Children of Men is about a miracle. Children of Men is, itself, a miracle. It’s a movie that can single-handedly remove the scales of cynicism from your eyes, reminding you of what wonders cinema is capable. It’s a movie that rejects the two modern directions of the screen – a shrinking to TV size for the eventual DVD afterlife and a bloating of effects in an attempt to subdue us with manufactured wonder. Children of Men is defiantly cinematic, and it uses cutting edge technology and effects not as ends to themselves but as ways to tell the story and engage us in a complete – and completely realistic – world.

Children of Men is about a miracle. Children of Men is, itself, a miracle. It’s a movie that can single-handedly remove the scales of cynicism from your eyes, reminding you of what wonders cinema is capable. It’s a movie that rejects the two modern directions of the screen – a shrinking to TV size for the eventual DVD afterlife and a bloating of effects in an attempt to subdue us with manufactured wonder. Children of Men is defiantly cinematic, and it uses cutting edge technology and effects not as ends to themselves but as ways to tell the story and engage us in a complete – and completely realistic – world.

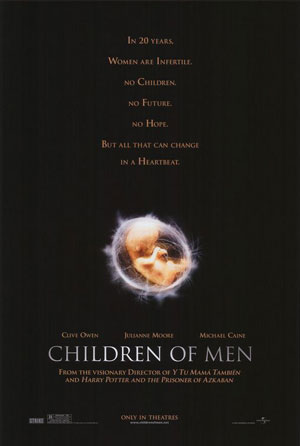

The film is set in the year 2027, 18 years after the last human being was born. No one knows why all the women on Earth have become infertile, but at this point it’s becoming moot; humanity is on an express train to extinction. The infertility, and other escalating crises that are all too familiar to audiences in 2006, have left most of the world a chaotic hellhole. Only Britain carries on with any semblance of order and civilization. This, of course, makes it a mecca for foreigners looking for a decent life, but draconian laws keep them out; when they do get in illegally, they are rounded up, caged and shipped off to all-too credible “’fugee” camps. Meanwhile, some people rage against the dying of the light and the tightening of the government’s grip – there’s a mythical Human Project out there somewhere, working on a fix for the infertility problem. And closer to home and more tangible are the underground terrorists in the Fishes, a group dedicated to immigrant’s rights.

Clive Owen is Theo, a man who was once an activist, but who has been beaten down the hopelessness of the world around him. He shuffles through life as an office drone, drinking and getting stoned with his friend Jasper, an old hippie type who grew up in the 80s and 90s and listens to gangsta rap. One day Theo is kidnapped by the Fishes – it turns out that his ex-wife (Julianne Moore) is one of their leaders, and she wants his help. The group has found a girl – a ‘fugee, no less – who is pregnant. She wants to get the girl to the Human Project, but Theo is the only person she can trust.

Director Alfonso Cuaron’s world of 2027 is fully realized. He doesn’t take us on a sight-seeing tour of future Britain, but he packs his frame with detail and activity. Engaged viewers will find that the world isn’t sketched but presented in total, captured the way a cinematographer in 2027 would capture it, and the details that Cuaron stuffs in reward multiple viewings. It’s exhilarating in the way I don’t think a cinematic future has been since Blade Runner, but is much more realistic than that one. We’ve been living in the future for the last decade, and I think we have all come to realize it looks just like the past, but with different clothes.

The director’s vision feels so right, and also so current. The best science fiction takes fantastical ideas and uses them to comment on who we are today, and Children of Men is no exception. In the opening scene the world’s youngest person, Baby Diego, is beaten to death at age 18; in a detail that rings completely true, the people of London engage in the kind of mass-mourning in public that has become so common since the death of Princess Diana. In another scene, Theo visits a rich cousin who is holed up in a fortified home that was once a power station, where he keeps works of great art. Michelangelo’s David, damaged by rampaging Italians, sits alone and unappreciated, surrounded by guard dogs. In the dining room hangs Picasso’s Guernica, a commentary on the misery these people live with every day, but also a great work sequestered away from the prying eyes of the proles and the poor and the ‘fugees. And Cuaron has a sense of visual humor in moments like this, where he’s decrying the way art is hoarded – floating outside the window of this power station is a giant inflatable pig, recreating the album cover of Pink Floyd’s Animals. And maybe more than slightly commenting on those living within.

If Children of Men had just been a thrilling and wonderfully constructed science fiction parable, it would still be one of the best movies of the year. But there’s something more to the film that lifts it to the level of masterpiece – Cuaron and his genius cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki shoot a number of complicated sequences in what appears to be long, unbroken takes. The reality is that there must be digital trickery in there somewhere, stitching together shots, but these moments are presented subtly, without fanfare. On a second viewing you may have the ability to sit and think about the shots critically, but the first time around you find yourself thinking, ‘Wait a second, there hasn’t been a cut in a really long time.’ These shots never announced themselves, they just happen, and they happen at the right time, when they can add to the drama of a situation. They’re thrilling, and when was the last time you went to the movies and were thrilled by something technical that wasn’t a mess of pixels?

Clive Owen anchors the film – his Theo is in pretty much every single scene, and his journey from disenfranchised apathetic guy to someone willing to put his life on the line for the smallest shred of hope is an inspiring one that plays out slowly and naturally. Often the moments of realization and change happen to Theo in the long shots, which makes them all the more incredible. Owen is the only person who could have played this role, bringing with him both a sense of tired heroism and lived-in realness; he’s a walking paradox in that there’s nothing of Hollywood in him and yet he feels like the ultimate synthesis of the great movie men of the 40s and 50s.

He’s surrounded by fantastic actors who are all professional enough to know the line between stealing the film and making their mark. Michael Caine, one of the most hit and miss actors of our time, comes closest to stealing the whole thing as Jasper, the soft, liberal heart of the movie. Funny and sort of wise, Jasper is the sign from the start that there’s still something good left in Theo – otherwise this old man who sells weed to the local stormtroopers wouldn’t bother with him. Julianne Moore’s role is briefer but the closest thing that the movie has to source of exposition; she does fantastic work making us feel the old, lost bond between her character and Theo. And Chiwetel Ejiofor is tremendous, finding the exact spot where the best intended liberal bleeding heart steps over the line into something darker and more dangerous.

Many people only see the bleakness of Children of Men, but that’s unfair. The film is the most hopeful of the entire year, even moreso than the saccharine totality of all the year’s inspirational sports films jammed together. The whole movie is about the tenacity of hope, and the way that a small flicker of it can reignite even the most seemingly spent soul. There’s a scene at the end of the film that shows this in the most purely visual terms (which I won’t ruin for you) that contained such grace, meaning and beauty that I was on the verge of tears. Children of Men posits a future that is as fucked up as possible and then says that there’s still a chance, there’s always a chance, that things could get better. And even more than that it says that any of us can take that hope and run with it – the possibility is there, presenting itself to us, if we only take the opportunity. That’s a great message for a world that is feeling more than a little battered, looking at problems that the experts tell us have solutions only decades in the future. If they can even be solved at all. Children of Men tells us that they can be solved, after all. Life – and humanity – will always find a way.