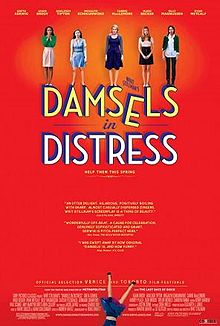

In 1990 Whit Stillman burst onto the burgeoning ‘indie’ scene with Metropolitan, for which he very deservedly received an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay. While in a broad sense Stillman can be lumped in with other 90’s post-Woody Allen ‘East Coast talkie’ independent filmmakers, focusing on dialogue far more than concept or story, Stillman was creating a style unto himself — an affected comedy of manners exploring disconnected, eccentric, and often malcontent upper-class youth. He completed a trilogy of films within this world, Barcelona (1994), and The Last Days of Disco (1998), spawning now famous disciples like Wes Anderson and Noah Baumbach (whose first film Kicking and Screaming even featured Stillman regular Chris Eigeman). And then Stillman up and disappeared from the cinema landscape. Now Stillman has finally returned to us – refreshed or re-inspired or whatever it was that kept him away – with his first film in thirteen years, Damsels in Distress.

In 1990 Whit Stillman burst onto the burgeoning ‘indie’ scene with Metropolitan, for which he very deservedly received an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay. While in a broad sense Stillman can be lumped in with other 90’s post-Woody Allen ‘East Coast talkie’ independent filmmakers, focusing on dialogue far more than concept or story, Stillman was creating a style unto himself — an affected comedy of manners exploring disconnected, eccentric, and often malcontent upper-class youth. He completed a trilogy of films within this world, Barcelona (1994), and The Last Days of Disco (1998), spawning now famous disciples like Wes Anderson and Noah Baumbach (whose first film Kicking and Screaming even featured Stillman regular Chris Eigeman). And then Stillman up and disappeared from the cinema landscape. Now Stillman has finally returned to us – refreshed or re-inspired or whatever it was that kept him away – with his first film in thirteen years, Damsels in Distress.

So was it worth the wait? No, sadly not really. But I am extremely glad Stillman is back in the mix. Damsels is an uneven movie, with a disappointingly 60/40 success-to-failure joke ratio, but the jokes that land, land hard, and the film itself is a winningly pleasant experience that allows for the failed comedy to come off more as dead space than actually unfunny.

As with all Stillman films, the setting is of far greater significance than the plot. Damsels takes place in a slanted college campus reality, at once modern yet trapped somewhere in the 60/70’s when all-male schools where shifting into coeducation. A trio of gorgeous and do-gooder girls, Violet Wister (Greta Gerwig), Rose (Megalyn Echikunwoke) and Heather (Carrie MacLemore), have appointed themselves the philosophical arbiters of Seven Oaks College. Violet, the leader, believes that women should date down, because stupid men need their help. She believes the power of certain tasteful aromas will alter a person’s self worth. She believes that dance is the best solution to suicidal depression. And she also believes that creating a new dance craze is one of the most important contributions a person can make to society and history; far more relevant than becoming president or writing a book. During New Student Orientation, Violet spots Lily (Crazy Stupid Love‘s Analeigh Tipton), and immediately takes Lily under her wing, making her the fourth member of the group. Lily is a character from our real world, who is both fascinated by and slightly perplexed by the Stillman-y Violet. And the two influence each other. The girls’ lives become complicated by the affections and rejections of three men, smooth businessman Charlie (Adam Brody), sexy intellectual grad student Xavier (Hugo Becker), and Violet’s borderline retarded boyfriend, Frank (Ryan Metcalf).

Stillman’s films – especially Barcelona – have always meandered in tone, but Damsels is all over the place thematically and structurally too. The movie begins abruptly and unclearly, tossing us right in with the nutty characters before we have any greater sense of the atmosphere. Violet’s trio are highly stylized creations. Lily on the other hand at first feels like a normal person from a normal movie. Things appear to be a Stillman-esque tweak on the Meangirls dynamic, with Lily being a fish out of water getting pulled into a specialized click. But this dichotomy ultimately proves meaningless as the film progresses and we discover that all the characters are stylized creations who function and rationalize on a gradating scale of quirky weirdness. So it is hard to infer what Stillman is going for, particularly because at no point is Seven Oaks presented as a special case, a school known for its bizarre students. Eventually we have to conclude that this is simply the way the word is, as with any Wes Andersen or Quentin Tarantino heightened reality — this is just how people talk and rationalize. Giving Stillman the benefit of the doubt, this leaves Damsels meant to be a satire on college and education themselves. But really there is very little commentary here, aside from simply using the setting as a natural place to conjoin a variety of characters with idiosyncratic world views.

In the 90’s Stillman had a great knack for biting social representation, which mingled interestingly with his fascination for characters who espouse strange causes and philosophies. Like Tarantino, Stillman could craft masterful conversations, and had a passion for scenes involving one character explaining something to another character. Damsels has this. Violet is a fountain of espousing. But the dialogue lacks the bite and purpose Stillman used to have. Maybe part of this is just me — I never knew girls like Violet and her friends in college, nor that such beings have ever existed. They feel wholly invented to me, thus there simply is no satire. Stillman is still a first class writer, so all the dialogue glistens with his typical craftsmanship and flair, yet it often feels devoid of meaning, coming off as quirkiness for its own sake. Which, while maybe a let down for Stillman fans, would still be fine if the comedy weren’t so all over the place too. The character who comes closest to feeling like true satire also best represents the unexpected (for me) disparity in Damsels‘ humor: the minor character of Thor (Billy Magnussen), a frat brother of Violet’s boyfriend Frank. Thor improbably never learned his colors as a child, he can’t verbally identify blue or green or anything. So Thor sets himself on the task of learning the names of the basic primary colors and their primary mixes, because he believes in the power of education. There is a funny idea here, but Thor, Frank and all the other fratboys are so cartoonishly stupid that it can be distracting at times, going far beyond satire into children’s movie level silliness. These characters, among other gags, left me confused what sort of film I was watching. This problem is compounded by the fact that there is little sense of movement in the story. Just when you think things are escalating, and that you’re figuring out what Stillman is trying to do, the film stalls or swerves to another place entirely. The film is episodic (equipped with cute chapter title cards), but lacks a connective drive.

But as I said in the beginning, the film has a way of keeping you glued in with its aggressive geniality. It has an adorable atmosphere, and doesn’t seem to be going for anything biting; possibly Stillman just wants to elicit a smile. Here I have to give the lion share of credit to the enchanting Greta Gerwig. Thank god the Arthur remake tanked, because I want to keep Gerwig right where she is as the indie It Girl of the moment. Gerwig makes Violet work. Violet is self-righteous, judgmental, and uniquely stupid, but Gerwig convinces you that Violet’s motives and heart are completely pure, that she truly does care, that she isn’t doing all this because she’s bitter or angry. Violet does honestly believe that creating a dance craze will change the world. Megalyn Echikunwoke is also quite good (even though her funniest character trait doesn’t appear until the end of the film), and her British accent makes her judgmental male-analyzing catchphrase – “He’s a playboy operator type.” – particularly funny. The Office‘s Zach Woods has a small but winning performance as the college’s pretentious newspaper editor who hates Violet. And though I wasn’t always sure exactly what Stillman was thinking with Violet’s moronic boyfriend Frank, Ryan Metcalf’s performance is so singularly specific that simply the sight of his face coming on screen often caused me to laugh out loud.

While I laughed at jokes like a campus building people keep trying to commit suicide off of, but is only tall enough to break people’s legs, I can’t say I saw where this was coming from or commenting on. Stillman’s track record means I will be revisiting this film in the future, to see if I can find new logic or nuance in it. But my first viewing left bewildered – if also slightly dazzled – by the bizarre cotton candy concoction the filmmaker whipped up. Maybe this one is on me. Maybe Stillman wasn’t trying to say anything, taking a huge departure from his previous style. Though I don’t really believe that. I would on the other hand like to believe that Damsels is just Stillman shaking that thirteen year old dust off his skills. But there is also the nagging feeling that Damsels‘ problems stem from Stillman not really being sure of what he was ultimately going for. And at times Damsels encroaches on Wes Anderson stylistics, as though Stillman were trying to leap-frog past his own style to catch up with his subgenre’s current state — something John Carpenter sadly also did with The Ward when he broke his own decade-long leave of absence. Maybe another problem is simply time itself. Stillman has written exclusively about people in their twenties, but it should be remembered that the man is 60-years-old now. College is a universal experience, and Seven Oaks is a fantasy world, so nothing about it feels out of touch exactly, but it completely lacks the astute world building of Metropolitan and Last Days of Disco. I frankly would like to see what Stillman has to say about life beyond our twenties. There is a big world past thirty.

On the grand scale of directors staying out of the game too long, Damsels is far closer to Avatar than The Ward. Fans of Stillman will want to see it, and will find things to like. You may not laugh as often as you’d like, but you will laugh. For those who aren’t familiar with Stillman, don’t start here. Start with Metropolitan.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars