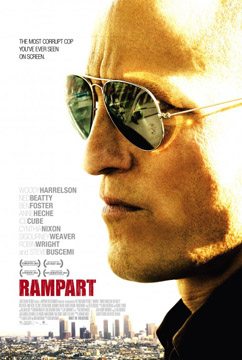

Rampart is the Shame of police movies. In fact, it crisscrosses last year’s critic’s darling on many levels as it takes its audiences through a crescendo of obsession and addiction centered around a raw and very personal lead performance. It’s one of those films where it’s hard not to get a little of the muck on you as a viewer. It’s so intimate and sometimes hard to watch because it uses that gift of movie escapism as a blunt instrument where we aren’t an audience as much as accomplices. That’s due in part to Woody Harrelson’s intense and bold performance as well as Oren Moverman’s meditative approach to storytelling. It’s a concussive little movie.

Rampart is the Shame of police movies. In fact, it crisscrosses last year’s critic’s darling on many levels as it takes its audiences through a crescendo of obsession and addiction centered around a raw and very personal lead performance. It’s one of those films where it’s hard not to get a little of the muck on you as a viewer. It’s so intimate and sometimes hard to watch because it uses that gift of movie escapism as a blunt instrument where we aren’t an audience as much as accomplices. That’s due in part to Woody Harrelson’s intense and bold performance as well as Oren Moverman’s meditative approach to storytelling. It’s a concussive little movie.

That said, this is not Bad Lieutenant. Not even close. Where that film was all about pushing buttons and showcasing the depths a man can plunge Rampart is a sun soaked look at a place in our recent history where the Los Angeles Police Department was in a state of extreme flux. Rather than choosing a side the film showcases the fine line between politics, hot button hype, and actual civic duty. Though Harrelson’s David Brown is the tip of the spear with his abusive and brutal ways, the suits (represented by the likes of Steve Buscemi, Sigourney Weaver, and Robert Wisdom) and their reactionary and media driven overcompensation are no less corrupt. Add to the mix the lawyers and people who operate in the gray areas (Robin Wright and Ned Beaty, respectively) and you have the sort of rogue’s gallery one would expect from a screenplay co-written by crime legend James Ellroy. On the surface it would seem a can’t miss proposition given the mix of talent (director/writer Moverman’s The Messenger was quite good and a huge boon to Harrelson’s recent dramatic surge) but there are factors which keep Rampart from being a classic, and just a solid rental a notch above the likes of Dark Blue and Harsh Times.

In 1999 on the heels of the Rodney King incident and fallout, the LAPD was undergoing incredible scrutiny. Police brutality was the topic of the day and the line between justice and punishment had become blurry. This fictional story introduces David Brown in the wake of that firestorm. A hard edged Vietnam vet cop with a very elaborate vocabulary due to a failed stab at becoming a lawyer, he’s a dangerous man by the sheer force of his ability to wriggle off the hook and defend his actions through obscure court decisions. Add to that his stubborn ways and volatile reaction to sex crimes (an Ellroy staple) and his extremely bizarre nuclear family and there’s enough of a powderkeg. When he’s accused of brutality after being caught on camera assaulting a perpetrator the gloves are off and a man who once walked the tightrope with finesse goes off the rails. Brown loses his grip and as he’s reaching for any ways to clear his name and keep his lifestyle going, Harrelson is given ample opportunity to shine both with an eerie calm about him as well as an explosiveness we’ve not seen in a while. This is not the same actor from Natural Born Killers. There’s a grace to his work now than only comes from decades in front of the lens. It helps to be able to personify a character who seems like a possible hero quickly becomes anything but, one which actually takes a journey over the course of the film rather than follow a series of narrative dots to a destination. It has a lot more in common with a freestyle character study than a crime flick.

A lot of that is due to Moverman and Ellroy’s decision to focus a considerable amount of screen time to Brown’s odd lot of a family. Two daughters from two different mothers with a little incest as the backdrop, a pair of lesbians with a sexual connection to Brown, all of whom with some serious issues with him. There’s a very interesting and emotionally raw tone to this aspect of the film and though people expecting gunplay and grandstanding will tune out, it’s what elevates the whole.

Violence, sex, animosity, and prescription drugs all fuel David Brown and it’s in this cocktail of components where the parallel to Shame really surfaces. In many ways Harrelson is Michael Fassbender’s equal in the honesty and lack of artifice in their portrayals. Harrelson has that coyote twinkle in his eye still, though. Something that’s served him so well over the years as he jumps from comedy to drama effortlessly. It helps cut some of the harsher edges to his character. It’s hard to hate David Brown, and that’s due a lot in part to Woody. His charm shines through damn near anything. It also helps that David Brown’s in many ways the kind of protector we want, one fueled totally by putting an end to bad people and willing to sacrifice their very soul to achieve it. Ellroy’s pen shows up the most in some very nice dialogue and interplay that doesn’t ascend to the heights of his literary works but delivers much-needed vitality to a very tired genre. Moverman’s camera never shows off but also doesn’t stick to the rulebook and it helps the central performance be the star of the film.

It’s a good movie. The supporting cast is excellent and seeing Ned Beatty onscreen again is a delight. It also helps that the awful overacting of Jon Bernthal is limited to one scene. Ben Foster, who appeared very effectively with Harrelson in The Messenger is on board as a producer and as a crippled homeless person. He’s fine in the role but Foster’s an actor not unlike Jeremy Davies who seem to cherish overcooking their performances and choosing quirky parts in chunks rather than diversifying more. It’s a bit showy but he’s talented enough to sell it.

Recommended, but don’t expect either Prince of the City, Training Day, or Bad Lieutenant. This isn’t a corrupt cop cornerstone, just a nice brick in the foundation.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars