McG is like a salesman, and his product is the New McG. “I selected this picture because I want to grow as a filmmaker,” he says at the New York City press junket for We Are Marshall. Later he says, “I want to continue to grow. Before Clint could do Mystic River he had to do Every Which Way But Loose. Sean Penn was Spiccoli before he became a credible actor, and Ron Howard was Opie, for goodness sakes. I realize it’s going to take some time for me to make this course correction and this sea change, but I hope this film is a step in the right direction as I try to grow and become a better and better storyteller.” He wants to “learn from guys like Mark Romanek, Michel Gondry, Spike Jonez, some of my contemporaries, and some of the guys who have been around a lot longer than that and grow as a patient, resolved storyteller.”

McG is like a salesman, and his product is the New McG. “I selected this picture because I want to grow as a filmmaker,” he says at the New York City press junket for We Are Marshall. Later he says, “I want to continue to grow. Before Clint could do Mystic River he had to do Every Which Way But Loose. Sean Penn was Spiccoli before he became a credible actor, and Ron Howard was Opie, for goodness sakes. I realize it’s going to take some time for me to make this course correction and this sea change, but I hope this film is a step in the right direction as I try to grow and become a better and better storyteller.” He wants to “learn from guys like Mark Romanek, Michel Gondry, Spike Jonez, some of my contemporaries, and some of the guys who have been around a lot longer than that and grow as a patient, resolved storyteller.”

“I’m just trying to improve,” he says. “I know in my heart that I am doing the best I can to show growth as an artist and be taken seriously as a filmmaker.” McG stays on that message, just like a good salesman or politician. I’m not saying that in a derogatory way – I’ve done door to door sales and run my own sales office, so I know how hard selling is, and what skills are needed for it. McG has those skills.

McG is a hard guy to dislike. He’s tall but not imposing, and he’s quick to create a feeling of intimacy. During my one on one with him at the We Are Marshall junket, McG introduced me to Matthew McConaughey, saying I was “a good guy.” Later he told me I was “a very literate film enthusiast, clearly.” I was impressed with that because a press junket isn’t the kind of place you find a lot of literate film enthusiasts, so it would be a compliment lost on most of the people there. McG was able to size me up very quickly and figure out what would work best on me. That’s a great sales skill.

He’s also a marathon type of guy – I spoke to him twice at the junket, once at a roundtable in the morning and almost six hours later in a one on one. During the course of the day he must have answered the same questions again and again hundreds of times, but he never lost his energy. By the time of my one on one – his last for the day – he was a little subdued but still able to pour out torrents of words. I would ask him a question about his use of music in the film and get almost 800 words out of him, ranging from having a black guy singing Black Sabbath’s Paranoid to how he’s in the zone as a filmmaker and then – bang! – back to the message. “Under no circumstances am I rejecting my past. I’m just trying to grow. I love ET, but I certainly love Schindler’s List. Schindler’s List is a very important film and a stunning cinematic achievement. I’m no Steven freak, I don’t like everything he does. But I certainly like Jaws, and I certainly like Schindler’s List. Those are 180 degrees from each other and I don’t think he would ever downplay what he had done earlier. Not that I ever would include myself in the same sentence as [him]. But I’m just trying to improve.”

The Old McG grew up in Orange County, where he was always McG. “I do have a stupid name, but my parents gave it to me and I can’t go back to my name,” he says. “It’s stunning how much grief that’s caused me. It’s unfortunate and I wish that wasn’t my name. [But] it’s who I am. It’s just unfortunately who I am. I am Joseph McGinty Nichol, and my grandpa was Joe and my uncle was Joe. We were poor. The whole family was around with great regularity and we had Grandpa Joe and Uncle Joe and they didn’t want to call this little kid Joe, so they called me McG, short for McGinty, and that’s been my name ever since.”

McG hung out with Gwen Stefani and Sugar Ray’s Mark McGrath when they were nobodies. He didn’t start as a filmmaker – he was a photographer who took pictures of the bands he hung with, and he produced records for them, wrote songs with them. “It was all one thing,” he says. “None of it was compartmentalized jobs.” But soon the roles crystallized more, as McG started making videos for the bands, and they started getting record deals from them. That led McG to Gap commercials – “I helped the Gap change who they were when they used to have a bad 70s image” – and then found his way into features with Charlie’s Angels.

It’s not the usual story you hear from filmmakers. Most often they tell you about how they were in love with movies as a kid and how they aimed their whole lives at getting a film made. Not McG. “When I got started I wanted to be Rick Rubin, I wanted to be in the record industry. I was inspired by Rick, who started his label, Def Jam, in his dorm room in NYU.” McG seems to have stumbled into it, but he doesn’t see much of a line between where he started out and where he is now. “I’m as likely to listen to music for inspiration in film as I am to watch film for inspiration in music, and I create very little separation,” he says.

And he’s not ashamed of where he’s been, and especially not of the Charlie’s Angels films, the only successful female action franchise in history. “I’m extremely proud of those pictures,” he says when asked if Marshall is an attempt to distance himself from his previous work. “Here’s what I’m most proud of – [they’re their] own animal. People certainly have the right to say, ‘I fucking hate that.’ OK, that’s fair. But [they’re] not derivative. It’s not the same as this or the same as that. It’s its own stand alone tone, its own stand alone pop song. And maybe that’s not for everybody, but as a filmmaker, to create something that stands alone – I’m very proud of that.”

