Adventure Time #1 (Kaboom, $3.99)

by Graig Kent and Adam Prosser

Graig: I’ve been a fan of Cartoon Network’s Adult Swim block since, well, since before it was its own lineup. I came to know Space Ghost: Coast to Coast in 1995 and it was instrumental in acclimatizing my comedic taste buds to the more esoteric and absurd. When Space Ghost sprouted into offshoot programs at the turn of the millennium like the Brak Show, Aqua Teen Hunger Force, and Sealab 2021, I couldn’t get enough, literally, since we don’t have Cartoon Network in Canada, and bootlegs on-line weren’t as readily available as they are today. In the intervening years, Cartoon Network, and Adult Swim in particular, were responsible for redefining what both comedy and animation can be, and continue to do so. I know Adventure Time isn’t part of the Adult Swim block, but instead is a new-ish (debuting in 2010) and key component of the Cartoon Network’s all-ages line-up, and that’s about the extent of my knowledge on the show.

I’ve heard rumblings recently on message boards and internet whatnots of this deliciously bizarre kids show that makes Spongebob look as buttoned-down as King of the Hill, but, again without the benefit of Cartoon Network and a lack of promotion of its airing on the Canadian broadcaster Teletoon (currently at a convenient Sunday, 1:30 PM according to the website) it’s kind of slipped past me. Adam, how did you come across the show?

Adam: The show first got started as a YouTube clip, which was the de facto pilot. Some friends showed it to me, and I have to admit, I had absolutely no idea what to make of it. If it hadn’t obviously featured the voice of Futurama‘s John DiMaggio as Jake the Dog, I would have thought it was some kind of experimental film from the 70s, or something produced by asylum inmates as a form of therapy. Or maybe a bizarre sixth grade final project made by unusually talented students. The show is weird, is what I’m saying. Set in the (apparently post-apocalyptic) Land of Ooo, the show does its best to seem like a visualization of a game of make-believe played by imaginative, and possibly mentally disturbed, children. The two heroes, Jake the Dog (who has magical stretching and size-changing powers) and Finn the Human (monster slayer, and seemingly the last of his species) spend as much time hanging out in their SUPER-AWESOME TREE FORT or getting into discussions and arguments about stupid stuff as they do actually going on adventures.

Graig: So, unlike you, I come to this comic with next to no understanding of what the show is, its storytelling structure, its characters, it’s style, its sense of humour, and I have to admit, I was completely taken for a ride. I don’t understand a lot of it (and I hazard a guess that being a fan of the show will only clarify so much), but from page two — a full page spread introducing the cast and the setting via a manic series of arrows and info balloons filled with slyly funny wordplay reminiscent of Scott Pilgrim‘s descriptors — I was on board with what it was and where it was going. Throughout, there’s a sense of complete liberty — or rather a lack of defined rules — that the storytelling could go anywhere. And it does (I love “Jake suit” too, dude). There’s also the fleeting intrusion of self-awareness that lends the book much of its comedy, as well as the carefree attitude of the characters who seem to have no sense that anything they’re a part of can go wrong.

Adam: That’s very much in line with the show. It seems like it’s trying to capture the mindset of a child as thoroughly as possible, but with a level of honesty and self-awareness that makes it funny for adults. There aren’t “jokes” per se, just stuff that’s hilarious in its randomness, stuff that you can imagine a kid throwing out there without thinking it was meant to be funny. And it’s also got a lot of the same feeling that you get with the more bizarre webcomics–right down to the alt-text like asides at the bottom of some of the pages–which is why Dinosaur Comics‘ Ryan North was such an inspired choice as a writer.

Actually, the comic was obviously geared very strongly towards evoking the rhythms of the TV show, which is what made it funny for me. I could literally hear the characters’ voices in my head as I read it. I can’t imagine how it would come off to someone who hadn’t seen the show, but apparently it worked for you, so, great. But for fans of the show, rest assured, this is exactly what you would want out of an Adventure Time comic. The only misstep, I think, was the “to be continued” ending–the show regularly manages to deliver greatness in ten-minute chunks, so there’s no reason a comic story needs to expand beyond 22 pages.

