There are a lot of galling things in Blood Diamond, the new Africa in crisis movie, but perhaps the most galling is the way the film insists on making a white guy the lead when the whole thing is the black guy’s story. It’s not even a question – if the film has been set in Europe or the US or a futuristic moon colony, the guy who is desperately searching for his family would be the lead. But because this is Africa, and the guy is black, he becomes the sidekick to a Hollywood star, Mister Leonardo DiCaprio.

There are a lot of galling things in Blood Diamond, the new Africa in crisis movie, but perhaps the most galling is the way the film insists on making a white guy the lead when the whole thing is the black guy’s story. It’s not even a question – if the film has been set in Europe or the US or a futuristic moon colony, the guy who is desperately searching for his family would be the lead. But because this is Africa, and the guy is black, he becomes the sidekick to a Hollywood star, Mister Leonardo DiCaprio.

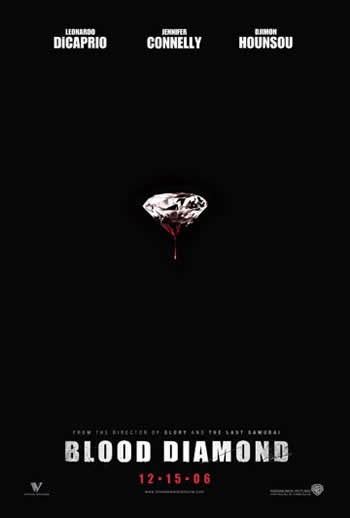

I actually think that Leonardo DiCaprio and director Ed Zwick are a good combination, at least for each other. Leo’s outgrown his teenybopper days and is like, serious, man. He’s into issues. And dark characters. Ed Zwick, meanwhile, is very much all about examining the problems facing the world’s beleaguered minorities and oppressed groups as seen through the eyes of the white people who help them. This time they come together to reveal the terrible costs of conflict diamonds – illegally sold gems that fund regional civil wars in Africa.

Blood Diamond opens with the man who should be the lead: Djimon Hounsou, who lives in Sierra Leone when a brutal war breaks out. He is captured by the rebel forces and made to labor in their diamond pits, while his wife and children become refugees. While working in the pits, Hounsou discovers a diamond of incredible size and stupidly decides to try and steal it. It’s an exceptionally dumb decision because he had just seen another guy take a bullet in the heart for the same crime. He tries to hide the diamond, but gets caught by a guard and is about to be killed when – bang! The army shows up. A lot of stuff like that happens in Blood Diamond – last minute arrivals save the day and thousands of rounds of ammunition are shot in the film but none of our heroes get hit. Everybody around them takes bullets – lesson number one from Blood Diamond is never travel in a land vehicle with Leonardo DiCaprio, as you’re quite likely to be shot – but they remain unscathed. Until dramatically necessary.

Anyway, Hounsou ends up captured by the army, who thinks he’s a rebel. He goes to jail and there he comes across DiCaprio, a Rhodesian smuggler and mercenary who just got picked up trying to bring conflict diamonds across the border to sell to the big diamond companies. While in prison Leo hears word of this big diamond and he decides to use Djimon to get it. He promises the man that he’ll help him find his family – the wife is in a refugee camp while the son has fallen into the ranks of the rebel’s child soldiers – but it’s really about making one last score.

One last score. In how many movie have you seen that? But what about this one – the cold-hearted merc who slowly comes to respect the man he’s using and stops looking out just for himself. Yeah, that’s here too. It’s one of the many boring tropes and clichés Zwick and his screenwriter Charles Leavitt stuff into the film, which by the end is bursting like a Hot Pocket you microwaved too long. If it had just been Leo and Djimon I maybe wouldn’t have minded it all – an updating of The Defiant Ones in post-colonial Africa. But the focus groups like romance, so Jennifer Connelly shows up as a very, very sensitive journalist looking to bring the horrors of the conflict diamond trade to the American people in her badly written (judging by what little bit we hear) news stories. She’s also there to deliver facts and figures to us, explaining why your diamond engagement ring cost a young man his arms.

She’s almost utterly extraneous in the film (besides serving to give us some Jennifer Connnelly to look at, never a bad thing), except to make googoo eyes with Leo and to drag his life story out of him in a scene that so undermines his character as to ruin the performance in whole. It’s hard to buy Leo as a hard-bitten military man – he looks much more like he should be putting daisies in gun barrels – but through sheer force of will DiCaprio had dragged me to a place where I could at least accept it. Then, in one weepy scene, it’s all thrown away. The scene is presented as a seduction sequence, but the seduction is never consummated onscreen, and later body language makes me wonder if we’re supposed to think it was consummated at all. Which is a big problem – I would buy Leo’s character using his tragic past to bed a woman; I don’t buy him crying about his tragic past to some girl reporter.

Then there’s Djimon. It’s interesting to watch him try very, very hard to make something out of his role. He seems to know that his story should be the center of the piece, not the redemption of a skeevy white guy, and he brings down a lot of emotion into every scene. A lot of emotion. Too much emotion. Again and again his character seems to just flip out, making very, very poor decisions. And this happens throughout the film. By the end of the movie you want the guy to wise up, to realize that there are ways to get his family back without just walking into a heavily armed camp of trigger-happy child soldiers and grabbing kids.

There’s stuff in here that works. When Djimon’s son gets inducted into the children’s army we see how the kids are trained and controlled and it’s fascinating; you imagine Zwick getting mad because this would make a good movie on its own but he couldn’t figure out how to get Dakota Fanning in there. He creates a believable, and often terrifying, Africa, and the movie doesn’t pull any punches with violence (inflicted on Africans) – we don’t just hear about kids losing their arms, we see it.

But the elements that work are crowded out by the Hollywood elements that don’t, and there tends to be more of that. Blood Diamond is like buckshot aimed at the movie screen – there’s so much going on here, so many different kinds of stories all smashed into two plus hours of running time, that the best stuff is often fleeting. Blood Diamond is nowhere near as terrible or as frustrating as The Last Samurai, which is probably because DiCaprio doesn’t make unreasonable demands on the story to make himself seem more heroic (you get the impression he would have liked Zwick to give his character herpes or something, just to rough him up), but it’s still nothing more than chicken soup for international humanitarian crises, an opportunity for Hollywood types to decry the bloody gem trade while reaching for a little Oscar gold.