these two people being in the same room together.

You have the terror and titillation, but you also have Samuel L Jackson as the black guy. Frankly speaking, there may not be many safer black guys in American culture today. Everybody loves him.

He’s earned our friendship. We love anything Sam’s going to be in. He can be in a bad movie and when he comes on the screen, you can hear the audience sigh.

Did you cast him on purpose for that comfort level?

No. He got the script through Singleton and he was so passionate about wanting to play it. First of all, it’s Samuel L Jackson, of course I fucking want to do something with him. But more and more I felt the safety in the Southern numbers. I liked that he grew up in Chattanooga Tennessee, and that he had experienced pain in his life, and that he had put it behind him. This is a character who put pain behind him and is suffering because he lost an important part of himself. And to me that part of himself is like an exorcist. What I mean by that is that I think bluesmen are exorcists. Rappers are exorcists. You go to these clubs not wanting to kill people or get into a fight or roll up against some hot girl and put your hands on her, but you’re hearing it in the music. You’re chanting to it, responding it, you’re sweating and you’re singing and your voice is hoarse and your ears are ringing and you go home and you sleep. To me, that’s what folk artists would do. Bob Dylan did the same thing in the streets of New York. He was taking Woody Guthrie songs that were about pain and people would get to feel it in the coffee shops… and then go back to their rather affluent lives and feel better about themselves! [laughs]

You talk about collecting things that are Southern. I’m a Brooklyn boy, but I’m deeply fascinated by the South. The Drive-by Truckers talk about “the duality of the Southern thing.” As a progressive white guy, what does all that mean to you?

A couple of things. Intense passion with crippling insecurity. We open our mouths and immediately think we’re being judged. We open our mouths and many times we are, but we use that to our advantage. Let me give you a New York connection: my grandfather was a famous baseball player. He could have run for mayor of New York and won. His name was Marvelous Marvin Throneberry, played for the Yankees. He played for the worst team ever, the ’62 Mets under Casey Stengle. New York reporters would delight in calling him a dumb hick, and where Marv could have crumbled, he realized y’all can’t make fun of me better than me. That’s when they started to love him. He’d triple, he’d forget to hit second base, he’d say things like, ‘I just can’t count that high.’ It’d be Casey Stengle’s birthday and he’d say, ‘You know, Casey, I wanted to bring in the cake but they were afraid I’d drop it.’ Dolly Parton does the same thing – ‘It costs a lot for me to dress this cheap.’ She’s beating you to the punch and she’s letting you in on her vulnerability, and that makes us stronger.

I think people respond to that rebel flavor. They may not respond to the Confederacy – not that everybody in the South responds to the Confederacy. There is a sense that we all lost. As much as I know, and I would never to condescend to say that African-Americans didn’t win something at the end of the Civil War, but if you go to a lot of Southern blacks in Mississippi after that time period, they sure didn’t feel like winners. And they had to sing about it. They had to sing about injustice. Those original bluesmen were the true pioneers of expressing the fear. To me, that’s the Southern spirit – you don’t have much and you do a whole lot with it.

The South is the Mesopotamia of American music, and it all came from poverty, it all came from those collisions of race, of culture, of gender. We’re a better country because of the South.

Maggie Lynn is next?

Maggie Lynn is the outlaw country music movie.

Do you have a cast?

Not yet. It’s all done, and we’re meeting about it and we’re going to be casting after I finish opening up this movie.

Are you comfortable being the music guy?

For right now I am. I put a lot of time and heart into it, and it’s rewarded me. I like it. I can’t wait to tell my soul movie – I’ve been dying to tell the story of the sanitation strike and Stax in Memphis, Tennessee. There’s a very special time in our history when Otis Redding went down in a plane crash in December of 1967 and then Dr. King came to town for the sanitation strike and then was assassinated in 1968. So, there’s a good five months there that I think is when music really began to change.

And you and Terrence Howard are working together again?

Yeah, we’re getting a writer for the Charlie Pride project.

That’s a fascinating story because of the intersection of culture and race and music – he’s the black country singer who sold a ton of records but nobody knows who he is.

It’s a true shame. He’s one of the most successful entertainers of all time and you read a list of the top 100 African-American success stories and they never mention Charlie Pride. People call him the Jackie Robinson of country music, and I always say, ‘Yeah, but a flood of talent came after Jackie Robinson. Who came after Charlie Pride?’ He’s such a unique individual and such a great love story with him and his wife Roseen. And it’s going to be interesting to see an American patriot in the form of black man during the Civil Rights movement singing country music. It’s the true definition of what freedom is, in that no matter what color your skin is you should be able to have the right to tackle whatever you want and to be whatever you want to be.

Why do you think he’s ignored like that? Why doesn’t he make the lists?

It’s why the blues are ignored. You have to look at it in a historical context. Blues music is very much about how they’re in a sorry state and the Civil Rights movement came around and they didn’t want to embrace that music – they needed gospel, they needed soul. So to see a black man singing this – back in the day this wasn’t such a pejorative word – this cracker music… he’s been called an Uncle Tom by many people even thought he is a country boy from Sledge, Mississippi who was raised on the music, who has a better voice and a better understanding of country music than scores of white people of the region. The people of the region saw that for him – they embraced him.

Were you surprised by the Oscar for Three Six Mafia?

When they got the nomination I was delighted and completely confident we would get the Oscar.

Why were you so confident?

Because if that song got nominated, it means the song couldn’t get out of Academy voters minds. Because of the way it was constructed, because the audience – who might not like rap – was there when it was created, it was a functional song. It wasn’t ornamental. It wasn’t some montage, it wasn’t over a closing credits. People watched that song get built right in front of them, and they watched the characters delight in the act of creation, thereby exciting the audience as they watch it being created. I just think that the Academy couldn’t ignore how catchy that song was and how important to the movie it was. It was what a Best Song should be.

[This next question is, in a very general way, a spoiler for the end of Black Snake Moan. You will not learn the actual ending, but you will find out the tone of the ending. Be warned.]

Your two major films, Hustle & Flow and Black Snake Moan, have these fairly happy endings. They have darker, rougher elements, but they end on happy notes. Is that important to you as a filmmaker?

It is. I’m much more inspired by Ford and Capra than people would like to believe. I think the difficulty is that they see the authentic settings, and they hear the authentic accents and they think, ‘Well, we must have something dreary if it’s that authentic.’ I live in that place. The accents and the locations and the milieu are not unique to me, nor novel. I believe music does inspire. I lived the dream of DeeJay, I did make music in my house and I did rally together drug dealers and pimps and strippers, bouncers and prostitutes to make my first black and white movie, and they wanted it to be good. They didn’t want it just to be fluffy and funny. They wanted it to be real. And they’re all coming to my premiere in Memphis next week on the red carpet. If anybody looks at Hustle & Flow and thinks it’s unrealistic, come to Memphis next week and we’ll all smile and wave. But definitely with Black Snake Moan I did experience a happy ending. I did experience that happy ending when I was losing my mind and losing control of my body with these attacks, I found that happy ending when I let go of some fear and moreso let go of some hate, I found that happy ending when I shook people’s hands and looked them in the eye and especially amongst my friends let them know that I love them and that if they’re having problems they shouldn’t get down on themselves… I believe it. I truly believe it. And I think we need more of it now.