Graig: Artistically speaking, this reminds me of James Kolchaka a whole bunch, visually and in tone, though scaled back in its innocence, mercifully. I agree that Ryan North’s frequently hilarious on-line comic strip, Dinosaur Comics, has made him well primed for this gig. The illustrations by Shelli Paroline and Braden Lamb are exceptionally clean and wildly amusing, which I’m assuming is an on-model style to the cartoon, but Adam, you could judge better.

Adam: …It is. The cartoon basically looks like an indie comic anyway.

Graig: Meanwhile there’s a back-up feature (which seems to be something that will be present each issue) from an indie comics creator that’s more in their own style featuring characters from the show. Here it’s Spiral Bound creator Aaron Renier. Not that I think the book needs it,as North’s serialized opening story is definitely entertaining enough to validate the admission price, but the back-up, especially in exposing lesser-known creators to a broader audience, is a definite gift. Renier’s story is goofy but adorable in its own slightly demented way. This is definitely a comic for the weird kid in your life (and if that weird kid is you, that’s okay).

Adam: I’m always in favour of licensed spinoff comics when they’re done well, because I think they’re the most logical way to draw new readers into comics, and this is almost a perfect storm. You’ve got a property that jumps perfectly from one medium to another, appeals to kids and adults, and brings a very indie sensibility to the mainstream. Recurring kudos to BOOM! which has really shown itself to be a serious, professional company that wants to expand the scope of the comics medium. In an age when many of the smaller publishers are going with stuff that’s almost as esoteric as the average superhero comic, or pandering with T & A, it’s nice to see one that thinks laterally.

Graig: I agree fully. Honestly though, as much as I enjoyed everything in this issue, my favourite part of this book: the Creator Bio/Next Issue page. I don’t know what it is about this page that tickles me so pinkly, but the photo of Lucy Knisley under “Also featuring: ‘Laudromarceline'” has doubly sold me on the next issue. It’s now a priority to start watching this show, Actually at this stage I’m hoping it lives up to the comic.

Adam: Oh it does.

Graig: Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Adam: Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

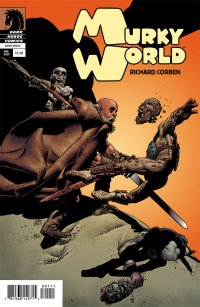

Murky World One Shot (Dark Horse, $3.50)

Murky World One Shot (Dark Horse, $3.50)

By D.S. Randlett

Sometimes the story’s beside the point. That’s not to say that the story in Richard Corben’s Murky World is nonexistent, it’s just not particularly novel or gripping on its own merits. Rather the story of Murky World exists as the framework for Corben’s signature blend of world building and great artwork, something for his master’s skill to elevate beyond it’s mere existence as a series of plot events.

This issue literally moves like a dream, with the bearded protagonist making his way through a series of disparate challenges in a desolate fantasy world. Corben’s art makes the dust that linger in these pages come alive, and the events that transpire unfold as if in a lucid nightmare. Things make sense, but only in inarticulable dream logic.

The art is very much the point of this book. Corben is an artist who can imbue everyone of his characters with a sort of weary sentimentality. No matter how weird or dark his worlds and characters, he can always evoke a sense of connection and empathy, a sense of life. He is a visual storyteller almost without par, the only touchstones for the sense of tone and flow that he evokes here being Bergman and Kurosawa, and he doesn’t disappoint with Murky World. He tells stories not so much with words and action, but through faces.

As such, I would not hesitate to recommend Murky World. But, I can definitely see how one’s mileage could vary from mine here. Corben eschews more comfortable modes of storytelling, and this may distance some readers, but it is still very much worth finding a way in.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

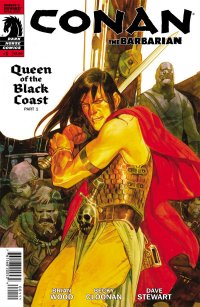

Conan the Barbarian #1 (Dark Horse Comics, $3.50)

By Bart Bishop

“What is best in life?” That phrase and what follows it has permeated popular culture for the last thirty years. Conan the Barbarian, however, has endured for even longer. Created by Robert E. Howard in 1932, the character has a long tradition in print. His prose stories originally appeared in the pages of Weird Tales, the famous pulp magazine, and later in Marvel Comics. The latter introduced a relatively lore-faithful version of Conan the Barbarian in 1970, written by Roy Thomas and illustrated by Barry Windsor-Smith. Smith was succeeded by penciller John Buscema, while Thomas continued to write for many years. In 1974, Conan the Barbarian series spawned a mainstream first, the more adult-oriented, black-and-white comics magazine Savage Sword of Conan, written by Thomas with art mostly by Buscema, which did not have the Comics Code stamp. In short, the character has quite a pedigree.

Conan, unfortunately, lay quietly in hibernation for years until Dark Horse Comics began their comic adaptation of the saga in 2003. Entitled simply Conan, the series was first written by Kurt Busiek and pencilled beautifully by Cary Nord. This series went back to the well of Howard’s stories, having no connection whatsoever to the earlier Marvel comics or any Conan story not written or envisioned by Howard. They released a second series, Conan the Cimmerian in 2008, and a third series (Conan Road of Kings) began in December 2010. Now, this new series is a ‘sweeping adaptation of Robert E. Howard’s fan-favorite “Queen of the Black Coast,”‘ in which, according to solicitations, ‘Conan turns his back on the civilized world and takes to the high seas alongside the pirate queen Bêlit, setting the stage for an epic of romance, terror, and swashbuckling. This is Conan as you’ve never seen him, with the combination of one of Robert E. Howard’s greatest tales and the most dynamic creative team in comics!’

That dynamic creative team is Brian Wood and Becky Cloonan, two individuals that would not be my first choice to write a fantasy tale of high adventure. I’ve been a fan of the writer for a long time, having picked up his Channel Zero a decade ago and followed his counter-cultural work ever since. He signed an issue of DMZ for me at a convention, and when I think of the writer I envision politically charged, contemporarily relevant stories. Cloonan, for instance, collaborated with Wood on Demo, a mini-series that put a unique spin on burgeoning super powers. Although I loved that series, and love both of these people, I never envisioned them handling something like Conan. Bear in mind I’ve never read Northlanders, the writer’s historical fiction series set during the Viking age, so I didn’t know what to expect when opening this comic.

Advertised as “the most-requested Conan adaptation”, this definitely feels like a fresh take on the character. I’ve read several of the books, all of Marvel’s stuff, and a good chunk of Busiek’s Dark Horse interpretation, so I’d consider myself a fan of the character. Not an ardent fan, but passionate enough to be concerned about respect being warranted to the character. Conan’s philosophy and lifestyle is an appealing one: he’s a nomad that carries only what he needs, can live off the land, knows how to have a good time, distrusts authority, is slightly superstitious and yet has an optimistic hope in human nature. What sets Conan apart is that although he’s uncivilized, he is not an idiot: his quick wit leads to, at this point in his life and beyond, a worldly wisdom and weariness that is to be admired.

I’ll say this is the most heterodox I’ve ever seen the character. I suspect what attracted Wood to the pulp hero is his, Conan’s, distrust of authority; there’s a bit of punk rock in Conan. When he’s introduced in “Queen of the Black Coast Part I”, he’s riding for his life from pursuing soldiers, and loving it. Escaping by the skin of his teeth, Conan stows aboard a trading ship and explains his story to the captain, Tito. They become fast friends, and Tito then explains the backstory of Bêlit, a pirate queen of substantial power and mystique. Conan, realizing he has complicated his new friend’s life, vows to find Bêlit and put the fear of Crom in her. This leads to a truly bizarre experience on the open water, when Conan and Tito encounter a seemingly abandoned ship…

In summary that sounds like an effective first issue, but Wood stumbles in the execution. He has Conan’s voice down pat, portraying the hot headed youth as quick to temper, hard headed, and wary of big city ways, but also charismatic and loyal. Wood also avoids what I like to call the “thees and thous”, affected dialogue that fantasy writers rely on to give the precedings a sense of antiquity and tramontane (Thor is often a victim of this contrivance). Unfortunately, this issue suffers from telling and not showing, slowing to a hault as Conan spends multiple pages explaining why he was being pursued by soldiers. Why not start the story off at the bar from the night before? The fractured narrative feels anachronistic, a modern addition that strays too far from Howard’s intentions. After all, Howard’s original “Queen of the Black Coast” started with Conan having sailed with Bêlit for years, so this issue (and presumably the majority of the series) is entirely a product of Wood’s mind. The background on the pirate queen is handled more gracefully, but the last few pages are convaluted and impossible to follow.

