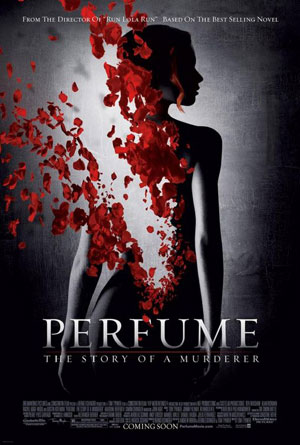

Smell is, unless you’re John Waters and in possession of a few hundred Odorama cards, the toughest thing to get across in cinema. Most films rely on Pavolovian reactions to visuals to indicate the ideas of smells, but rarely try to actually get odor across. Run Lola Run director Tom Tykwer, in his adaptation of the best selling novel Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, tries to do just that, and the whole film hinges on whether or not he succeeds. You see, his protagonist, Grenouille, approaches the world almost exclusively with his nigh upon supernatural sense of smell.

Smell is, unless you’re John Waters and in possession of a few hundred Odorama cards, the toughest thing to get across in cinema. Most films rely on Pavolovian reactions to visuals to indicate the ideas of smells, but rarely try to actually get odor across. Run Lola Run director Tom Tykwer, in his adaptation of the best selling novel Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, tries to do just that, and the whole film hinges on whether or not he succeeds. You see, his protagonist, Grenouille, approaches the world almost exclusively with his nigh upon supernatural sense of smell.

Tykwer pulls it off, for the most part. He creates audio-visual combinations that actually evoke smells, instead of just invoking them. It’s a tricky business, and occasionally Tykwer’s efforts get in the way of his own work, but when everything comes together right – such as in the middle of the filthy fishmarket where Grenouille is born and unceremoniously left to die – it’s close to amazing. More amazing is how Tykwer integrates this selling of the smell into the movie until you get to a point where it’s barely noticeable anymore; it’s become part of the storytelling process.

Unfortunately, many other elements of Perfume are a ragged mess, including the story itself. Grenouille, born in Paris in the 18th century, and gifted with the most finely tuned sense of smell ever seen, is taken to a grotesque orphanage and then to a meat rendering plant. He’s damned to spend his days among the most foul stenches, although he doesn’t recognize them as foul, as he’s never smelled anything nice. One day he travels into the heart of Paris and discovers a world of olfactory amazement – especially the smell of a beautiful young redhead. Not knowing how to interact with the girl, Grenouille accidentally kills her. He notices that her wonderful scent soon fades, and he decides to learn how to forever preserve a smell. His quest takes him first to an Italian perfumer in Paris, who teaches him the basic art of scents, and then finally to a rural retreat where he learns the more esoteric aspects. As he learns more he kills more women, capturing their scents with the goal of making the world’s most beautiful perfume.

Tykwer’s version of Patrick Suskind’s novel staggers forward in the first half, often without any obvious momentum. Grenouille is a strange, solitary and often unlikable character (least of all because he kills), and as stumps around the back alleys of Paris, always sniffing, he can be trying company. The film seems to be picking up when Dustin Hoffman is introduced as Baldini, the perfumer, but then everything threatens to fall to pieces. There are thrilling scenes, like the one where the utter novice Grenouille demonstrates his astonishing nose to the unbelieving old man, but Hoffman is playing his role to tilted towards high camp that he’s ludicrous. Hoffman is so hammy that the film could never hope to be kosher.

Thankfully the Hoffman interlude is a relatively short one, and the film moves on into the by far stronger second half. Imbued with a purpose and basic social skills, Grenouille becomes an easier character to like, even if he does ever more terrible things. His killing is a compelling metaphor for the process of all artistic creation – you must capture and subdue emotions and memories to turn them into great art. And the art that Grenouille pursues is great, almost unfathomably so. Fans of the book will be happy to know that the ending exists intact; newcomers should be warned that the final twenty minutes become heightened and fantastical, but perfectly so. The story dares to go big and strange places, and you have to love the movie for not shying away from that course, which will certainly be far too odd for some viewers. I relished every moment of it.

Relative newcomer Ben Whishaw plays Grenouille with a grimy rat-like intensity. I don’t think any screen actor who was not starring in a Bret Easton Ellis adaptation has ever been asked to sniff so much in a film, but Whishaw often finds ways of making the sniffing reflect what Grenouille is thinking or feeling. I found myself wondering if his throat and nostrils got very dry from doing that much sniffing.

Balancing the manic scenery chomping of Hoffman in the first half is a fairly glorious Alan Rickman in the second half. A local noble in the town where Grenouille is finding his victims, Rickman plays a pre-French Revolution forensics detective. He wants to get into the killer’s head! Think CSI: Versailles. Only Rickman could pull off such an anachronism so very well. He is ably assisted by the impossibly luscious Rachel Hurd-Wood as his daughter, and the ultimate prey for Grenouille. I interviewed Hurd-Wood earlier this year and the lewd thoughts I had while watching this film would occasionally collide with my memories of the very young seeming girl and I would feel awful.

It’s hard not to have lewd thoughts while watching Perfume, though. Tykwer understands how sensual smell is, and he also really understands the sexuality of earthy redheads in bust-baring period costumes. To say that Perfume is heavy on nudity would be understating the case exponentially – let’s just say that this film will become a treasured DVD in the collection of many adolescents. It’s strange, though – the nudity and sexuality in Perfume does inspire naughty thoughts, but not the dirty kind that an American film with the same full frontal exhibition would. There’s something deeply different in how Europeans approach nudity – maybe it comes from the actresses not carrying the kind of shame about it that American actresses often do.

What surprised me most about Perfume was how entertaining it was. While the pace could lag at times and while the story felt frayed around the edges, the movie never even hinted at falling into the kind of period piece morass I feared. In many ways Perfume is Silence of the Lambs meets Les Miserables, with everything that entails.