“Why is this day different from all others?” is a question every Jewish family hears at the Passover seder. “Why is this biopic different from all others?” is a question that no one seems to hear in Hollywood. Factory Girl is the latest in a string of disposable and interchangeable biopics about people whose lives are destroyed by drugs and ambition, and it follows the same beats as every single movie of its ilk: young person becomes a star/genius, gets famous/brilliant, gets on drugs, dies (or, in some cases, recovers but their creativity bites it). Actually there is one thing that sets Factory Girl apart from other biopics: it’s about someone who was famous for no actual discernable reason.

“Why is this day different from all others?” is a question every Jewish family hears at the Passover seder. “Why is this biopic different from all others?” is a question that no one seems to hear in Hollywood. Factory Girl is the latest in a string of disposable and interchangeable biopics about people whose lives are destroyed by drugs and ambition, and it follows the same beats as every single movie of its ilk: young person becomes a star/genius, gets famous/brilliant, gets on drugs, dies (or, in some cases, recovers but their creativity bites it). Actually there is one thing that sets Factory Girl apart from other biopics: it’s about someone who was famous for no actual discernable reason.

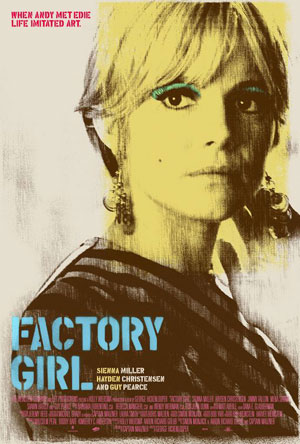

Sienna Miller plays Edie Sedgwick, a privileged rich girl who fell into the orbit of Andy Warhol’s Factory art scene in the 60s. The movie presents the two as fast friends, at least until Edie got involved with an unnamed “Musician” (unnamed and yet painfully obviously Bob Dylan), at which point Andy got jealous, they ‘broke up’ and Edie went off into drugs and eventually a death tastefully rendered in a textual postscript. What the movie never presents is a compelling understanding of why Edie became famous, or even what they fame meant. There are hints that some version of the film (which was famously recut and added to until the last possible moment) addressed these issues, issues which must lie at the core of any examination of Sedgwick. The movie briefly sets up a dichotomy between Warhol as the man who is all surface while “The Musician” is the man who is all depth – which would have been fascinating fleshed out into a movie about these two men. But this is a movie about Edie Sedgwick, who stands on the sidelines when these men finally clash in person. She’s a spectator in her own life story.

Actually, this movie sometimes feels like it wishes it was about Andy Warhol. Guy Pearce is fantastic as the bizarre and groundbreaking artist, finding the humanity that fueled his often-famous coldness. Pearce immerses himself fully into the character in a breathtaking way, and he controls every scene he’s in. Predictably, every scene he’s not in becomes a bummer, and as Edie and Andy drift apart the movie takes on a sense of doom not predicated on Edie’s eventual fate but rather the movie’s slow deflating. If there is anything that would make me able to recommend it, it would be Pearce’s fantastic performance.

But this isn’t the Andy Warhol story. It’s occasionally a platonic love affair between Andy and Edie, but it’s mostly about Edie, and sadly Sienna Miller can’t shoulder the weight. Her emotional scenes read like histrionics from Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, and as the movie goes on she starts to look more and more like Jerri Blank from Strangers With Candy. Miller doesn’t have the weight to hold the screen, and the fashions and hairstyles upstage her again and again. Which I wouldn’t have a problem with if I felt like the movie was doing it on purpose, commenting on the vapidity of Edie’s fame. But Factory Girl sets her up as a tragic figure, a sad cautionary tale about… well, I guess about the perils of being a vacuous bimbo.

As slight as Miller is, she never approaches the true depths of awfulness of Hayden Christensen, woefully miscast as the ersatz Bob Dylan. He looks like he was on his way to a costume party when he was wrangled to the set, and he delivers his lines in a bad imitation. But most of all Christensen has no presence. In the scene when “The Musician” and Warhol face off the deck is stacked – but in the wrong way. The scene plays out so that “The Musician” controls the situation with a quiet, angry charisma, but in reality Christensen is invisible, unseen in the powerful glare coming off Pearce’s performance.

Factory Girl should be seen as the end point for films about the 60s, at least until someone figures out a new way to do them. The bad wigs and the samey drug taking scenes and the casual mentions of Vietnam and the civil rights movement have been done to death already – although I do have to credit director George Hickenlooper with not using White Rabbit during any of the drug scenes. But that doesn’t make for a fresh take on the decade, which has come to feel less like a real era and more like a Hollywood pantomime. In a couple of years someone will figure out a way to shoot a drug scene that is new and interesting and would be era-appropriate, but in the meantime we need to close the door on the 1960s.

Biopics need to make compelling cases for their existence, and Factory Girl never does. It doesn’t offer insight into the 60s or The Factory or why Edie was famous or why we should care. It definitely doesn’t make a case for why anyone would want to put Jimmy Fallon in a movie, but it does make a good case for Guy Pearce being a remarkable and underrated actor. Beyond that, though, why should anyone sit through this rote and banal movie?