The last eight pages are almost entirely silent, giving Cloonan a chance to shine. Although I was hesitant of her taking over for this title initially, she has swayed me in her favor. Her rendition of Conan is particularly striking; much leaner than usual and with a roguish approachability fitting of a pirate. His eyes are also perfectly dangerous. Bêlit, as well, is unnervingly otherworldly and yet still believably intoxciating. It’s those last few pages, however, that are bothersome: first Conan leaps overboard and swims to the ghost ship, then appears to halluciniate being dragged underwater by Bêlit, only to awake in a fog on an empty ship (Bêlit’s? Tito’s?), but then is revealed to have been on Tito’s ship all along? I understand that Wood is relying on Cloonan hear to jar the audience and build atmosphere and dread around a woman that is described in the solicitations as Conan’s “match”, but a third of the book is an unnecessary amount of time for what amounts to very little. The cover, however, is a striking image that manages to summarize the content and theme of the book by putting Conan in a classic pose without resorting to Frank Frazetta homaging.

A fresh jumping on point for new readers and fans alike, but it manages to suffer from too much information and too little at the same time. It’s an exciting experiment, however, handing the reigns over to Wood and Cloonan and I’m anticipating where it goes from here.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Batman: The Brave And The Bold #16 (DC Comics, $2.99)

Batman: The Brave And The Bold #16 (DC Comics, $2.99)

By Devon Sanders

I may have just read the best Batman comic I’ll read all year.

On second thought…

I may have just read the best comic I’ll read all year… just in time to see it cancelled.

I’ve made no secret of my love for Warner Bros.’ superhero cartoon universes. From The Superman Adventures to The Batman Adventures to Justice League Unlimited and more, there is a simple truth of what makes comics great. The cartoons have this wonderful understanding that everything that came before, in comics, should have a place at the creative table. Everything is up-for-grabs. Nothing is deemed illegitimate.

A lesson the actual comics they draw from just can’t seem to grasp.

And that’s what makes the cancellation of Batman: The Brave And The Bold with its 16th issue, especially sad. This comic has displayed nothing but brilliance. While DC’s been bending over backwards to jettison their history and jury rig it with one shared vision, this comic, inspired by a cartoon that is informed by comics, has consistently been the most visionary book on the stands and yet largely ignored because it doesn’t adhere to the currently established continuity. Therefore, it’s deemed a comic for kids.

So wrong.

Batman: The Brave And The Bold #16 is a celebration of all things, Batman and more importantly, comics. When Batman graciously offers to display some of his many specialized Bat-Uniforms during Gotham’s Fashion Week festivities (New York’s Fashion Week coincides with this book’s release date. Brilliant!), Teen Titan’s villain, The Mad Mod simply must have them for his collection. The plan is foiled by Bat-Mite with help from Batgirl and a Valentine’s tale referencing past Batman comics adventures, romance comics, a trio of supervillain musicians, Charlie Brown strips and those incredible 1950’s Lois Lane covers ensues and all within the domain of 20 pages!

Writer Sholly Fisch crafts a tale that will appeal to fans of fun, crafting a comic full of in-jokes while managing to make it all accessible to anyone who simply enjoys reading a well-crafted story. Fisch displays a true comedian’s timing in his writing, not an easy thing to capture in print, while delivering simply solid storytelling. Fisch really needs to be called up to DC’s or any publisher’s “bigger” titles. Now.

Artist Rick Burchett pulls this all together with his simple, understated style. Burchett’s art flows easily from flat-out action to cover homages while paying close attention to the needs of the writing. Burchett, in my opinion, is one of comics’ best draftsmen and always worthy of whatever praise is heaped upon him.

Batman: The Brave And The Bold #16 is unfortunately, a final issue and yet, isn’t. It is a simple statement of what makes comics a great medium in which to work. We need more comics like this.

Now.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

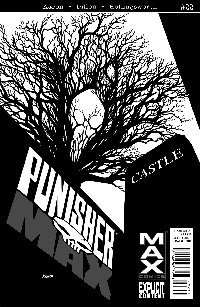

Punisher MAX #22 (Marvel, $3.99)

By Jeb D.

