We Are Marshall is the most insidious kind of bad movie – the very well made kind. It’s an easy, often beautiful, movie to watch, and if you’re not inoculated against the most base brand of movie cheese, it’s an easy movie to weep over. But it’s still bad, bad at it’s very core, because it just doesn’t trust its own story.

We Are Marshall is the most insidious kind of bad movie – the very well made kind. It’s an easy, often beautiful, movie to watch, and if you’re not inoculated against the most base brand of movie cheese, it’s an easy movie to weep over. But it’s still bad, bad at it’s very core, because it just doesn’t trust its own story.

Here’s the set up for the film, in the least flowery terms I can use: After an away game, the Marshall University Thundering Herd football team, the coaching staff and some prominent fans, who also happen to be prominent members of the Huntington, West Virginia off-campus community, die in a plane crash. Among the 75 dead: the son of a local industrialist, who leaves behind his cheerleader girlfriend, who just recently became his fiancée. Also killed is a local family man who took the seat of assistant coach Red Dawson at the last minute. After the crash, the Marshall University president and trustees don’t know what to do – whether to scrap the football program or restart it. Thanks to the perseverance of the surviving team members and an eccentric coach from another state, the Marshall team is rebuilt.

I think the emotions are obvious – this is a tale fraught with inherently weepy moments. And these moments just happen to often be true. Yet McG, the director of We Are Marshall, never trusts the real story and instead heaps on strings and dramatic camera movements and instructs his actors to keep their lower lip trembling, to always be on the verge of tears. He slathers it on, scene after scene, drowning the true impact of the story with fake indicators of meaning and depth. This is exactly the kind of movie Paul Greengrass was reacting to when he made United 93 in as verite a style as he could.

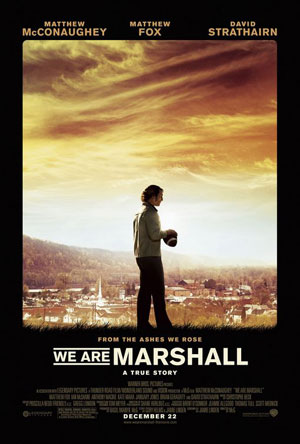

What makes this sentimental claptrap hurt all the more is that McG has filled his movie with strong actors. Matthew Fox is Red Dawson, and the actor seems to have been born to play a guy who is always on the verge of tears, as Fox seems to always be on the verge of tears (this is also true, distressingly, in real life). He’s second billed, but this is really his film, and general teary-eyed quivering aside, Fox does an admirable job. David Strathairn as the reticent University president retains his dignity through much of the film until the script reduces him to a brainiac coming under the tutelage of mighty jock Matthew McConaughey. And Ian McShane takes a one-note role – that industrialist whose son died and who is very against the team starting back up – and injects real humanity into it. You can feel the hackneyed script buckling beneath him.

But all of this is undermined by Matthew McConaughey’s ludicrously cartoonish performance as the new coach. Talking out of one side of his mouth like a stroke victim, dressed like a 1970s weatherman and occasionally remembering to walk like he has a load of shit in pants, McConaughey is laughable in most of his scenes. Watching him interact with Matthew Fox more than once brought to mind scenes between Roger Rabbit and Bob Hoskins. The film, with it’s constantly grim storyline, needed a slightly wacky performance here, but McConaughey is zany, sort of like Gallagher, but with worse hair and no watermelons.

We Are Marshall is sort of a football film – it’s centered around a football team, anyway. Sadly, for all of his technical skill, McG never figures out how to stage a football game in an interesting way. To be fair to him, I don’t think many people have – football in most films is boiled down to a montage of bone-crunching, emergency room-baiting tackles and heroic long throws. We Are Marshall never significantly strays from that formula.

How will you be able to know if I am right and We Are Marshall is as insidiously bad as I say? Here’s a test: when a friend sees the film, ask their opinion. If it’s something along the lines of “It wasn’t that bad,” you know that not only is the film bad, it’s succeeded. This is the kind of film that works to trick an audience that being “good” isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be. We Are Marshall may also convince moviegoers that the problem with it isn’t that it’s a sappy piece of manhandled Hallmark sentiment, it’s that the people who don’t like it just don’t have a heart. It’s the film that doesn’t have a heart though, as it takes the true tragedy – and true uplift – of the Marshall University story and turns it into a cynical grab for maximum tissue usage.