That’s the history of the Old McG. So where does the New McG come from? “I had walked a very difficult and embarrassing path with Warner Bros in regard to the Superman experience,” he says, and it’s hard not to see some of the impetus for change coming from that. McG was set to direct, but his notorious fear of flying kept him from getting on a plane down to Australia to actually make the film. He acknowledges that not many fans lost sleep about that: "I don’t think there was a voice on the planet that was excited about my version of that picture." But there’s something else behind the New McG, and it might be as prosaic as peer pressure. “I had been sitting in the Creative Rights Council at the DGA; I was asked to join by Steven Soderbergh, a hero of mine,” he says. “I sit next to Peter Weir, I sit next to Michael Mann, I sit across from David Fincher, and I hold these people in reverence. They challenged me, they said, ‘What are you going to do to show growth?’”

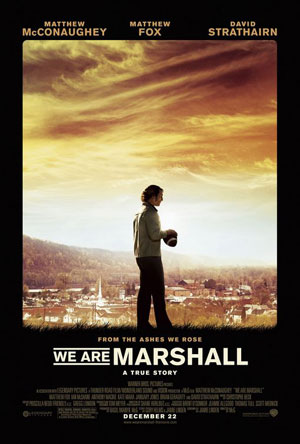

The answer is We Are Marshall, an un-football football movie (“I always half-joked that this is a football movie like Ordinary People is a swimming movie.”). Based on the true story of Marshall University and the surrounding community trying to come to grips with and get past a tragic plane crash that killed the whole football team, the coaching staff and many prominent residents, We Are Marshall isn’t a pop culture soaked explosion of eye candy, it’s an old-fashioned weepie. And it offered him a chance to face the big fear that kept him from his own superhero franchise. “I selected this picture and I wanted to shoot it in an architectural capacity, very methodical capacity. I wanted to show growth. And most importantly I wanted face the abyss of my own fear. I knew this was a film about a plane crash, and it would require a lot of flying on my behalf and I would have to fly into the airport where the crash took place. The first thing I did when I got into Tri-State Airport was went to where the crash took place and I sat there by myself for hours, and tried to search my heart to see if I had the courage and if I was the right guy to do it justice.”

I’m convinced that McG isn’t just staying on message to deliver interesting copy. He means what he says, but what does what he’s saying mean? One of the most interesting things that McG said to me during our one on one was about his music scene: “[O]ur whole Orange County thing was reactionary to what was going on in Seattle.” He’s talking about the whole grunge/Nirvana/Pearl Jam scene, which was trying to bring emotion and depth back to music, getting it away from the hair metal cock and booze songs. The OC bands definitely reacted to that, making airy, light and ultimately disposable pop songs. But it’s another example of how McG is coming from a completely different direction than many other filmmakers – he never made experimental student films, and even if given a chance, he probably wouldn’t have wanted to.

The “Seattle scene” equated success with selling out – it was one of the things Kurt Cobain was never able to reconcile in his own life. Today Mark McGrath hosts the tabloid TV show Extra; it’s hard to imagine Eddie Vedder doing that. But there’s something else that McG said to me that I think delineates the difference in attitude: “I’m just really excited about continuing to make films and continuing to grow,” he says, ever on message. “There’s a fundamental confidence in knowing how to do something – if you were a shoemaker and you were like, I just know how to make shoes right now, man. People can say they hate the shoes, they’re entitled to that, but son of a bitch, I know how to make shoes, man.”

He’s got a head of steam built up now, and he goes on, using some interesting words: “And I’m so comfortable with developing the scripts, with interfacing with the actors, with talking to the crew, setting up shots with the DP, talking with the gaffer, working with the grips, talking to the production designers, the costume designers, interfacing with the studio – I’m so comfortable and so familiar with those aspects of filmmaking. It’s wonderful in life when you can immerse yourself in something.”

“Interfacing with the actors,” is a very telling word choice. It’s corporate-speak, and not the kind of thing you could ever imagine Martin Scorsese saying. But McG and Scorsese are coming from totally different worlds – Scorsese is happy to make his films for small budgets just so he can get his vision out there. McG comes from a background where financial success isn’t just the goal, it’s seen as going hand in hand with artistic success. “I’m not doing it for you and I to watch it at your house, you know what I mean?” he says. “I’m doing it so that people can have the communal experience in the theater and enjoy it.”

Back to the pilgrimage to Tri-State Airport, where McG contemplated whether he was the right guy to do the Marshall story justice. Was he? He thinks so. “I think it would be very difficult to see this film and say it’s a bad film,” he says. “You may like it a lot, you may think it’s alright, I can see someone saying it’s a little formulaic, perhaps a little melodramatic. But it’s just not a bad film. If you look at We Are Marshall and think it’s a bad film, you’ve got a strange agenda. You’re not being very forthcoming with an analysis of the picture. A lot of people – and I know this because I’ve sat in rooms with 500, 600 people in them – I’ve heard the audible sobbing. I’ve heard the audible laughter. After 13, 17 screenings you start to go, ‘OK, I’ve got the data. People are emoting with this picture.’ There are a lot of my heroes who never made me cry. Alfred Hitchcock never made me cry. I worship, I revere Alfred Hitchcock – but he never made me cry. As a filmmaker, if I can go to a place where I’ve made Charlie’s Angels and now I made a film that makes people cry? I’m creating a great deal of separation between many, may other directors, and that’s tremendous source of pride for me. Now if somebody acts up on the internet and says, ‘McG’s a fucking asshole and he sucks and hack this that and the other.’ Well, perhaps they’re right, but perhaps they haven’t looked closely enough.”