Marvel’s managed to get quite a bit of mileage out of The Punisher (among other things, so far he’s had as many movies as Spider-Man or the Fantastic Four), particularly when you consider that he appeared, at first, to be simply a small bright spot in a forgettable parade of 70’s Spider-Man baddies. Writers from Steven Grant to Rick Remender have found surprising ways to keep the concept fresh, but of course it’s Garth Ennis who goes down as the Punisher writer of record for posterity: he’s handled him in the regular Marvel U (more or less), but his run on the character under the MAX banner represented a fascinating opening-up of possibilities and widened scope, addressing a world of crime and corruption beyond the familiar urban mean streets, and introducing a strong (if often short-lived) supporting cast (the genially monstrous Barracuda even got his own spin-off miniseries). When Ennis left the book, his valedictory story, Valley Forge, Valley Forge, would have been a fitting end to the saga. The idea of continuing the book seemed commercially questionable (I’d be very surprised if even a relatively strong-selling MAX title really pays for itself). Crime writers like Gregg Hurwitz and Victor Gischler pulled off some nicely self-contained stories, but momentum had been lost, and the series concluded with a giant-sized finale. Enter Jason Aaron, who took it upon himself to write the final chapter of the MAX version (restarted with a new #1) of Frank Castle. And speaking in general, I’d say he bloody well succeeded (if you get my drift).

Aaron’s approach was in some ways the opposite of Ennis’: yes, there was plenty of blood n guts, but Aaron narrowed the focus, devoting entire issues to events taking place over relatively short periods of time (panel after panel of bloody hand-to-hand combat; an extended sequence with convicts unable to work up the nerve to attack the wounded, bedridden Castle), curtailing Frank’s international peregrinations, and bringing in versions of Marvel U characters like The Kingpin, Bullseye, and Elektra. The fact that he was telling the final Punisher story allowed Aaron to compensate for the addition of their more fanciful villainy by directly addressing the implications of what Ennis and other writers had been forced (by the ongoing nature of the character) to dance around: a character as firmly based in the Vietnam experience as Ennis’ Punisher would now be an old man, for whom the impossible wear, tear, and… well, punishment… of his vigilante lifestyle had to finally catch up with him.

And, last issue, it did. Anyone who feared that the finale of issue #21 would give way to some classic comic-book misdirection can rest easy (so to speak): Frank Castle is dead (at least in his MAX incarnation), and issue #22 consists of Nick Fury reflecting on the meaning, or lack of it, of The Punisher’s mission of mayhem. Of course, both Bullseye and the Kingpin had taunted Frank to acknowledge and accept the futility of his war on crime, and as Fury retraces Frank’s final battle, he reaches the same dour conclusion. It would be like Aaron to leave things on that bleak note, but he’s actually got something sneakier up his sleeve: at the end, just as Fury has pronounced the Punisher’s life work a failure, his attention is caught by TV newscasts showing hordes of “ordinary citizens,” who have been inspired by The Punisher to mask up and beat some gang members to death with wrenches and tire irons. It’s a wicked parody on the idea of the fallen hero’s ideals living on: what Frank Castle has evidently bequeathed to his world is not hope, but an ugly form of vigilantism, and that is the only thing that brings a smile to Nick Fury’s grizzled face, and warms his corrupted soul.

I’ve always thought that Steve Dillon (much as I love his artwork generally) was kind of an odd choice for the Punisher MAX series: he’s so closely associated with the pitch-black comedy of Ennis’ Marvel Knights version of the character that his exaggerated noses and death’s-head eyes sometimes seem to bring a winking, tongue-in-cheek wickedness that was at odds with the scripts. But heaven knows, no artist earned the chance to take the “last shot” at the Punisher more than Dillon has, and his work has been as vivid and disquieting as ever on this final run. And for anyone who feared that the loss of Tim Bradstreet’s covers would tamp down some of the visual appeal of the series, Dave Johnson’s work, though diametrically opposed to Bradstreet’s in style, never failed to make his issues of Punisher MAX look like a comic you just had to read.

I don’t know if this conclusion also signals a folding of the MAX tent altogether, but I’d have no problem with that, really; Marvel’s never put the marketing muscle behind the concept to make it work as its own line, and now that its first unequivocal success since Alias has finally wrapped up (after over a hundred issues, once you throw in all the miniseries), I’d say it’s time. And full credit to Aaron and Dillon: given the challenge of writing a coda worthy of Ennis’ epic, they’ve succeeded to a degree I’d not have expected.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

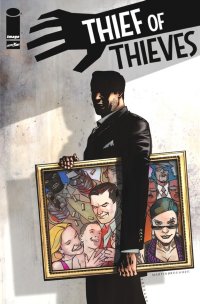

Thief of Thieves #1 (Image, $2.99)

Thief of Thieves #1 (Image, $2.99)

By D.S. Randlett

What makes a good first issue? Since getting back into comic books a few months ago and making an effort to seek out new, non-superhero series, this has been a question very much on my mind. Of all the bigger independent publishers, Image is probably the king of first issues. They are constantly debuting new series and taking chances on new concepts, which is to be applauded. But with many of these series, I don’t feel like I can properly give a solid recommendation or warning until four or five issues in. Take Pigs, for example, which is worth seeking out, but I still don’t think that it’s really expressed what its stakes are, and why the story that’s unfolding really matters for the characters that populate it.

Thief of Thieves is a skillfully written and drawn book. There’s no denying either of those. It just looks great, with the art of Shawn Martinbrough echoing the work of Sean Philips’ noir work with Ed Brubaker, combined with the playful sensibilities of someone like perennial cover artist Dave Johnson. Like the art, the dialogue from co-writers Robert Kirkman and Nick Spencer pops. These characters are fun people to spend twenty two pages with, and there are hints that there is more going on under the surface with them than the reader really suspects. There are some interesting pieces on the board, surely.

But that’s kind of the problem: there are hints. There are hints of a story, hints of character. This is essentially a conman/mystery series, so I get that the creative team wants to hold some stuff back, but there just aren’t any stakes at this point that really make the story connect. What we do get in this issue is basically an amusing heist and introduction to the principle characters, but it all builds to a cliffhanger that feels unearned, a decision that has no basis for the reader unless he or she read the solicitation beforehand.

Thief of Thieves is a very well made comic book, and looking forward I can see a lot of potential. But that’s part of the problem. Make me care right now. I can see this becoming a great series, but you might want to wait for a few more issues before really jumping in.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

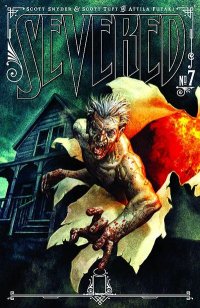

Severed #7 (of 7) (Image, $2.99)

by Graig Kent

Seven months ago I gave the first issue of Severed a 4-Starro (or whatever that symbol is*) review, noting that, as a reader, I had to adjust how I was reading to aptly appreciate the book. With the sheer amount of comics I consume in a month (along with TV and movies and music and podcasts and… jeez how do I have any time to work and raise a family?) I don’t always give everything the time it might deserve. With Severed, the realization was not every story is so easily consumable, and certainly not every story is so disposable. With each subsequent issue of Severed, I found myself putting it closer to the top (if not on top) of the pile of that week’s comics, in part so I could see what happened next — as the story made for an exceptionally enticing serial — but also because the further up on my pile a book is, the more patiently I read it.

I still stand by that 4-star rating for the first issue, but each issue since has been, hands down, a 5-star product. For the past 5 months, shipping on-schedule no less, this has been easily the most overlooked book on the stand. Severed is a horror title, but it’s old-school, slow-burn, atmospheric, creepy horror. Yes, it’s not very modern, with a lack of blood and gore and anything resembling the usual horror or torture-porn conventions, but its mid-1910’s setting should be an easy tip off that it’s not supposed to be.

In the beginning, the protagonist, Jack Garron, runs away from home, riding the rails and traveling the countryside on a journey to meet up with his estranged father. Ill equipped to handle life on his own, he meets Sam, another transient teen (also a girl posing as a boy) who takes him under his wing. Meanwhile, a traveling phonograph salesman, Alan Fisher, weathered and weary-looking, had just deceptively taken an orphan as his ward, quickly revealing that he’s not as he seems, but rather a sharp-toothed cannibal. Having fed, his path crosses with Jack and Sam, and his friendly, well-crafted exterior, fools the pair for a time. But, as we’re aware from the prologue of the first issue, set decades in the future, Jack loses an arm, and this final issue is the climax to the expertly teased build-up.

