BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE

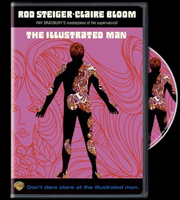

STUDIO: Warner Bros.

MSRP: $19.97 RATED: PG (w/ Steiger Ass)

RUNNING TIME: 103 minutes

SPECIAL FEATURES:

• Vintage Featurette: "Tattooed Steiger"

The Pitch

"It’s Creepshow meets The Outer Limits meets the paper I wrote for my English capstone course!"

The Humans

Rod Steiger, Claire Bloom, Robert Drivas

The Nutshell

Ray Bradbury’s collection of short stories called "The Illustrated Man" featured a clever, if slightly forced, method of tying the unrelated contents together. The conceit was that there was a man covered in tattoos and the author persona gazed at the tattoos, and they seemed to move, and tell those stories recounted in the book.

The Illustrated Man in film form features three of those short stories — "The Veldt," "The Long Rain," and "The Last Night of the World" — adapted to the screen and bookended by a frame story that remains largely unchanged from the print version.

"Oh yeah? Photograph this!"

The Lowdown

In the world of fiction, the short story is regarded as something of a artisan’s interest. The authors like them, because they’re compact and challenging; magazines like them because it’s something they can reasonably publish. Readers, however, don’t care for them as much, judging by the ratio of novels to story collections that tempt the American book-buyer. (Note: these data are circumstantial, and Chuck Palahniuk doesn’t count. For much of anything.) It’s an interesting format, though: catch an audience’s interest, spin their heads, then let them go.

It’s a format that transitions to a cinematic form with occasional success. Serials, such as The Twilight Zone, were essentially collections of short stories, related by their tone, but little else. Recently, TNT’s Nightmares and Dreamscapes and Showtime’s Masters of Horror have adapted shorts directly onto the small screen, with mixed results, using a similar tone (or, in the former case, a single author) to unite the different entries.

From now on, this is how I’m going to picture people who send me

angry e-mails about my reviews. Faint mustache and all.

In such a context, The Illustrated Man stands on its own. The filmmakers chose to try and tie the story adaptations together into a cohesive narrative, emulating the bridge story that Bradbury used in the published work. Rather than isolating each entry, such as is done with Creepshow, the stories here are intended each to contribute to the thrust of the frame story, which centers around a rage at the more unfortunate aspects of premonition. Rather than serving as a simple method for delivery (ala the Crypt Keeper,) this frame story becomes the main audience focus, with the story adaptations supporting it.

That frame involves an old transient (Steiger) who happens upon a young man (Drivas) hitchhiking across

Sure, Linus grew up. Everybody grows up. But he didn’t move on.

The young man sees a tattoo of a lion, and falls into Bradbury’s story "The Veldt," in which a pair of spoiled youngsters in a technology-centric future go out of their way to keep hold of their playthings, going so far as to murder their parents. Next, the young man is led into "The Long Rain," in which Bradbury imagined a Venus drenched in rain that fell so hard it could make you go deaf, and the four astronauts who try to find a glimpse of civilization (and salvation) in its misty wilderness. Finally comes the brief "The Last Night of the World," in which the few last humans on Earth predict a terrible catastrophe, and a man euthanizes his children (prematurely) to prevent them from feeling any pain.

At first glance, these stories don’t seem to have much in common. Taken on their own, as individuals or unlinked stories, they would be lesser creatures: decently-acted, but shallow. With the simple addition of the Illustrated Man’s vendetta against the woman who gave him his tattoos, though, they pull together with an extraordinarily narrow focus. The Illustrated Man’s anger stems from his hatred of being the bearer of prophecy. It’s an externalized and exaggerated mindset of many speculative fiction authors.

"Flies? Why would I care about flies?"

Speculative fiction is founded on extrapolation, into the past or into the future. Speculative fiction authors often take scenarios from today, boil them down into a couple of concepts, and plop them out of context in a different time so that they might better be examined, like specimens placed on slides. It would be a terrible thing were any of these authors correct in their predictions, since you’ll not find a lot of hopeful speculative fiction. That’s the Illustrated Man’s burden: he carries with him the loss of hope, and people see it and hate him for it.

The three stories step a layer further down and detail three abominations of the future, in the inhumanity among a technologically-distanced family, the necessity of isolation, and then the tricky and recursive "The Last Night of the World," in which predictive powers are questioned, and desperation is king.

Oh blessed veil, we praise you for withholding your secrets so cinematically.

We hope you never consider us worthy of the knowledge of that which you have seen,

excepting certain portions of Claire Bloom.

In a sense, The Illustrated Man is a well-formed dissection of what makes a speculative fiction author tick. That being said, it’s not a very engaging argument. Bradbury’s prose has always been faintly stilted, just that much too formal, and his dialogue is in a similar camp. He’s from a different literary generation, stylistically speaking, and that style fails to communicate well on screen. And, though Steiger does a terrific job emoting where necessary, the direction for his character too often leaves the audience unbalanced. Not on the edge of their seat, just kind of see-sawing

I’ve got more good things to say than bad about The Illustrated Man, though. It hasn’t aged well (better than Silent Running, fortunately,) but the engine the powers its script is still intact. I’ve got nothing but admiration for the filmmakers who managed to translate a sermon on fiction in three parts to the screen without sacrificing any of the punch of the message.

The Package

The only bonus included is a vintage featurette called "Tattooed Steiger" that goes into brief detail on the Guiness Record-holding make-up process of getting Steiger’s temporary tattoos ready for filming. Would you believe twenty hours?

"No, I would not."

Well, it’s true.

"You probably looked that up on IMDb."

Just shut the hell up.

7.7 out of 10