I have to say that I wasn’t looking forward to this final issue, only because it is the end to a story that was exciting me month after month. Writers Scott Snyder and Scott Tuft set out to write a moodier horror story than what we typically see today, but one that still would entice the Fangoria crowd, and they’d succeeded beautifully, really transporting the reader to a time where electricity and automobiles were still relatively new concepts, and trust was far more easily earned. Their artist, Attila Futaki captures the desolateness, the unconnected-ness, if you will, of the era so beautifully, not to mention the style and aesthetic of the time, which are realized with rich details and colored with a sepia-infused filter. I wanted more long before it finished.

Yet, I also have to say that I’m not as enthused by the finale as I was by the rest of the series. It’s not a weak ending at all, but I felt moments didn’t ring so true, particularly involving a just-amputated, single-armed Jack taking on Alan Fisher and then fleeing in a car. Adrenaline seems the simple explanation, and I’m sure one just needs to look at Aron Ralston (he of 127 Hours) to see what someone is capable of for survival, but the lengths Jack actually goes to and what he should actually be capable of seem dissonant. As well, there’s a bit more exposition in the opening pages than I felt necessary, as I think in horror, the less that’s explained outright about the machinations of its monster, the better off that monster is. But, this issue also reveals exactly how much of a monster Alan Fisher is (in sympatico, Futaki’s brilliant covers on the series had, for the past six issues, found small tears in an otherwise tranquil portait of the era’s landscapes with a sinister hand or eye or mouth lingering behind, whereas this issue reveals in full the monster that was hiding behind all along). The slasher/torture conventions may not be at play as expected, but they are utilized in their own way in this final issue, and a new supernatural, very American creature is born.

This issue’s epilogue wraps back to an older Jack, where we left him from the prologue, hinting, in truest horror fashion, that perhaps this story isn’t as finished as we’d though. In the letter columns issues prior Snyder and Tuft made mention they have more Severed in their pocket, and this issue’s endgame certainly seems to allude to that. Whatever issues I have with the finale to the story, any disappointment I might have is made up with by the hope of more. While I wait, I can spend even more time getting lost in this creepy little world.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Fantastic Four: Season One (Marvel, $24.99)

Fantastic Four: Season One (Marvel, $24.99)

By Jeb D.

For the past few years, the Big 2 have worked their little tails off to try and persuade the millions of fans of their superhero movies to start reading the adventures in four-color (or do I mean 256-color? 64-million?) form. I don’t know that they have much to show for it (DC’s own figures on their recent relaunch indicate that a whopping 5% of “New 52” buyers are new comics readers), but they do keep trying.

Marvel has tended to focus their efforts on finding alternate, standalone retail channels, with the Ultimate Universe the most obvious example: what was supposed to be a line that would establish itself at places like Toys R Us and Target turned out to do most of its business in the same comic shops that were selling the regular Marvel U stuff (how much this might have cannibalized sales of existing Marvel titles is something they’ve always downplayed). And the “Season One” initiative is intended to give bookstore customers a new “starting point” for Marvel’s flagship titles. Commercially, it feels a bit neither-fish-nor-fowl: either they expect these brand-new customers to pay hardcover prices to establish some ongoing relationship with these characters (unlikely at $25 a pop), or they somehow think this will get those folks into the regular Wednesday comic-buying habit (even less likely). What will probably happen is that whatever sales it generates will mostly go to established fans of the franchise, and the circle-jerk will continue.

But that’s Dan Buckley’s problem, not mine. So let’s turn from the business model to the book itself: is the darn thing any good? Is it worth $25? Allow me to answer with a resounding “Kind of” and “Hell no… well, not to you, anyway.”

Playwright Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa has what I believe to be a unique distinction: to my knowledge, he’s the only writer who ever got his very first comics gig on Marvel’s flagship superteam. In 2004, newly recruited to comics, he found himself in the middle of one of Marvel’s semi-regular “fanboys versus pencil-pushers” kerfuffles, when he was announced as the new Fantastic Four writer to take over from Mark Waid, then in the midst of a popular run (with the late Mike Wieringo) on the book. Eventually, after the smoke cleared, Aguirre-Sacasa’s version of the team, with artists Steve McNiven, and then Jim Muniz, would run for thirty issues in a parallel Marvel Knights monthly, simply entitled 4**, and it was easy to see what Marvel thought Aguirre-Sacasa would bring to the FF. MK4 was a stark contrast to the colorful old-school tales that Waid and Wieringo were spinning; where cheerful retcon was the order of the day for W & W (I personally disliked the idea that the Yancy Street Gang’s pranks on Ben were actually all Johnny’s doing), MK4 seemed interested in looking more deeply into the team’s dynamic (what if the FF went bankrupt? what impact has Reed’s messing with time and space travel had on the world of “ordinary” humans?), and their relationships with familiar characters like the Puppet Master and The Inhumans. Not every storyline worked perfectly (the monster-in-the-woods bit was an interesting failure), but it made a nice counterpoint to Waid’s take.

Given this, I can see why Marvel thought Aguirre-Sacasa was the writer to launch the first of this vaguely misbegotten series of “new” origin stories. In some ways, though, it strikes me that Aguirre-Sacasa was actually the wrong guy for the job (or, more to the point, this job was a waste of his skills): his strength was taking the team into unusual places, not finding ways to dress up places they’d already been.

Structurally, the storyline here is a retelling of the first few issues of the original Fantastic Four comic: the spaceflight, the powers, and encounters with the Mole Man and Sub-Mariner. Aguirre-Sacasa adds a few twists here and there (among other things, borrowing the character of Dr. Alyssa Moy from Chris Claremont, to take some of the exposition off Reed’s shoulders). Mostly, though, he just tries to shoehorn the crude wildness of the early Lee-Kirby issues into something that won’t ring completely false for 21st century audiences. He knows the characters well enough that he doesn’t really put a foot wrong with their personalities, he only throws in a few grating modern references (Mad Men, J.J. Abrams, etc., while mostly ignoring things like iPads or the Internet), and he takes in stride the demand for up-to-date refinements: Sue starts out as anything but the mopey ditz that Lee wrote, and she almost immediately becomes “the strongest member of the team.” But he’s a playwright first and foremost, and his comics have always tended toward the talky: by the end of this book, we’ve had more self-analysis from Reed than any ten years of the regular comic would produce, bogging things down. There’s a bit of action here and there (we get the familiar monster from issue #1, with a twist, and Namor is happy to throw down as soon as he’s introduced), but because it’s being compressed in between so many dialog-heavy segments, it feels almost ludicrously sudden when it takes place; the segment where Ben is made human again, then allows himself to change back to The Thing to save the day, comes off even more abruptly nonsensical than it was in the FF movie—or the original comic. And despite the story’s acknowledgement of the WW2-era Marvel characters, it feels a bit “off” that the birth of the FF takes place in a Marvel Universe that is already fully up to speed on the concept of superheroing (we even get one panel of Dr. Doom watching his old college pal in the tream’s first TV appearance with barely a hint of surprise).

Artist David Marquez’s clean, angular style is more than a bit reminiscent of the look of MK4; he’s consistent with his character work, and brings a nice perspective to his monster design. I don’t know that Johnny’s free-spirit character is enhanced any by the washboard abs, but it may be worth noting that between him and Namor there’s more beefcake than cheesecake in this comic.

I guess it’s sorta commendable that Marvel isn’t attempting to re-write the team’s origin in any significant way… but you could also say that it’s sorta greedy and opportunistic to ask readers to pony up $25 and not, in fact, give them some kind of “Secret Origin” to chew on. By the way, your $25 also gets you a reprint of Jonathan Hickman’s first Fantastic Four issue, which is supposed to bring the new reader up to date, but which also significantly reduces the “new-pages-per-dollar” value for the established fan.

In the end, this book succeeds in its principal artistic goal: it tells a reasonably faithful version of the origin of the Fantastic Four, in visual and verbal language that is more comfortable for 21st century audiences. The question is, how much is that worth? Bear in mind that if you’re reading this column, you are, by definition, NOT the newbie audience this is supposed to be for, but it’s your 25 clams. Either way, I read it over a $1.80 cup of coffee at the store, so I’m $23.19 to the good on this.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

*The little rating thing has always looked sort of like a Baby Cthulu to me.

**My favorite quote that I’ve read this week comes from an Amazon review of one of the MK4 trade collections: “Marvel needs to limit its apocalypses to no more than one per year.”